专业丛书

U.S. Trust and Estate Planning 美國信託規劃實務(英文部分)

Chapter 1 Introduction to Cross-Border Estate Planning

Estate planning is the process of anticipating and arranging for the management and disposal of a person’s assets during the person’s life in preparation for a person’s future incapacity or death. While on its face, this may come off as simple, many individuals struggle with estate planning for a variety of reasons. This is especially true for those who have accumulated substantial wealth, referred to in this book as Wealth Creators.

Estate planning is the process of anticipating and arranging for the management and disposal of a person’s assets during the person’s life in preparation for a person’s future incapacity or death. While on its face, this may come off as simple, many individuals struggle with estate planning for a variety of reasons. This is especially true for those who have accumulated substantial wealth, referred to in this book as Wealth Creators.

For families based in multiple jurisdictions (commonly referred to as “Cross-Border Families”), estate planning may be even more arduous. This book aims to deliver workable solutions to Wealth Creators with family members and assets spread throughout several countries.

For non-U.S. persons with assets in the U.S. or descendants in the U.S. with U.S. citizenship or a U.S. green card, both the perceived cost of estate planning and the out-of-pocket legal fees and accounting expenses can be quite considerable. Moreover, depending on the Wealth Creator’s circumstances, the estate planning process can be unpredictable and may change over time. While each Wealth Creator’s approach to estate planning can and should be customized, we believe that knowledge of common structures used by others can serve as an important reference point.

For families based in multiple jurisdictions (commonly referred to as “Cross-Border Families”), estate planning may be even more arduous. This book aims to deliver workable solutions to Wealth Creators with family members and assets spread throughout several countries.

For non-U.S. persons with assets in the U.S. or descendants in the U.S. with U.S. citizenship or a U.S. green card, both the perceived cost of estate planning and the out-of-pocket legal fees and accounting expenses can be quite considerable. Moreover, depending on the Wealth Creator’s circumstances, the estate planning process can be unpredictable and may change over time. While each Wealth Creator’s approach to estate planning can and should be customized, we believe that knowledge of common structures used by others can serve as an important reference point.

Estate planning can and should be customized to each individual. That is why there is an entire industry devoted to wealth and estate planning. In our experience, Asia-based families frequently struggle with the same issues and have similar concerns when it comes to estate planning.

The most common theme is that Wealth Creators who generated substantial holdings in Asia have:

When completing such a change in identity (becoming a U.S. person) or transfer in assets (moving assets into the U.S.), Wealth Creators may not fully understand the legal and tax implications. To this end, Asian Wealth Creators often attempt to resolve these issues by hiring professionals both in the U.S. and in Greater China.

Some even retain the services of the Big Four Accounting Firms or large and established global law firms. In our experience, engagements with these advisors rarely yield effective and cost-efficient results. In practice, many of these firms often have a difficult time piecing together the relevant laws and regulations of multiple jurisdictions.

Further complicating the situation, practitioners at U.S.-based law firms and accounting firms focus exclusively on the area of estate planning that they specialize in, often deferring to other qualified professionals’ opinions when questions relating to other areas of estate planning arise. Unfortunately, this often results in the client receiving subpar outcomes, conflicting opinions and hefty fees. This is where this book could be useful. Every example illustrated this book has been understood and utilized by Wealth Creators who have similar questions and concerns.

The lead author of this book has settled numerous trusts for himself and his family. The majority of structures in this book have not only been created by the author, but they are also currently being updated, maintained, and improved upon to this day. Unlike most practitioners, who attest to their clients’ successes, the author actually utilizes this book’s very structures and can speak to their efficacy.

Wealth Creators should consider their succession strategy a core task and prioritize the creation of a sustainable plan to pass their assets on to their successors. While understanding key concepts can help, case studies are often the best way to truly understand estate planning and wealth succession. We include five illustrative case studies herein to help Wealth Creators with thinking about their trust planning.

The most common theme is that Wealth Creators who generated substantial holdings in Asia have:

1. immigrated to the U.S. themselves

2. had their spouse and / or descendants immigrate to the U.S.

3. invested in the U.S. by transferring all or a portion of their wealth from Asia.

When completing such a change in identity (becoming a U.S. person) or transfer in assets (moving assets into the U.S.), Wealth Creators may not fully understand the legal and tax implications. To this end, Asian Wealth Creators often attempt to resolve these issues by hiring professionals both in the U.S. and in Greater China.

Some even retain the services of the Big Four Accounting Firms or large and established global law firms. In our experience, engagements with these advisors rarely yield effective and cost-efficient results. In practice, many of these firms often have a difficult time piecing together the relevant laws and regulations of multiple jurisdictions.

Further complicating the situation, practitioners at U.S.-based law firms and accounting firms focus exclusively on the area of estate planning that they specialize in, often deferring to other qualified professionals’ opinions when questions relating to other areas of estate planning arise. Unfortunately, this often results in the client receiving subpar outcomes, conflicting opinions and hefty fees. This is where this book could be useful. Every example illustrated this book has been understood and utilized by Wealth Creators who have similar questions and concerns.

The lead author of this book has settled numerous trusts for himself and his family. The majority of structures in this book have not only been created by the author, but they are also currently being updated, maintained, and improved upon to this day. Unlike most practitioners, who attest to their clients’ successes, the author actually utilizes this book’s very structures and can speak to their efficacy.

Wealth Creators should consider their succession strategy a core task and prioritize the creation of a sustainable plan to pass their assets on to their successors. While understanding key concepts can help, case studies are often the best way to truly understand estate planning and wealth succession. We include five illustrative case studies herein to help Wealth Creators with thinking about their trust planning.

Background:

Mr. Fang is the Founder of a large restaurant group in Shanghai (a listed company) and just turned 65. Since Mr. Fang had a modest upbringing, he has always been extremely cautious financially. He primarily invests cash generated from his operating businesses in low-risk financial investments and real estate in China. Mr. Fang’s wife and children have lived in Los Angeles, CA for many years now, where he purchased a house under his wife’s name in 2015. Throughout the years, he has also gifted his wife various sums, which she has since invested in an LLC that holds equity investments in U.S. office buildings and shopping malls. While Mr. Fang’s wife and children have received U.S. green cards, Mr. Fang has not applied for immigration and is a non-U.S. person (a non-resident alien for U.S. tax purposes).

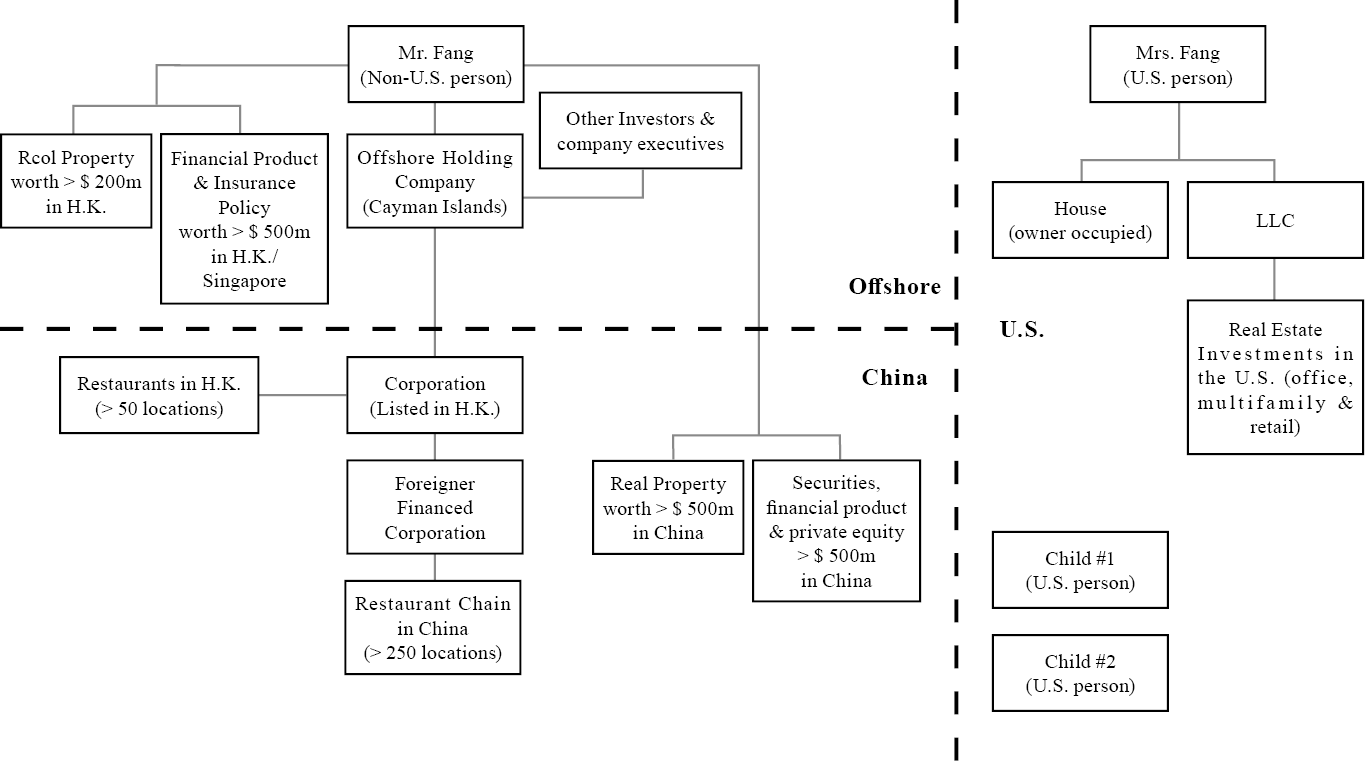

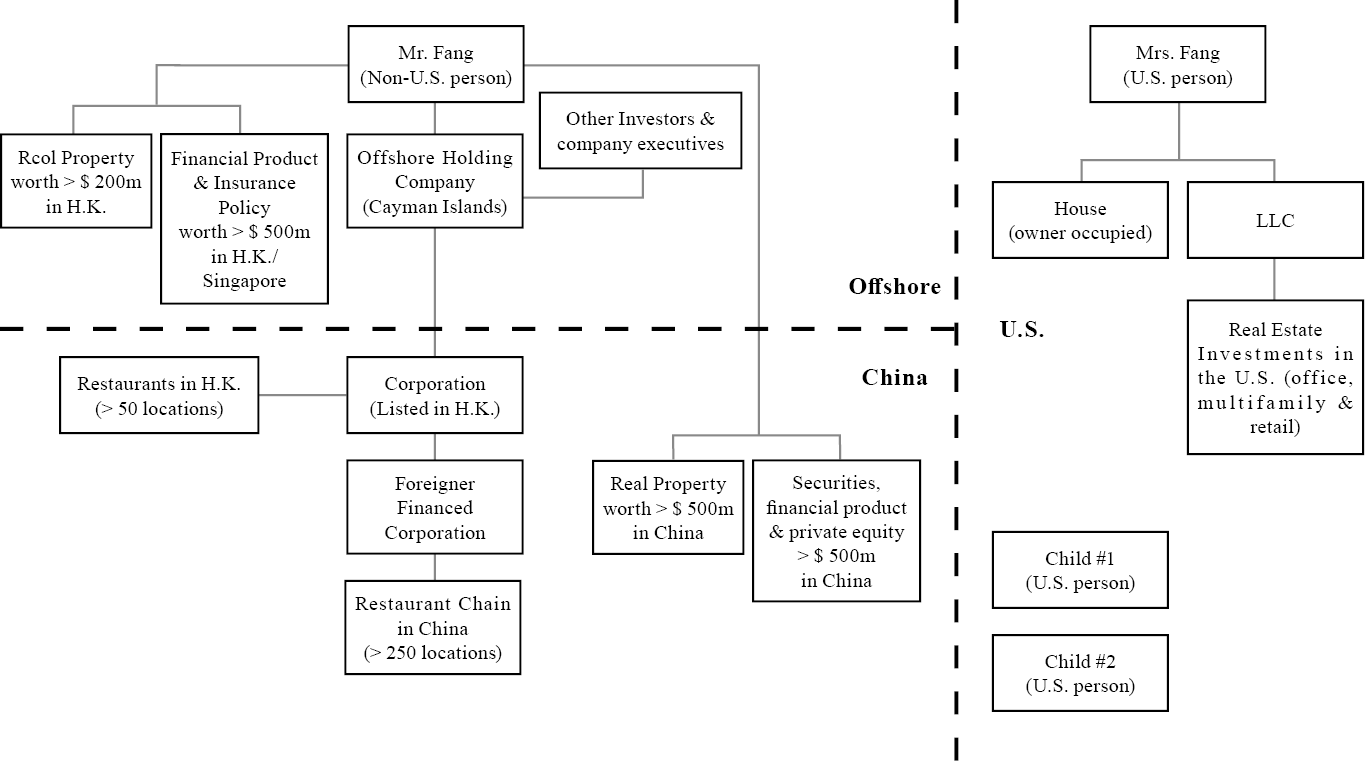

Below is a chart of Mr. Fang’s assets prior to estate planning:

Key Planning Points:

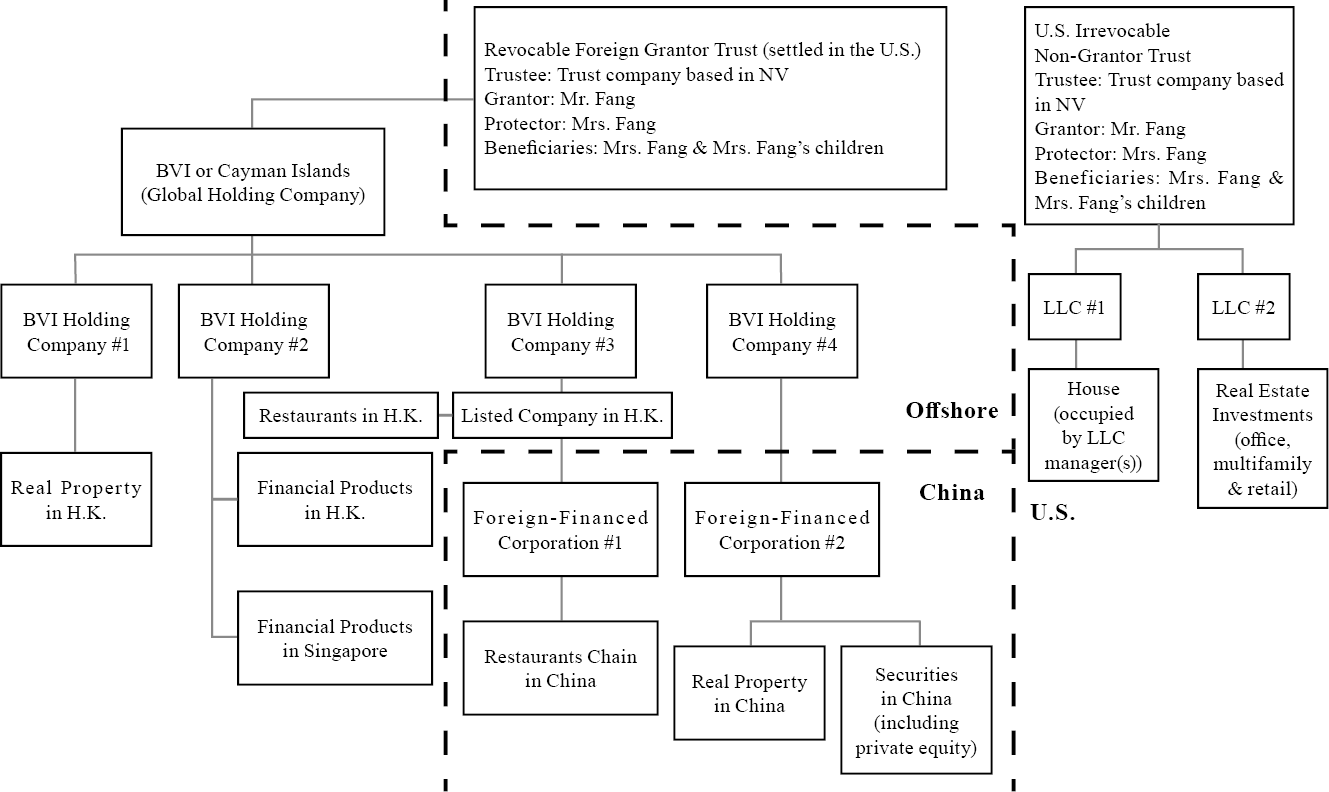

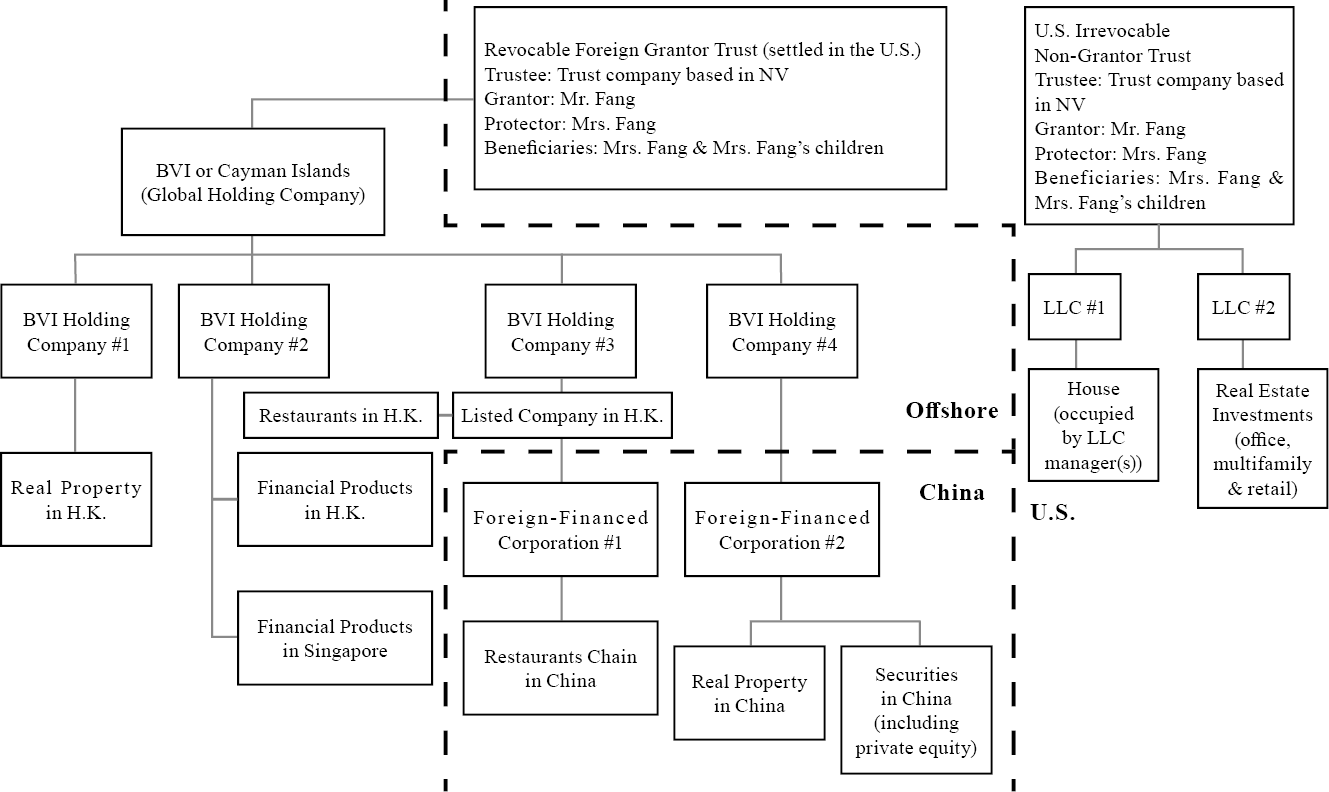

Below is a chart of Mr. Fang’s assets after estate planning:

Mr. Fang is the Founder of a large restaurant group in Shanghai (a listed company) and just turned 65. Since Mr. Fang had a modest upbringing, he has always been extremely cautious financially. He primarily invests cash generated from his operating businesses in low-risk financial investments and real estate in China. Mr. Fang’s wife and children have lived in Los Angeles, CA for many years now, where he purchased a house under his wife’s name in 2015. Throughout the years, he has also gifted his wife various sums, which she has since invested in an LLC that holds equity investments in U.S. office buildings and shopping malls. While Mr. Fang’s wife and children have received U.S. green cards, Mr. Fang has not applied for immigration and is a non-U.S. person (a non-resident alien for U.S. tax purposes).

Below is a chart of Mr. Fang’s assets prior to estate planning:

Key Planning Points:

1. Mr. Fang owns many assets in China. If China enacts an estate and transfer tax regime, a large proportion of Mr. Fang’s assets may be subject to taxation. To pay this tax, his descendants may have to sell off their families’ assets, potentially including shares of their listed company.

2. Since many of Mr. Fang’s family members have immigrated to the U.S. over the years, Mr. Fang wishes to transfer more of his assets into the U.S. If he wishes to apply for immigration to the U.S., he should consider transferring his assets prior to immigrating. An U.S. irrevocable trust can serve as an excellent vehicle to hold his funds currently held by offshore companies in Hong Kong or Singapore. Alternatively, a U.S. revocable trust prior to Mr. Fang’s death or immigration could serve as a vehicle for offshore companies that hold assets based in China or other operating companies.

3. When Mr. Fang makes gifts to his wife and children in the U.S., it is important to consider U.S. gift and estate tax implications of any such transfer. If Mrs. Fang holds enough assets in the U.S., it is likely that she will be liable for U.S. gift or estate tax if she receives additional assets from Mr. Fang over time. We recommend that Mr. Fang establish an irrevocable trust in the U.S. and transfer his assets into the trust. This would minimize the family’s exposure to a U.S. estate tax and facilitate a smoother transition of assets to future generations.

4. If members of the management team in China are awarded incentive compensation in the form of shares, they should receive shares of the Foreign-Financed Chinese Corporation. If members of the management team outside of China are awarded shares, they should receive shares of the BVI holding company.

5. Mr. Fang should consider restructuring his holdings in China. Due to tightening currency controls, moving assets out of China has become difficult. If the opportunity arises, Mr. Fang should consider transferring ownership of his China-based assets to various offshore companies to facilitate the transfer of assets to his descendants. With professional assistance, this can generally be done through direct transfers, pre-planned financing events and gifts.

Below is a chart of Mr. Fang’s assets after estate planning:

Background:

Mr. Huang, an entrepreneur based in China, owns several factories in Nanjing, Suzhou and Chengdu. His operations in China are held by W Corp., a Chinese holding company. W Corp. is owned by X Corp., a Hong Kong holding company that he holds. Over the years, he has transferred much of the profits from Chengdu to a Hong Kong bank account held by Y Corp., another wholly owned company. Periodically, he transfers funds from his Y Corp. bank account to another Hong Kong bank account held by Z Corp., a British Virgin Islands (BVI) company. Funds accumulated in Z Corp. are invested in various financial products and investments in both Hong Kong and Singapore.

While Mr. Huang is a Chinese citizen and does not have any plans of relocating to the U.S., his wife, daughter and sons are all based in the U.S. and have U.S. citizenship. Over the years, Mr. Huang has come to realize the need to formulate a plan that would allow him to effectively transition his assets to his descendants; however, he is unsure of how to proceed given the complexity of his structures.

Specifically, he had the following questions:

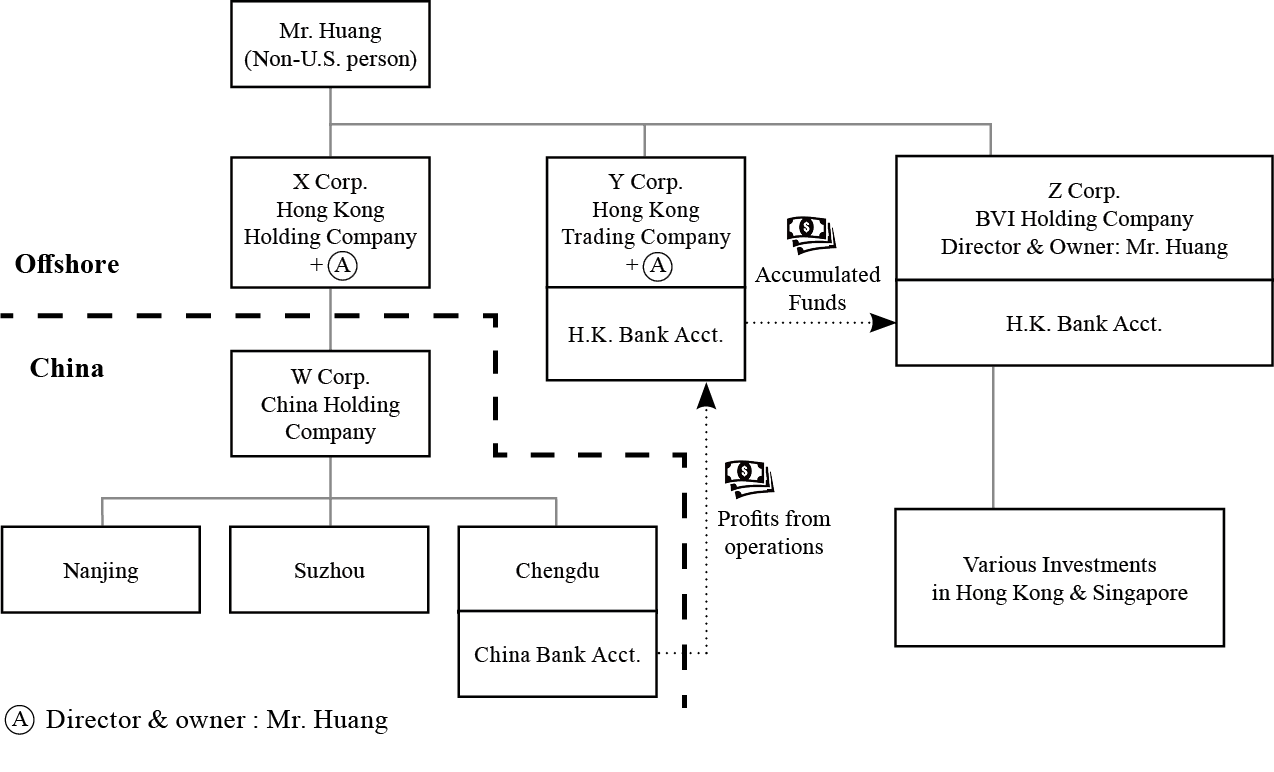

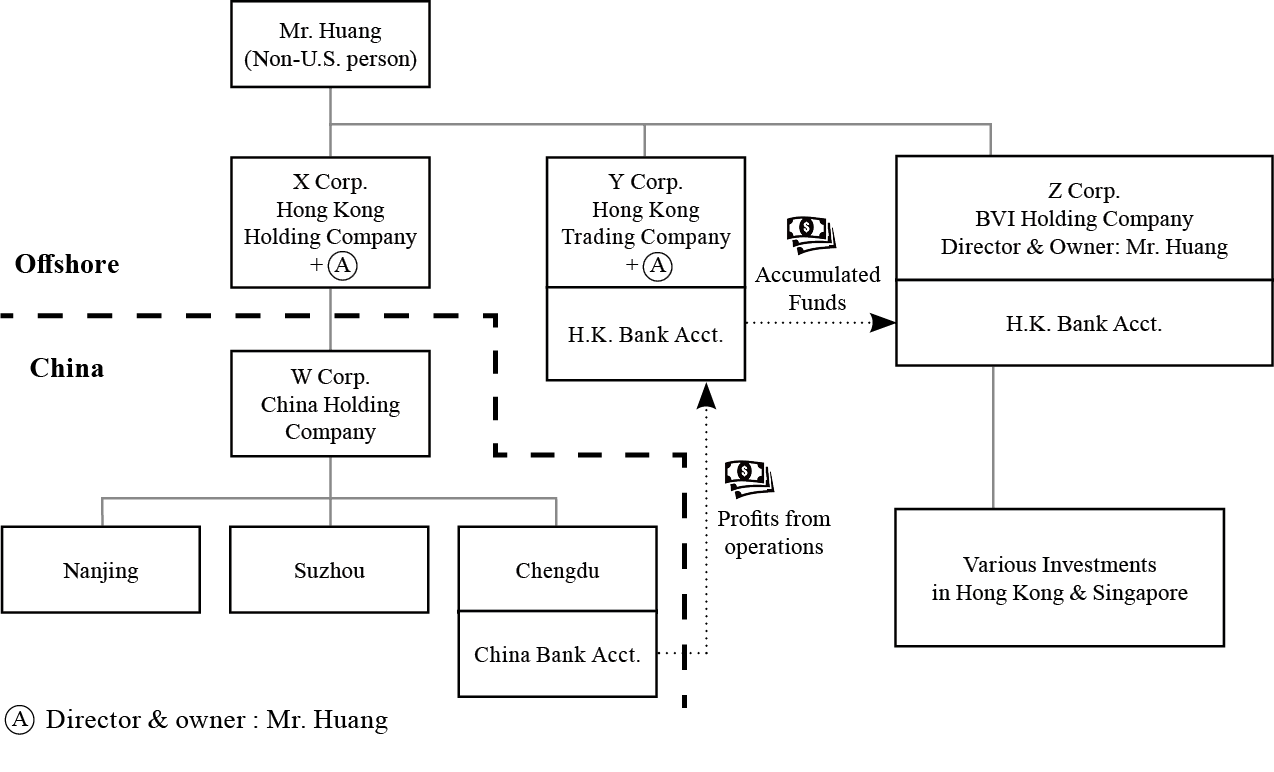

Below is a chart of Mr. Huang’s assets prior to estate planning:

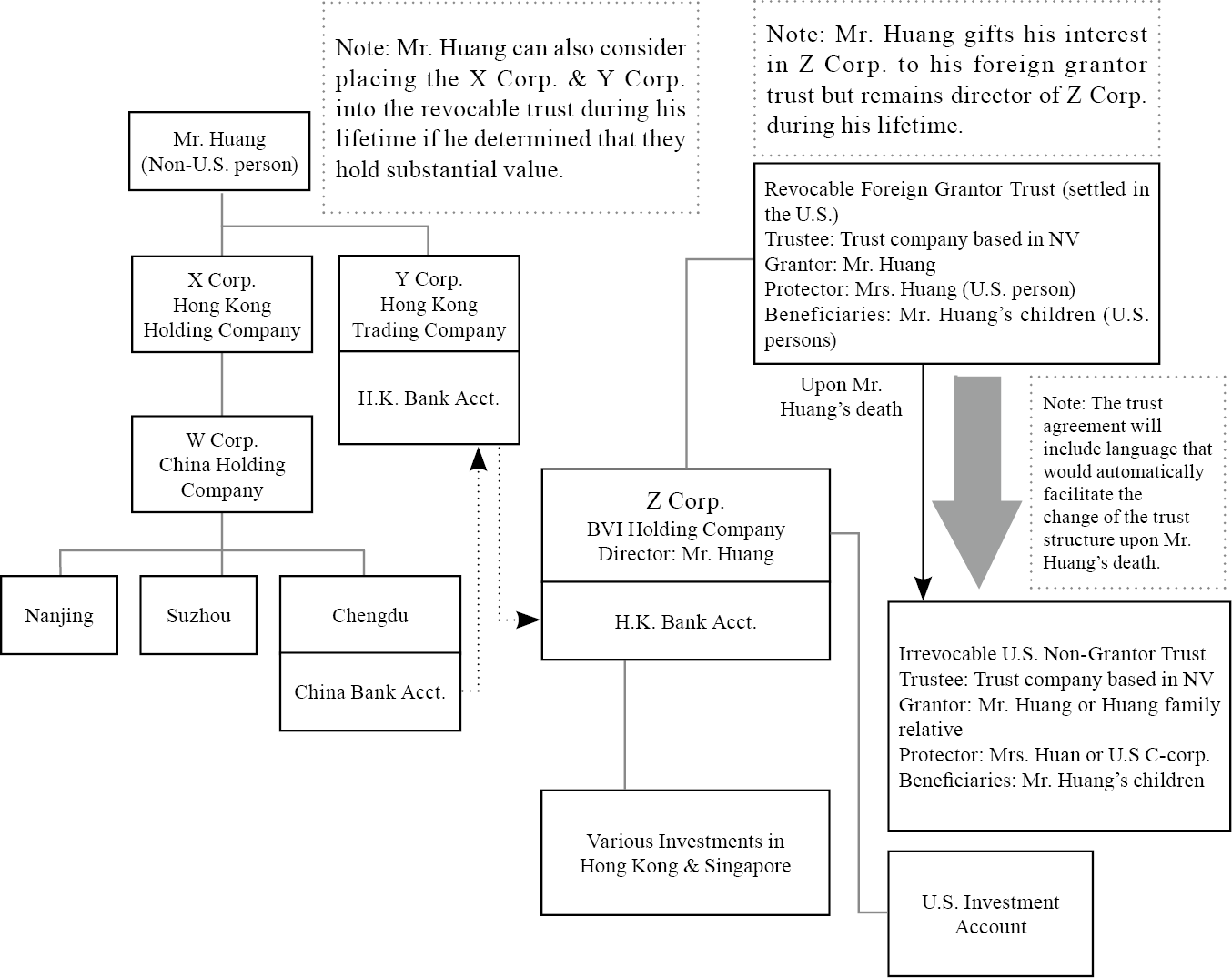

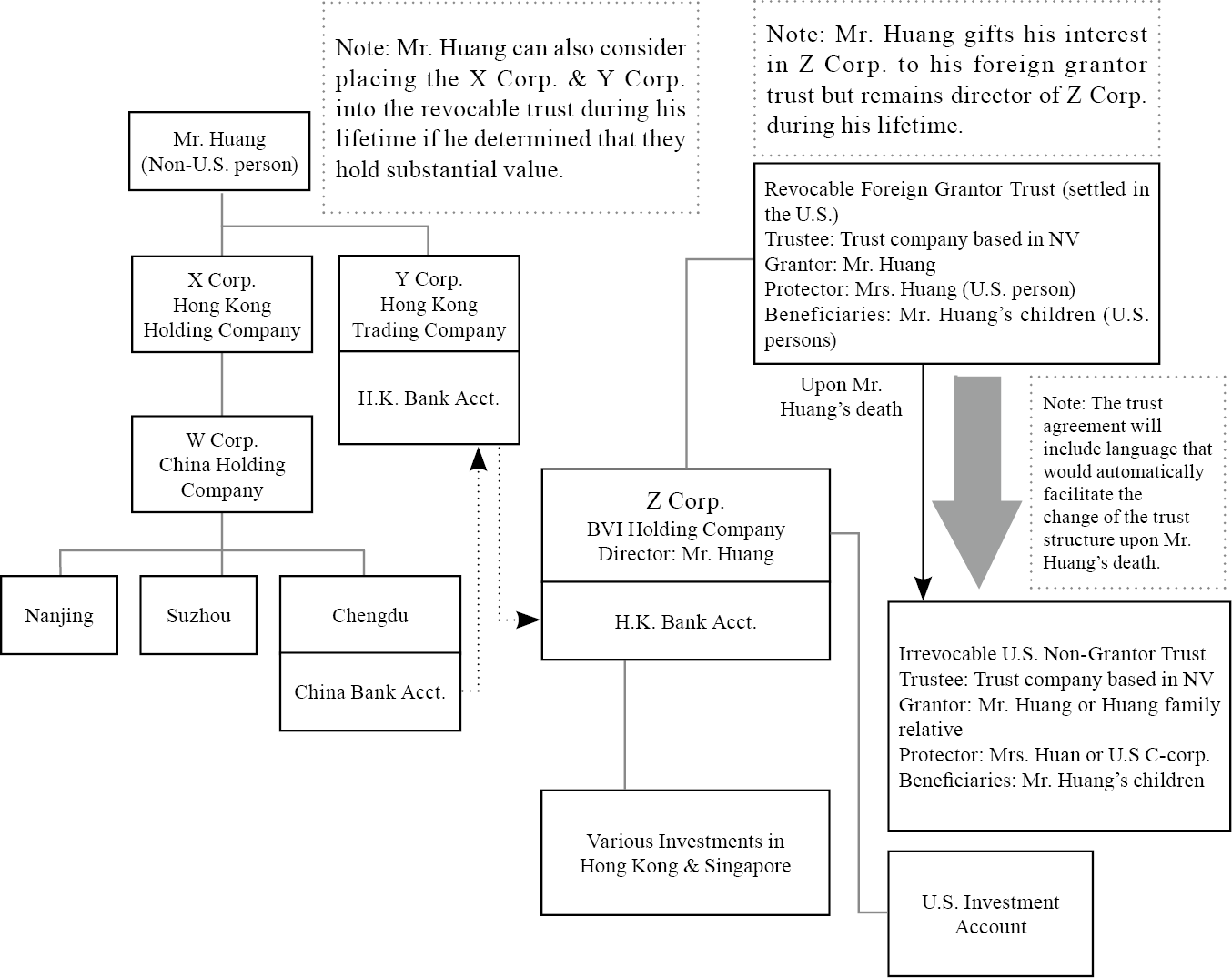

Below is a chart of Mr. Huang’s assets after estate planning:

Analysis:

Mr. Huang, an entrepreneur based in China, owns several factories in Nanjing, Suzhou and Chengdu. His operations in China are held by W Corp., a Chinese holding company. W Corp. is owned by X Corp., a Hong Kong holding company that he holds. Over the years, he has transferred much of the profits from Chengdu to a Hong Kong bank account held by Y Corp., another wholly owned company. Periodically, he transfers funds from his Y Corp. bank account to another Hong Kong bank account held by Z Corp., a British Virgin Islands (BVI) company. Funds accumulated in Z Corp. are invested in various financial products and investments in both Hong Kong and Singapore.

While Mr. Huang is a Chinese citizen and does not have any plans of relocating to the U.S., his wife, daughter and sons are all based in the U.S. and have U.S. citizenship. Over the years, Mr. Huang has come to realize the need to formulate a plan that would allow him to effectively transition his assets to his descendants; however, he is unsure of how to proceed given the complexity of his structures.

Specifically, he had the following questions:

1. How do I effectively delegate responsibilities between my companies’ managers and my descendants?

2. How should I allocate company profits between my companies’ managers and my children?

3. What is a trust? Can a trust help me achieve my succession goals?

4. Which trust jurisdiction is most suitable?

5. Who should I engage to draft the trust agreement or maintain the trust?

6. How should I transfer assets to my trust?

7. Who can manage my trust’s assets once it is established?

8. Who will manage my trust assets after I pass away?

9. Which advisors can help me craft and execute my business succession plans?

Below is a chart of Mr. Huang’s assets prior to estate planning:

Below is a chart of Mr. Huang’s assets after estate planning:

Analysis:

1. Chinese Wealth Creators who wish to transfer their business interests to their descendants must first realize the importance of restructuring their holdings. Oftentimes, this is done by transferring their interest in closely held businesses to offshore companies, often based in Hong Kong, the British Virgin Islands (BVI) or the Cayman Islands. Since Mr. Huang’s wife and children have immigrated to the U.S., it is important for him to consider how he will eventually move some of his assets outside of China, if he wishes to eventually transfer his assets to his family.

2. Fortunately, since Mr. Huang does not have a U.S. Green Card or U.S. citizenship, he remains a non-U.S. person for U.S. income tax purposes. This has several important tax advantages. Since Mr. Huang is generally not considered a U.S. person for income tax purposes, he (and any Foreign Grantor Trust settled and funded exclusively by him) would generally not be liable for U.S. income tax. In addition, gifts that Mr. Huang makes (whether to an individual or to a trust) can be planned for in advance and structured so that it does not trigger any U.S. gift taxes. Lastly, upon Mr. Huang’s death, his assets would generally not be subject to U.S. estate taxation, unless he holds U.S. situs assets for estate tax purposes.

3. In this scenario, Mr. Huang should consider settling a Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT). Since the trust is a grantor trust for U.S. tax purposes, the income tax liability falls on the Mr. Huang (the trust’s grantor). Since Mr. Huang is a non-U.S. person for income tax purposes, non-U.S. situs assets gifted to the trust would continue to be tax free for U.S. tax purposes. Thus, until the FGT becomes a non-grantor trust (generally upon Mr. Huang’s death), non-U.S. sourced income is neither taxable to the trust itself nor to the trust’s beneficiaries. The trust agreement could be drafted to include provisions that would automatically convert the trust to a U.S. non-grantor trust upon Mr. Huang death. This prevents the trust from ever becoming a foreign non-grantor trust for U.S. income tax purposes, which in turn prevents the trust from being taxed unfavorably.

4. By settling a Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT), Mr. Huang does not need to cede control of assets transferred to the trust. Even after Mr. Huang gifts shares of his businesses into a FGT, Mr. Huang can continue to retain full control over the company’s management, voting and board of directors. Furthermore, upon Mr. Huang’s death, assets gifted to the trust can either be (1) distributed to his beneficiaries outright or (2) held in the trust for future generations in perpetuity.

5. Mr. Huang and other Chinese Wealth Creators are frequently approached by family offices or wealth managers who wish for them to settle non-U.S. based trusts. Since Mr. Huang’s spouse and descendants are U.S. persons, settling non-U.S. based trusts (such as one based in the Cayman Islands, Jersey, Guernsey, Nevis or Bahamas) may lead to unexpectedly adverse tax consequences. Distributions from Foreign Non-Grantor Trusts (FNGTs) typically face Throwback Taxes from Undistributed Net Income (UNI), leading to extremely high tax rates if distributions exceed income generated in that year. Furthermore, non-U.S. based trusts often do not have strong legal precedents protecting the trust. By settling a U.S.-based trust, whether the trust be revocable or irrevocable, wealth creators such as Mr. Huang can effectively prevent trust income from being taxed punitively by the U.S.

6. Even if Mr. Huang has already settled a non-U.S. based trust, he should consider (1) “migrating” the trust to the U.S. or (2) transferring or decanting the assets from the existing trust to a new trust based in the U.S. The majority of non-U.S. based trusts have provisions that allow for such a transfer. Though the legal and administrative hurdle of doing so may seem burdensome, a proficient team of cross-border professionals should be able to easily navigate the roadblocks and achieve the desired outcome.

Background:

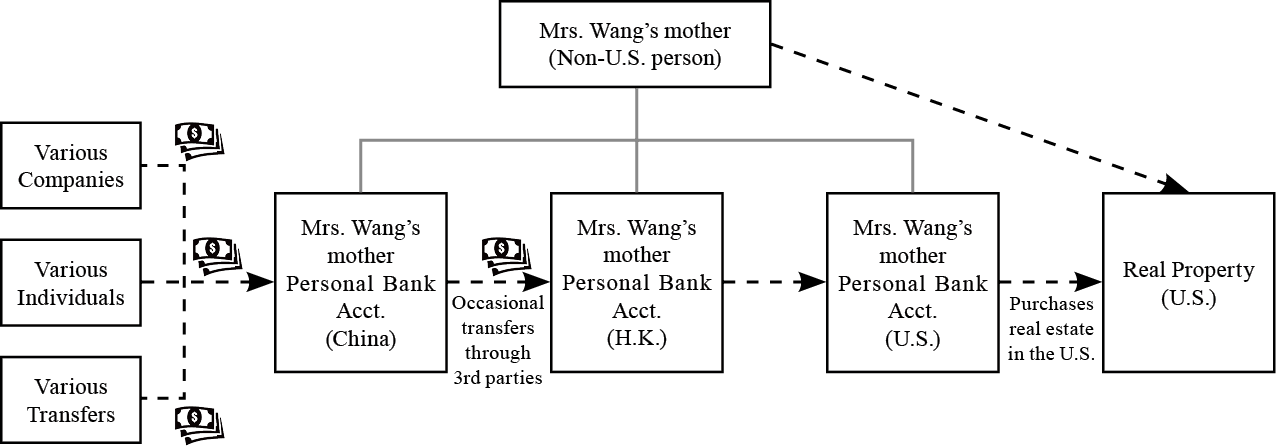

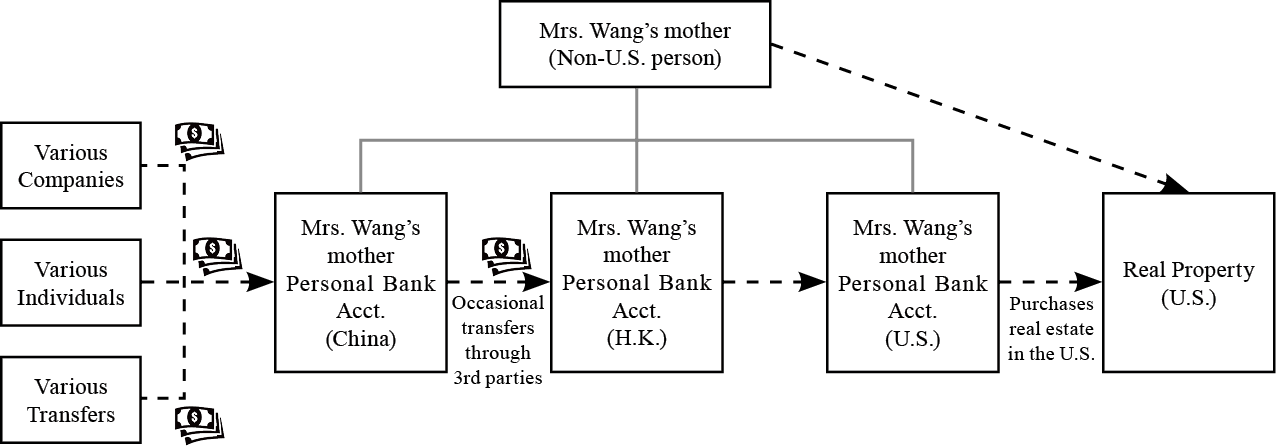

Mrs. Wang is a longstanding executive at a Shanghai-based construction company. Over the years, she has accumulated substantial wealth in China and overseas. Last year, she attained a Green Card through investment in the EB-5 program and moved to the United States with her children. Like many Wealth Creators, Mrs. Wang wished for her descendants to move to the U.S. and settle there permanently. Over the years, she has learned that the U.S. levies hefty taxes on the wealthy. Prior to her becoming a U.S. person (attaining a U.S. green card), she transferred funds to her mother, a Chinese citizen. She then purchased many U.S. properties in the U.S. under her mother’s name.

Two years later, a close friend introduced her to a U.S. accountant, who informed her that U.S. estate taxes are levied not only on U.S. persons, but also foreigners with certain assets in the U.S. Furthermore, the gift and estate tax exemption for foreigners was a mere $60,000 and that any taxable estate in excess of the exemption would generally be subject to a 40% estate tax. Hearing this, Mrs. Wang was in disbelief. She now began searching for a way to decrease her U.S. tax exposure.

Mrs. Wang’s Structure (Prior to Restructuring)

Reflections on Succession:

Succession Framework Analysis:

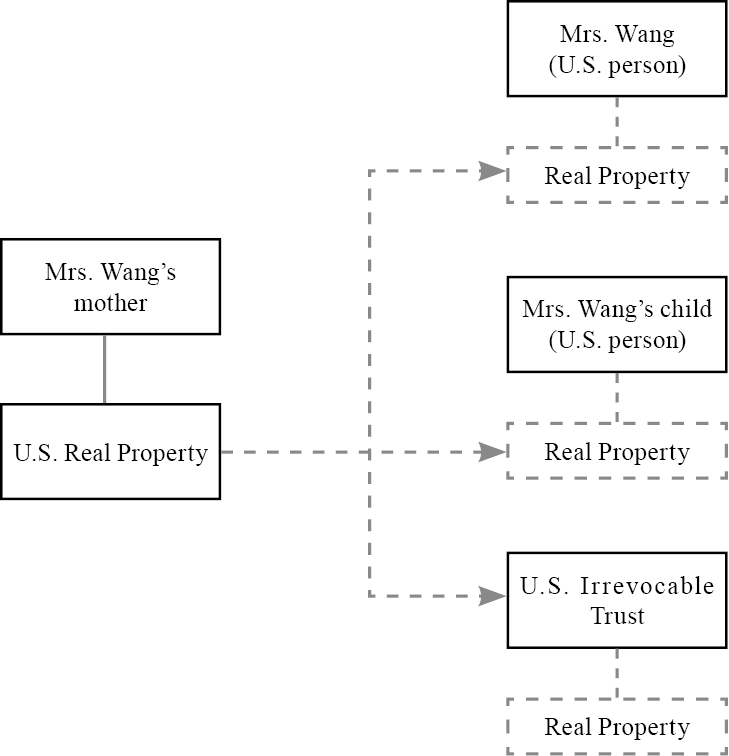

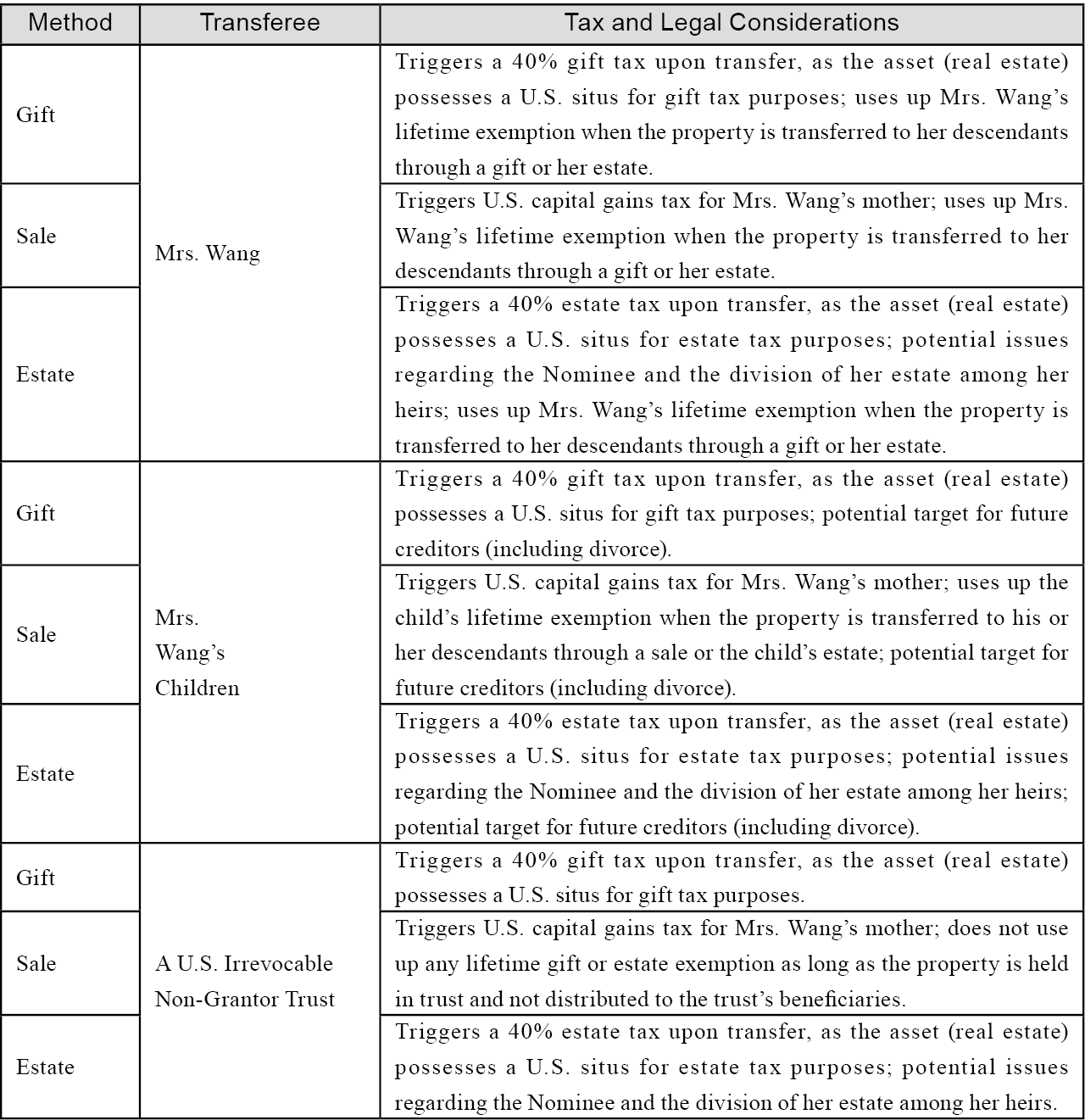

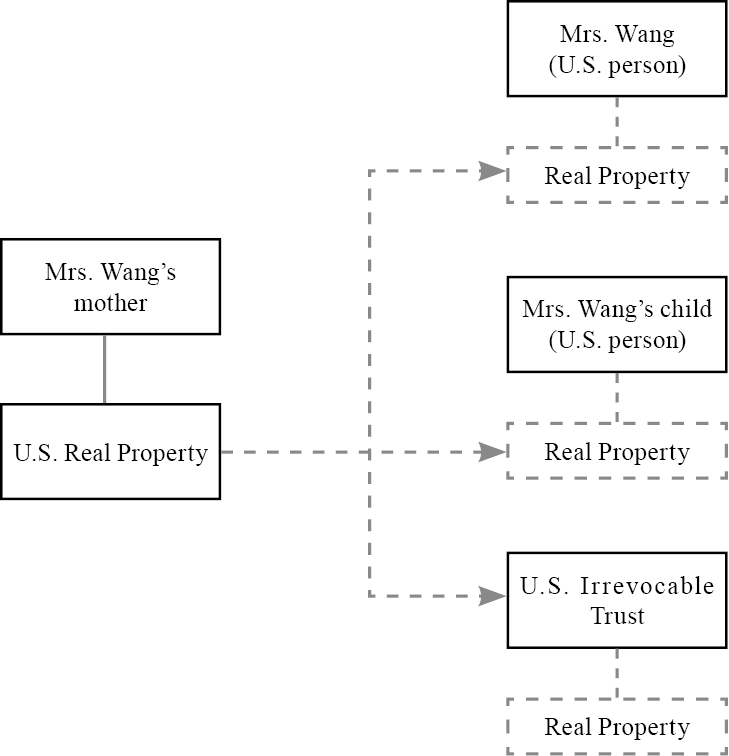

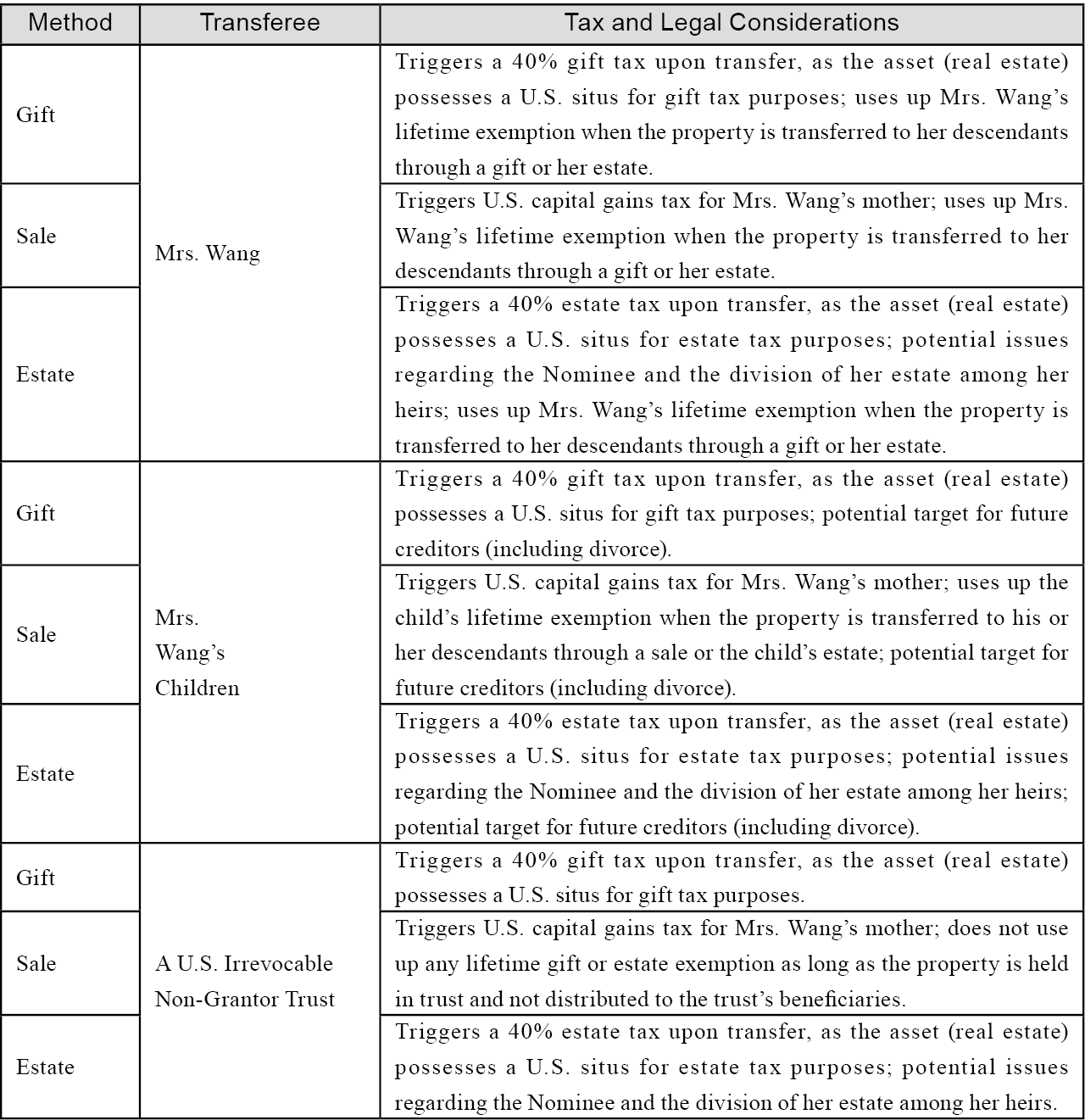

In order to transfer the property from Mrs. Wang’s mother to Mrs. Wang, her children or a U.S. trust, there may be a substantial tax consideration. Furthermore, assets held under individuals may be subject to further U.S. gift and estate taxation and can be a potential target for creditors if any legal disputes arise. Lastly, the Nominee may have other heirs, who may or may not know that the asset does not belong to the Nominee. Potential transfers and their tax and legal effects are summarized below:

Note 1: Taxes are generally taxed at market value and not cost basis, based on the timing of the gift or estate. Typically, valuations of real estate are conducted by licensed real estate appraisers based in the property’s jurisdiction.

Note 2: Lifetime exemption mentioned above refers to the unified lifetime gift and estate tax exemption available to U.S. persons.

Mrs. Wang’s Structure (After Restructuring)

If Mrs. Wang’s mother gifts the real estate to either Mrs. Wang or a U.S. Irrevocable Trust, the gift is taxed at 40% of the property’s market value. If Mrs. Wang chooses to leave the existing structure as is, her mother’s heir would be subject to a 40% estate tax upon her mother’s death. To eliminate U.S. transfer taxes, Mrs. Wang should seek to unwind the previous transaction.

Mrs. Wang is a longstanding executive at a Shanghai-based construction company. Over the years, she has accumulated substantial wealth in China and overseas. Last year, she attained a Green Card through investment in the EB-5 program and moved to the United States with her children. Like many Wealth Creators, Mrs. Wang wished for her descendants to move to the U.S. and settle there permanently. Over the years, she has learned that the U.S. levies hefty taxes on the wealthy. Prior to her becoming a U.S. person (attaining a U.S. green card), she transferred funds to her mother, a Chinese citizen. She then purchased many U.S. properties in the U.S. under her mother’s name.

Two years later, a close friend introduced her to a U.S. accountant, who informed her that U.S. estate taxes are levied not only on U.S. persons, but also foreigners with certain assets in the U.S. Furthermore, the gift and estate tax exemption for foreigners was a mere $60,000 and that any taxable estate in excess of the exemption would generally be subject to a 40% estate tax. Hearing this, Mrs. Wang was in disbelief. She now began searching for a way to decrease her U.S. tax exposure.

Mrs. Wang’s Structure (Prior to Restructuring)

Reflections on Succession:

1. The use of nominees for holding structures is common in China and may pose a number of significant obstacles to wealth preservation and transfer.

Wealth Creators in China are accustomed to holding assets under the names of others (“Nominees”), since they see minimal risks of doing so. Though nominee usage is prevalent in China, Wealth Creators who use nominees to hold assets outside of China may face considerable challenges.

Unlike in China, under U.S. laws, if the Wealth Creator were to challenge the legitimacy of the nominee’s ownership over an asset, they would need to assert a reasonable legal claim over the said asset. In the U.S., an agreement to hold an asset on someone else’s behalf could be viewed as insufficient to justify ownership. Thus, if the loyalty of the Nominee is at risk, the true owner of the assets can expect to face considerable odds when reasserting ownership.

Assuming the Nominee remains loyal to the Wealth Creator, the nominee’s health could potentially be another concern. If the Nominee were to pass away while holding considerable assets, those assets may (1) be subject to substantial taxation in the U.S. or (2) subject to division per the Nominee’s estate or last will. In many cases the Nominee’s family may not be willing to cooperate or may even not be aware of arrangements between the Nominee and the “true” owner.

A last consideration would be the Nominee’s legal status. In the past, we’ve encountered situations in which even the Wealth Creator was unaware of the Nominee attaining a new citizenship or permanent residence (green card) in the U.S. or another jurisdiction. While these situations are rare, they may pose a considerable taxation risk to the Wealth Creator if improperly supervised or managed.

2. When moving assets into the U.S., Wealth Creators must explain their source(s) of wealth.

When creating U.S. accounts or moving cash into U.S. accounts, the Wealth Creator generally must declare his or her source(s) of wealth and his or her estimated total net worth at account opening. When transferring amounts in excess of $1 million (USD), we recommend Wealth Creators find qualified professionals to assist them with their transfers. Furthermore, our recommendation is to find professionals who are accustomed to assisting clients who receive large transfers from outside of the U.S. Once assets fall under U.S. jurisdiction, the financial institution itself, the U.S. Treasury Department or even the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) may question the source(s) of funds or request additional information including evidence of past transfers or income taxes paid. Competent professionals are able to both prepare the relevant documentation and assist the clients in preparing a proper written response to the questions posed.

3. Wealth Creators often wish to open bank accounts quickly in order to purchase U.S. real estate and financial products under the names of their foreign relatives, friends, or associates.

They may see this as an opportunity to invest in the U.S., while minimizing their U.S. tax exposure and disclosure obligations; however, many may falsely believe that the U.S. does not impose an estate tax on foreigners with U.S. holdings.

Furthermore, real estate brokers or investment management personnel often urge Wealth Creators to quickly transfer funds in order to further their own agendas (primarily their commissions and fees), without fully understanding or explaining the relevant tax and regulatory consequences of the proposed transactions. They may even make claims such as “don’t worry, the CPA will take care of your concerns.”

To minimize tax consequences and regulatory risk, we recommend that Wealth Creators find advisors who can address all aspects of wealth transfer at least 6-18 months prior to moving assets into the U.S. This team should consist of accountants who can analyze U.S. income, estate and gift taxes, attorneys who can analyze cross-border legal structures and secretaries who can manage U.S. and overseas fund transfers (often through financial institutions in Hong Kong and Singapore) and deliver sufficient evidence of the client’s source(s) of wealth.

Succession Framework Analysis:

In order to transfer the property from Mrs. Wang’s mother to Mrs. Wang, her children or a U.S. trust, there may be a substantial tax consideration. Furthermore, assets held under individuals may be subject to further U.S. gift and estate taxation and can be a potential target for creditors if any legal disputes arise. Lastly, the Nominee may have other heirs, who may or may not know that the asset does not belong to the Nominee. Potential transfers and their tax and legal effects are summarized below:

Note 1: Taxes are generally taxed at market value and not cost basis, based on the timing of the gift or estate. Typically, valuations of real estate are conducted by licensed real estate appraisers based in the property’s jurisdiction.

Note 2: Lifetime exemption mentioned above refers to the unified lifetime gift and estate tax exemption available to U.S. persons.

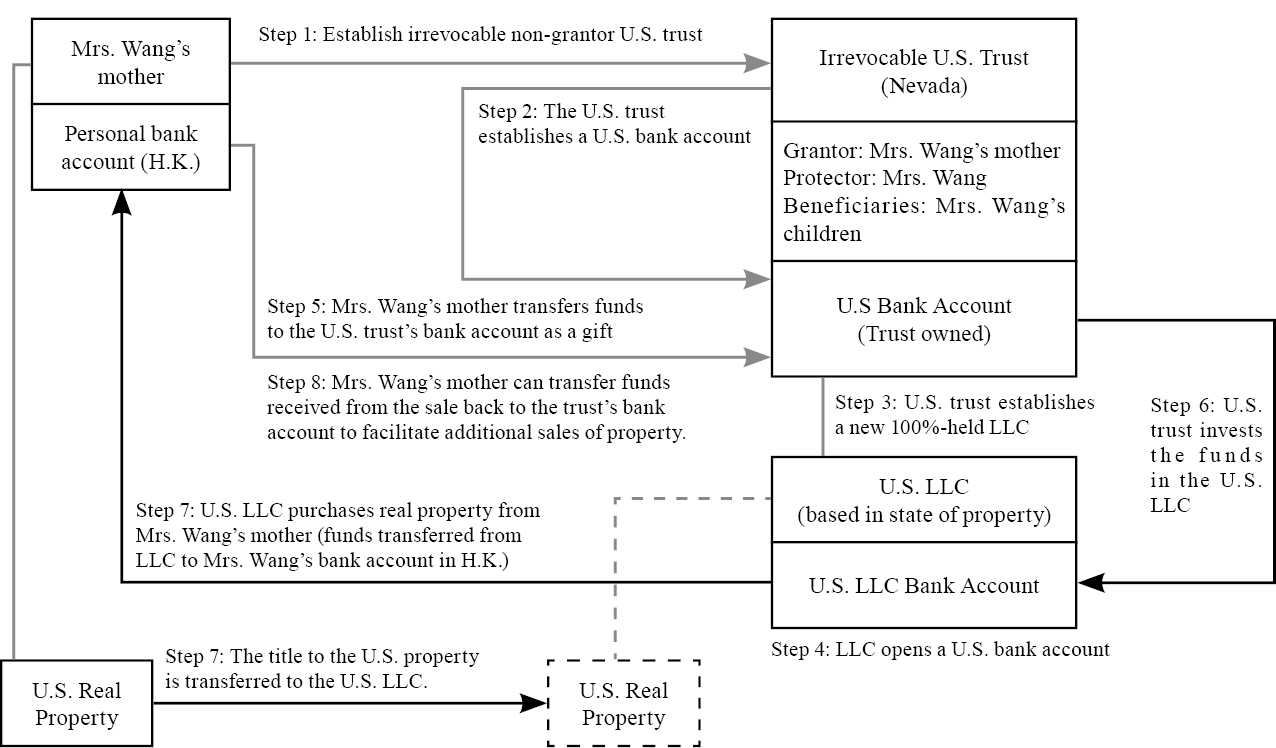

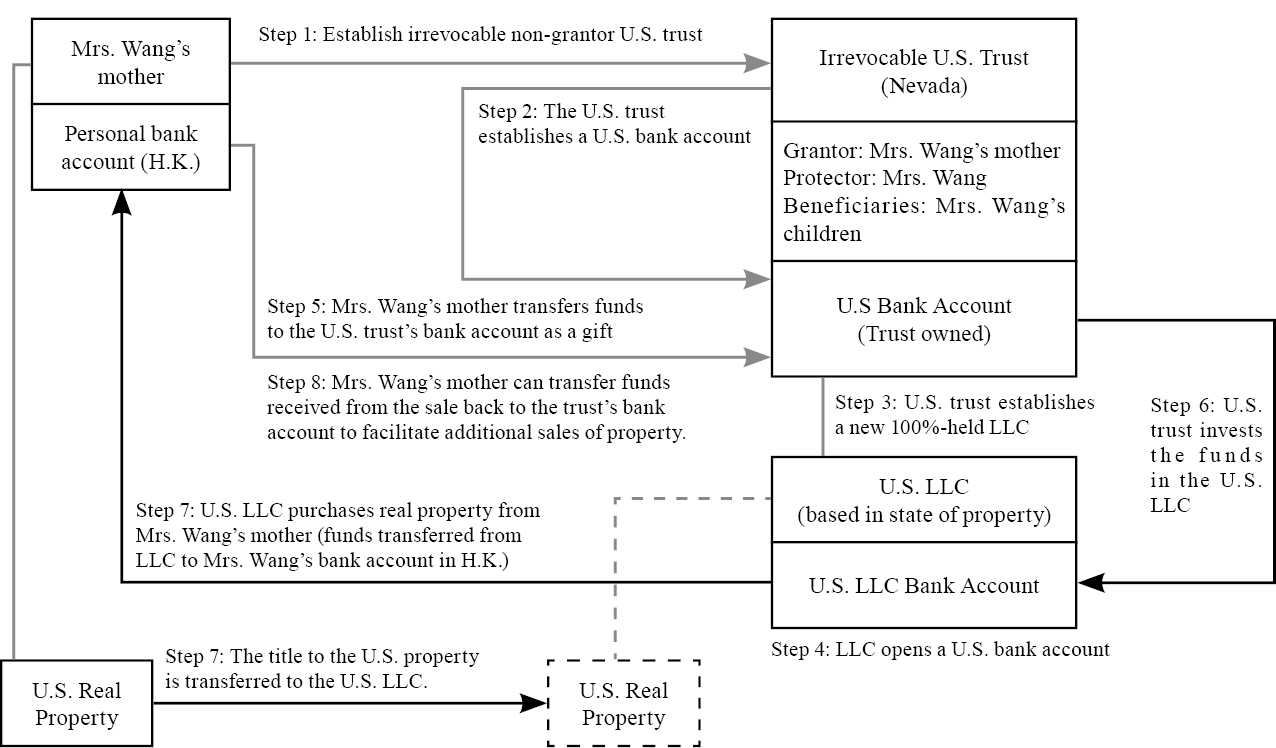

Mrs. Wang’s Structure (After Restructuring)

If Mrs. Wang’s mother gifts the real estate to either Mrs. Wang or a U.S. Irrevocable Trust, the gift is taxed at 40% of the property’s market value. If Mrs. Wang chooses to leave the existing structure as is, her mother’s heir would be subject to a 40% estate tax upon her mother’s death. To eliminate U.S. transfer taxes, Mrs. Wang should seek to unwind the previous transaction.

1. In these situations, we recommend that Mrs. Wang’s mother first establish a U.S. Irrevocable Non-Grantor Trust. Mrs. Wang, a U.S. person, can serve as the Trust Protector of this trust. Her children and / or other persons determined by Mrs. Wang can be selected as beneficiaries of the trust.

2. The Trust can then establish a U.S. bank account.

3. The Trust can then establish a 100% owned U.S. Limited Liability Company (LLC)

4. The LLC can then open U.S. LLC bank checking account(s), after applying for an Employer Identification Number (EIN) with the IRS through Form SS-4.

5. Mrs. Wang’s mother gifts funds from her personal bank account outside of the U.S. (typically in Hong Kong or Singapore) into a bank account set up by the U.S. Trust.

6. A direction letter is drafted by Mrs. Wang to instruct the Nevada trustee to transfer the funds from the trust’s bank account to the LLC’s U.S. bank account.

7. The U.S. LLC hires a real estate appraiser and appraises the property that will be sold. The U.S. LLC then purchases the property from Mrs. Wang’s mother at the value determined through a property’s appraisal, transferring proceeds from the sale to a bank account held by Mrs. Wang’s mother.

8. If proceeds are transferred to Mrs. Wang’s mother’s bank account outside the U.S., the funds can be transferred back to the U.S. after the transaction is complete. The funds, now in the LLC’s U.S. bank account, can then be used to purchase additional real estate (or stakes of real estate) held by Mrs. Wang’s mother. If proceeds are transferred to Mrs. Wang’s mother’s bank account in the U.S., we recommend that funds be transferred from her U.S. bank account back to her offshore bank account prior to transferring the funds back into the U.S. LLC.

9. Since the U.S. real estate is now held by the U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust, Mrs. Wang’s mother’s death would no longer trigger U.S. estate tax for the real estate sold to the trust-owned LLC.

Background:

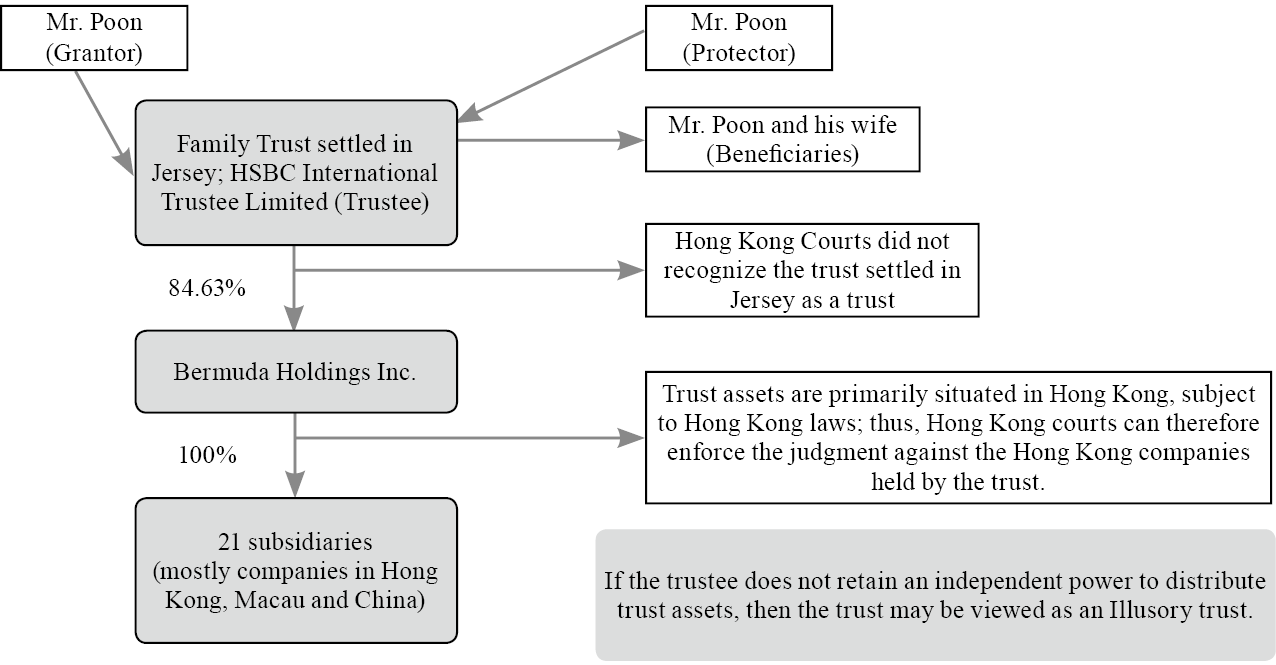

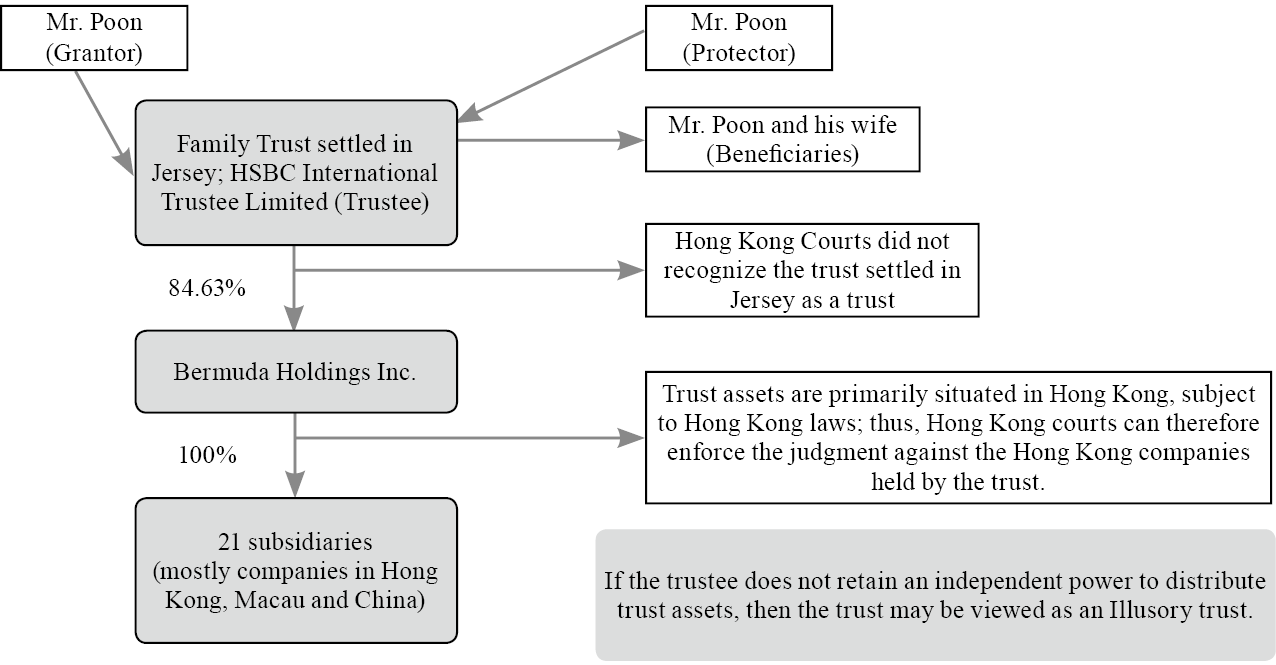

In the past decades, Wealth Creators often used offshore trusts settled in various jurisdictions to protect their assets. Otto Poon, the founder of Analogue Holdings, settled an irrevocable discretionary Jersey Trust in July 1995. He served as the Trust’s Grantor, the Trust Protector, and one of the Trust’s Beneficiaries. HSBC’s Trust Company was appointed as trustee of his trust. After the Trust was established, he gifted 85% of his holdings in Analogue to his trust.

Since Mr. Poon still retained effective control over to the trust assets, the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal held that the trust assets were includible in his matrimonial assets. The trust thus did not serve its intended purpose.

Reflections on Succession:

At the time of the ruling, the court decision shocked many Wealth Creators, who previously believed that their assets would be thoroughly protected by offshore trusts no matter whether they held substantial control over the trust’s assets or not.

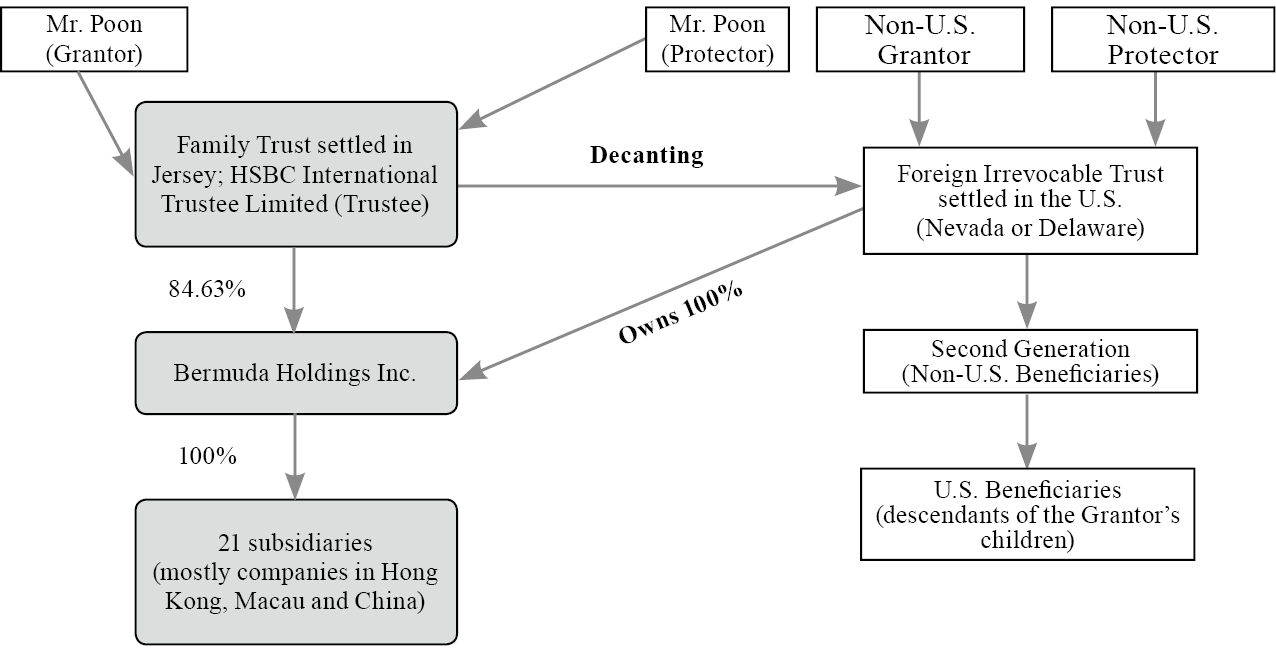

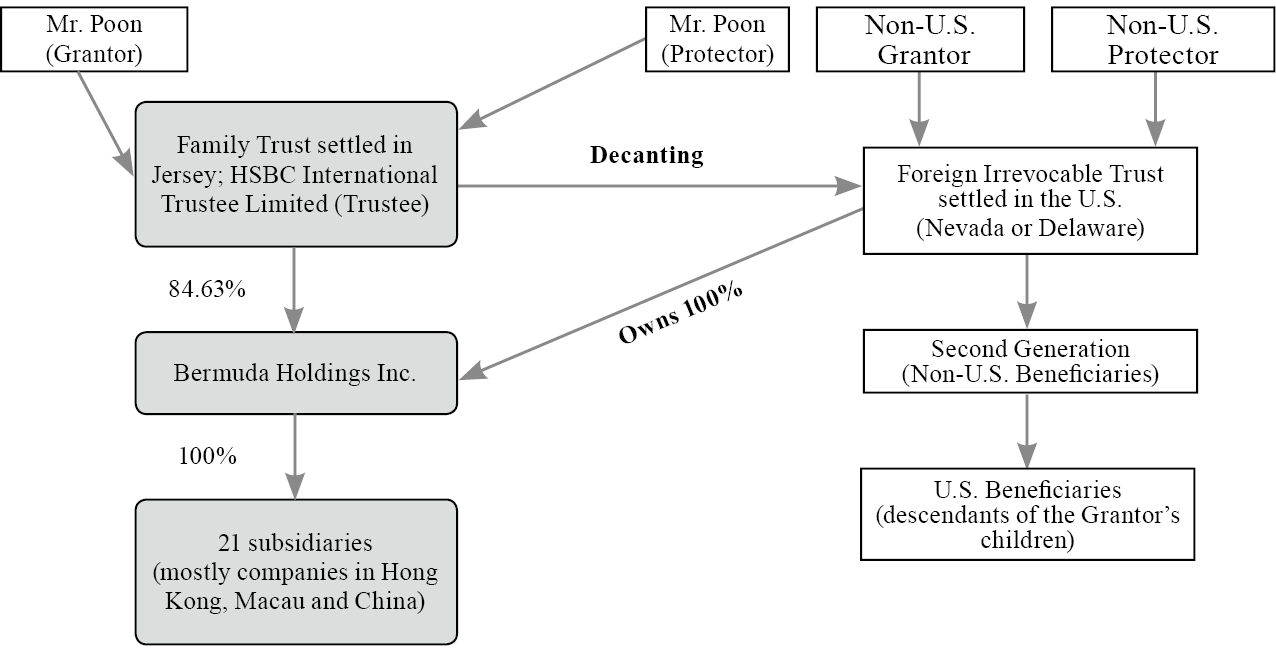

In Structure (2), since the primary purpose of such trusts is to protect the trust’s assets and to pass these assets on to the trust’s beneficiaries, powers are more often clearly delineated, with the grantor retaining minimal to no powers. We advise that families seeking to create these structures find competent legal counsel in all applicable jurisdictions in order to ensure that the assets held in these trusts would be protected and that the trust would be treated as an entity independent from the trust’s grantor, protector, and beneficiaries.

Succession Framework Proposal:

The Offshore Trust (Prior to Restructuring)

Suggested Structure

Succession Framework Analysis:

While offshore trusts have long been a mainstay for wealthy families, balancing the need for control with the asset protection qualities of a trust is important to keep in mind. If the trust’s grantor retains many powers over the trust, courts may view the trust skeptically or, in a worst-case scenario, deny that the trust ever existed. This could potentially cause assets to be seized by creditors. The following steps are crucial for determining whether a trust is able to serve its function and protect assets from potential creditors:

In the past decades, Wealth Creators often used offshore trusts settled in various jurisdictions to protect their assets. Otto Poon, the founder of Analogue Holdings, settled an irrevocable discretionary Jersey Trust in July 1995. He served as the Trust’s Grantor, the Trust Protector, and one of the Trust’s Beneficiaries. HSBC’s Trust Company was appointed as trustee of his trust. After the Trust was established, he gifted 85% of his holdings in Analogue to his trust.

Since Mr. Poon still retained effective control over to the trust assets, the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal held that the trust assets were includible in his matrimonial assets. The trust thus did not serve its intended purpose.

Reflections on Succession:

At the time of the ruling, the court decision shocked many Wealth Creators, who previously believed that their assets would be thoroughly protected by offshore trusts no matter whether they held substantial control over the trust’s assets or not.

1. There are generally three types of offshore trust structures:

(1)A client’s private bank representative or wealth advisor creates a trust structure to facilitate investment of the client’s assets.

(2)A client retains a professional trust company and establishes a trust for the primary purpose of asset protection or succession planning.

(3)A client retains attorneys and a trust company for assistance with settling a private trust company (PTC).

When establishing an offshore trust, the Wealth Creator should evaluate the pros and cons of each jurisdiction. Typically, if there is a dispute, complaints would be filed in the jurisdiction that the trust company is situated and not where the trust assets are situated. Wealth Creators that seek to protect their assets through establishing a trust should seek jurisdictions with strong case law as a basis for providing those protections.

In Structure (1), described above, private bankers and wealth managers attempt to recommend trusts that (A) maximize the investment advisor’s control over the trust, (B) minimize the trust’s tax liability and (C) maximize the grantor’s retained powers. As the grantor often retains substantially all powers (including the power to invest the trust assets, the power to distribute the trust assets and the power to determine trust beneficiaries), these types of trusts typically suffer from a lack of independence. Since the trust lacks independence, many competent courts would and have ruled that these trusts never existed and that the grantor has retained his interest in assets “gifted” to the trust, thus opening the trust’s assets up for distribution to the grantor’s creditors. These trusts are often referred to as “Illusory Trusts.”

In Structure (2), since the primary purpose of such trusts is to protect the trust’s assets and to pass these assets on to the trust’s beneficiaries, powers are more often clearly delineated, with the grantor retaining minimal to no powers. We advise that families seeking to create these structures find competent legal counsel in all applicable jurisdictions in order to ensure that the assets held in these trusts would be protected and that the trust would be treated as an entity independent from the trust’s grantor, protector, and beneficiaries.

In Structure (3), Wealth Creators may be persuaded to establish a Private Trust Company (PTC) either in an offshore jurisdiction or even in the U.S. While a PTC can and often do provide certain protections, they often also come with immense and immediate setup and maintenance costs (often exceeding US$200,000 per year). Highly customized and extremely complex, PTCs may not be suitable for most families and certainly can make the process of cross-border wealth transfers an even more daunting task.

2. While many jurisdictions offer grantors flexibility to retain certain powers in a bid to win their business, offshore trusts, generally settled on offshore islands or territories, often provide the maximum amount of flexibility. For many years, this was seen as a boon for professionals (especially attorneys specializing in offshore trusts); however, as clearly illustrated in this case, a high degree of control may lead other jurisdictions to disregard the trust structure in its entirety. The risk of a trust being recognized as an “illusory trust” is increasing, as more and more competent jurisdictions realize that an offshore trust is only a trust in name and not in substance.

Succession Framework Proposal:

The Offshore Trust (Prior to Restructuring)

Suggested Structure

Succession Framework Analysis:

While offshore trusts have long been a mainstay for wealthy families, balancing the need for control with the asset protection qualities of a trust is important to keep in mind. If the trust’s grantor retains many powers over the trust, courts may view the trust skeptically or, in a worst-case scenario, deny that the trust ever existed. This could potentially cause assets to be seized by creditors. The following steps are crucial for determining whether a trust is able to serve its function and protect assets from potential creditors:

1. When reviewing a trust agreement, advisers typically focus on the grantor’s intent. Typically, trusts are settled either to protect the Grantor’s assets or reduce tax-related risks. Another important aspect to consider are the grantor and his or her descendants’ current and future tax residencies. We especially recommend families that are drafting trusts with U.S. beneficiaries seek competent U.S. tax counsel to determine the tax effects of offshore trusts.

2. Trust agreements should be drafted so that grantors do not have powers that would jeopardize the trust’s independence. If the trust agreement provides for a trust protector (generally a fiduciary in charge of the most impactful functions of a trust), the grantor and the trust’s beneficiaries should not also serve as the trust protector. Doing so may reduce the likelihood of the trust being deemed an illusory or ineffective trust.

3. When preparing a structure that includes a trust, advisers should consider potential gift and estate tax consequences for the grantor, the trust protector, the beneficiaries, and the trust itself. Failure to do so may result in adverse tax consequences.

4. For families with any U.S. nexus (one or more U.S. grantor, protector, beneficiary, or asset), we would recommend evaluating the pros and cons of U.S. trusts versus offshore trust structures. For families with existing offshore trust(s), we recommend looking to see whether migrating the trust to the U.S. or decanting the assets to a U.S. trust is possible. While this often requires the assistance of U.S. and non-U.S. counsel, the relative stability of a U.S. legal jurisdiction and its consistent set of protective trust laws is almost always worth the effort.

5. U.S. trusts (including foreign trusts settled in the U.S. for U.S. income tax purposes) are typically drafted or reviewed by attorneys in the state that the trust is settled. Typically, those attorneys also give an opinion regarding the independence of the trust. Tax counsel would also usually a separate opinion regarding potential U.S. tax consequences.

Background:

Mr. Jiang and Mrs. Jiang, a married couple residing in China, finally received notices that they were granted their U.S. Permanent Resident Cards (Green Cards) after more than a decade. As they were not sure that they were going to ever receive their green cards, they never considered the tax consequences of their U.S. residency status. When they came to the U.S., they consulted with trusted U.S. CPAs, who informed them that their worldwide assets would now be subjected to U.S. income, gift, and estate taxes, much to their disbelief.

Reflections on Succession:

1. Over the past couple of years, Hong Kong, Australia, and Canada have increasingly tightened their immigration policies. The enactment of EB-5 in the U.S. came as a relief to many Chinese families seeking to permanently relocate their families. Tax advisors often advised Wealth Creators to retain their original citizenships and tax residency, while their spouses applied for Green Cards, since the U.S. generally taxes its residents more heavily. However, since many Chinese nationals believe that a married couple should stay together indefinitely and never separate, we frequently see both the Wealth Creator and their spouses attain Green Cards.

2. Once a foreign national obtains a Green Card and becomes a U.S. tax resident, he or she is liable for not only U.S. income taxes on his or her worldwide income, but also subject to disclosure requirements of his or her offshore assets in accordance with numerous U.S. laws and regulations. Many wonder whether there is a way to attain U.S. permanent residency, without the enormous tax and disclosure responsibilities that come with it. For those that created their wealth outside of the U.S., is there a path to U.S. citizenship without payment of considerable income, estate and gift taxes?

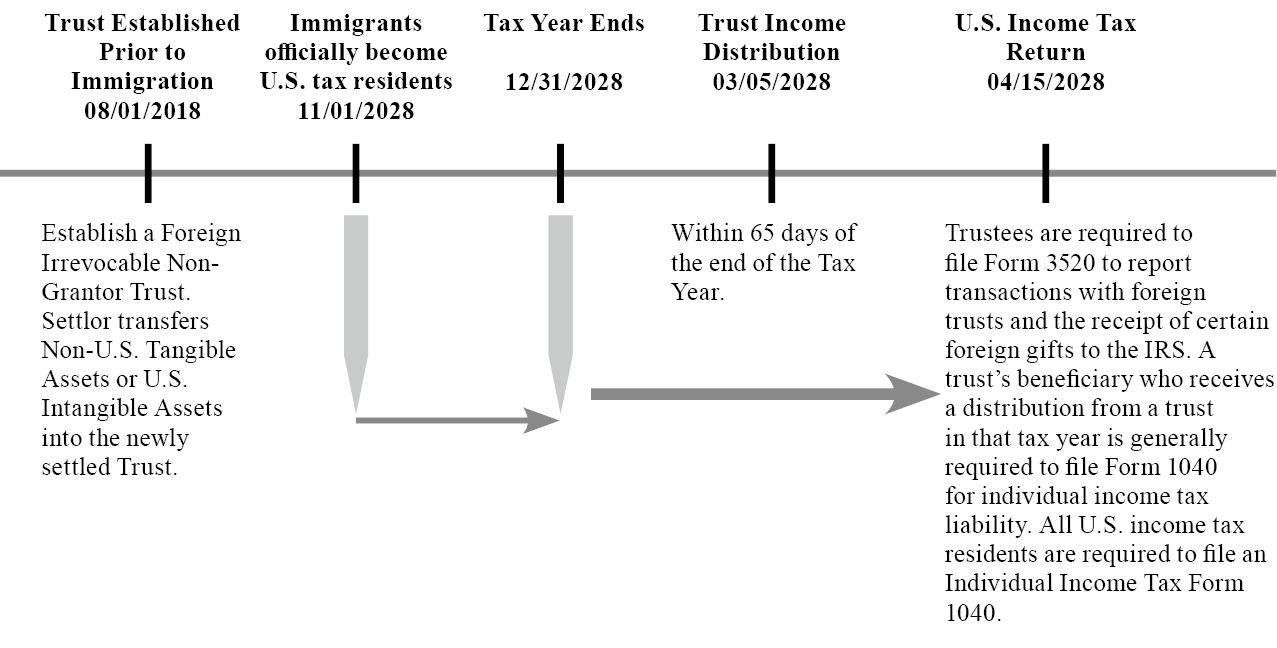

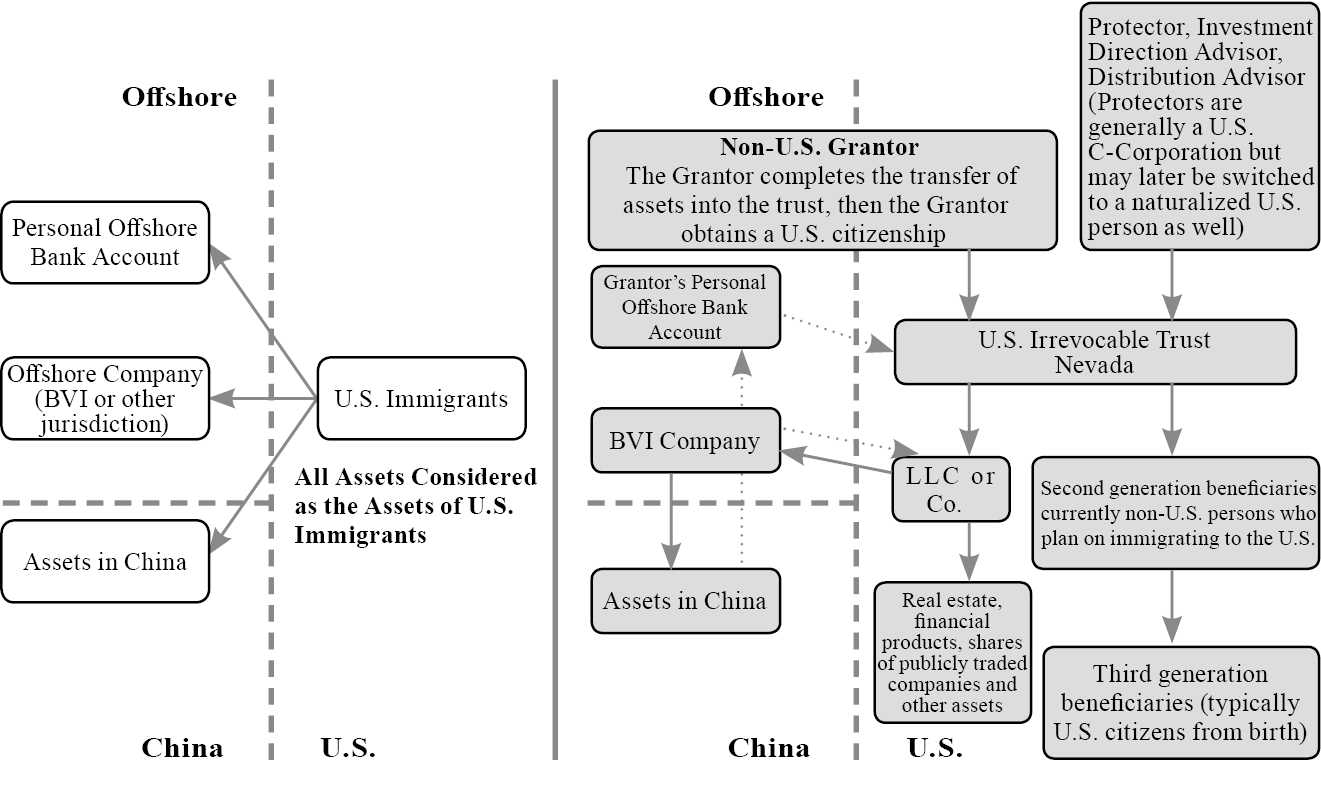

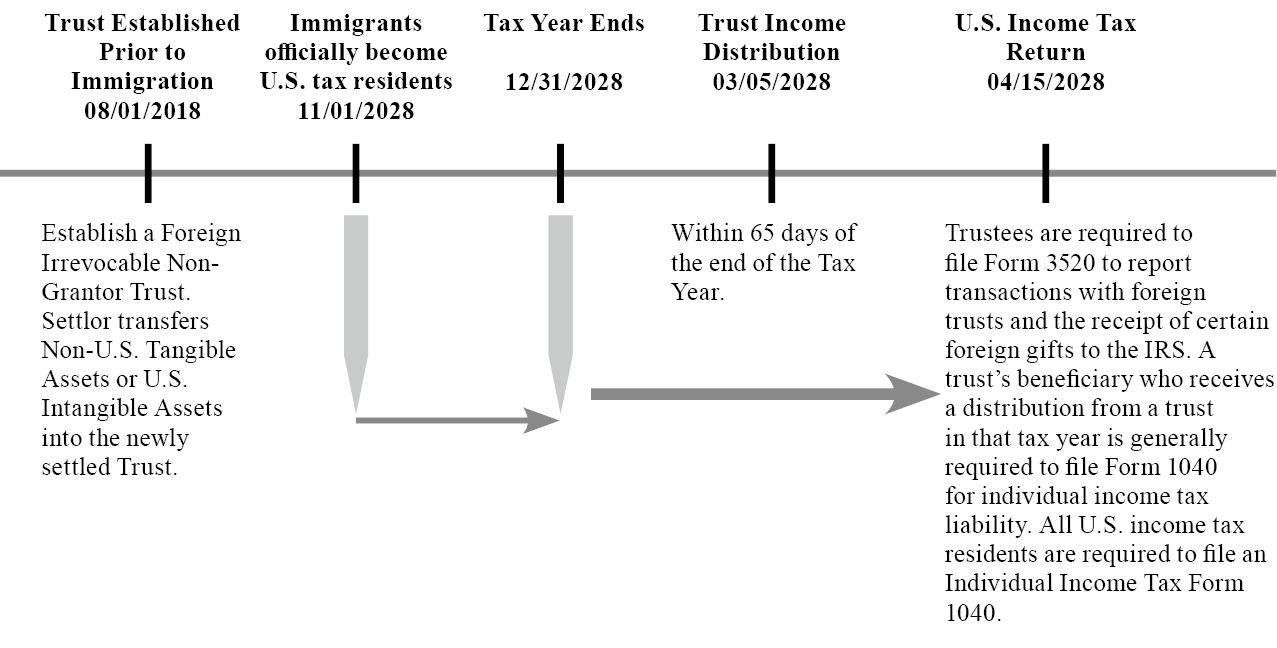

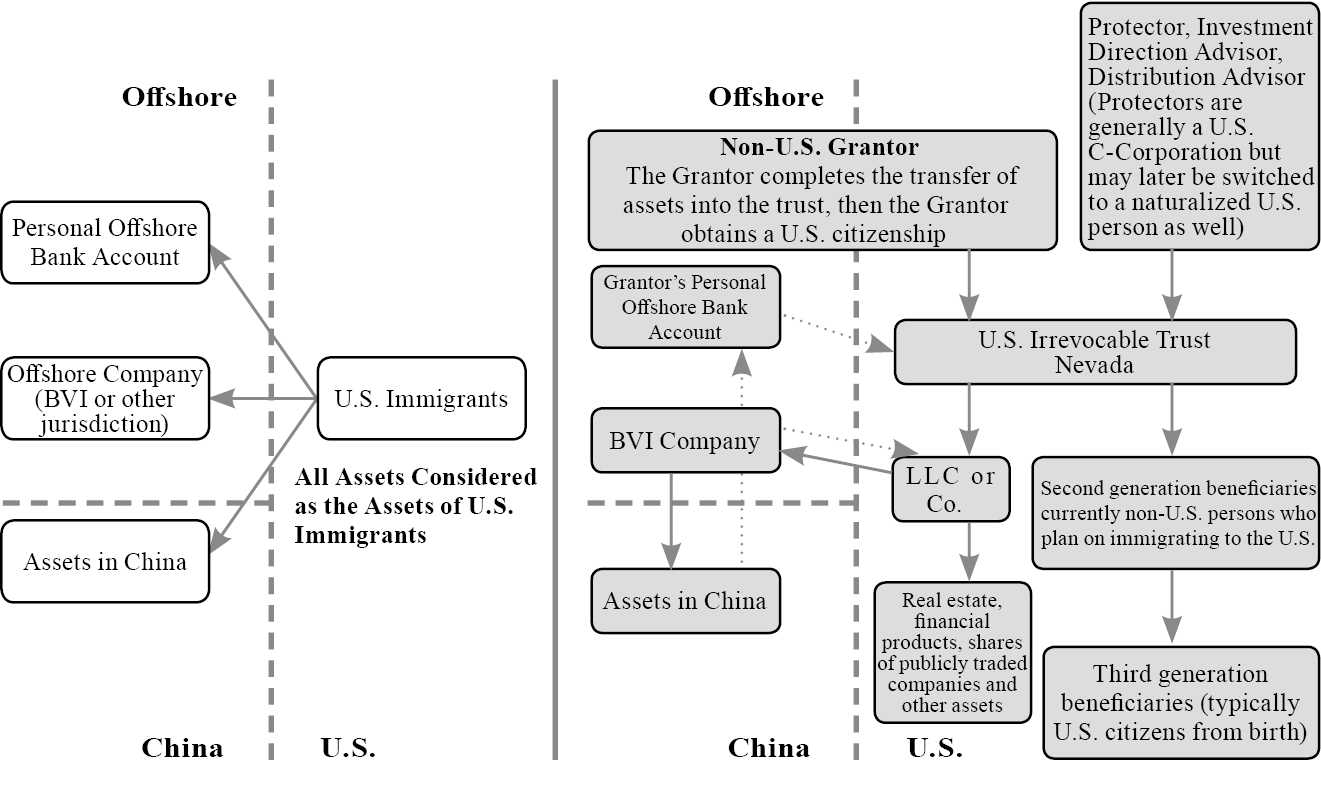

Succession Framework Proposal

Succession Framework Analysis:

2. Families immigrating to the U.S. often wish to transfer part or all of their wealth from foreign jurisdictions into the U.S. We generally recommend families bringing in excess of $2 million seek guidance from licensed professionals to increase their understanding of the U.S. tax and legal systems.

3. For U.S.-bound individuals with significant wealth, settling a U.S. non-grantor trust may help with both minimizing applicable taxes and asset protection. Individuals with assets in excess of the lifetime U.S. gift and estate tax exemption may be subject to a 40% estate tax for assets above that threshold. The tax is levied on both assets attained before and after an individual immigrates to the U.S. Additionally, individuals who wish to make gifts or leave assets in excess of their lifetime exemption to those 37.5 years younger may face an additional transfer tax, the U.S. Generation-Skipping Tax (GST).

4. When settling certain U.S. trusts, both individuals and corporations may be named as fiduciaries. U.S. trusts are typically established and funded by its grantor with governance allocated among the trust’s fiduciaries (typically, the Trust Protector, the Distribution Advisor, and the Investment Direction Advisor, among others).

In Directed Trusts, the Trustee generally handles the administrative and secretarial functions of the trust. It is generally advisable for Wealth Creators to seek out the services of a licensed Trust Company to act as the Trustee. Doing so ensures that there is ongoing oversight of the trust and that the various secretarial functions are being monitored. Trust companies serving as Trustee of directed trusts typically charge a flat annual fee rather than a percentage of assets under administration.

5. While gifts from non-U.S. persons are often tax-free, Wealth Creators who are considering gifts above $2 million (USD) should consider making the gift to a trust for the intended Beneficiary, rather than making a gift directly to the Beneficiary. Since the recipient of the gift is the trust itself rather than an individual, the trustee of the trust would file Form 3520 to report the gift. As a trust receiving large sums is more common, it is less likely to be scrutinized than if an individual were to receive the large gift.

6. U.S. persons receiving distributions from or controlling foreign trusts often face unfavorable or even punitive U.S. income tax consequences. As such, Wealth Creators seeking to immigrate the U.S. should consider unwinding their non-U.S. trusts in favor of U.S. trusts. Even Wealth Creators who are not personally seeking to immigrate to the U.S. but have U.S. descendants should consider shifting their assets into U.S. trusts, as they are generally more protective of U.S. descendants both from an asset protection perspective and from a U.S. tax perspective. When structured properly, moving assets into a U.S. trust can lead to (1) a clearer wealth transfer structure, (2) preferable tax treatment, (3) stronger asset protection and (4) lower ongoing maintenance costs (relating to both Trustee fees and accounting and disclosure requirements).

Mr. Jiang and Mrs. Jiang, a married couple residing in China, finally received notices that they were granted their U.S. Permanent Resident Cards (Green Cards) after more than a decade. As they were not sure that they were going to ever receive their green cards, they never considered the tax consequences of their U.S. residency status. When they came to the U.S., they consulted with trusted U.S. CPAs, who informed them that their worldwide assets would now be subjected to U.S. income, gift, and estate taxes, much to their disbelief.

Reflections on Succession:

1. Over the past couple of years, Hong Kong, Australia, and Canada have increasingly tightened their immigration policies. The enactment of EB-5 in the U.S. came as a relief to many Chinese families seeking to permanently relocate their families. Tax advisors often advised Wealth Creators to retain their original citizenships and tax residency, while their spouses applied for Green Cards, since the U.S. generally taxes its residents more heavily. However, since many Chinese nationals believe that a married couple should stay together indefinitely and never separate, we frequently see both the Wealth Creator and their spouses attain Green Cards.

2. Once a foreign national obtains a Green Card and becomes a U.S. tax resident, he or she is liable for not only U.S. income taxes on his or her worldwide income, but also subject to disclosure requirements of his or her offshore assets in accordance with numerous U.S. laws and regulations. Many wonder whether there is a way to attain U.S. permanent residency, without the enormous tax and disclosure responsibilities that come with it. For those that created their wealth outside of the U.S., is there a path to U.S. citizenship without payment of considerable income, estate and gift taxes?

Succession Framework Proposal

Succession Framework Analysis:

1. Wealthy families planning on immigrating to the U.S. often consider investing in U.S. real estate. Prior to becoming U.S. persons, Wealth Creators should consult with tax and legal advisors and discuss the options available to achieve both the taxes minimization and asset protection.

2. Families immigrating to the U.S. often wish to transfer part or all of their wealth from foreign jurisdictions into the U.S. We generally recommend families bringing in excess of $2 million seek guidance from licensed professionals to increase their understanding of the U.S. tax and legal systems.

3. For U.S.-bound individuals with significant wealth, settling a U.S. non-grantor trust may help with both minimizing applicable taxes and asset protection. Individuals with assets in excess of the lifetime U.S. gift and estate tax exemption may be subject to a 40% estate tax for assets above that threshold. The tax is levied on both assets attained before and after an individual immigrates to the U.S. Additionally, individuals who wish to make gifts or leave assets in excess of their lifetime exemption to those 37.5 years younger may face an additional transfer tax, the U.S. Generation-Skipping Tax (GST).

4. When settling certain U.S. trusts, both individuals and corporations may be named as fiduciaries. U.S. trusts are typically established and funded by its grantor with governance allocated among the trust’s fiduciaries (typically, the Trust Protector, the Distribution Advisor, and the Investment Direction Advisor, among others).

The trust’s Beneficiary (or Beneficiaries) may receive distributions from the trust in accordance with the trust agreement, which is further categorized as income distributions or principal distributions. Many trust agreements are drafted so that the Beneficiaries are not legally entitled to any distributions for asset protection purposes. It can be drafted so that the trust’s Distribution Advisor has full discretion as to the amount of any distribution paid to the trust’s Beneficiaries (or even if the Beneficiaries receive any distribution at all). Doing this would generally protect the trusts’ assets from any creditors of the Beneficiaries of the trust.

Note: For a detailed explanation of the various roles and responsibilities in a U.S. Trust, please refer to the section of Chapter 2 that discusses Determining the Roles in a Nevada Irrevocable Trust.

In Directed Trusts, the Trustee generally handles the administrative and secretarial functions of the trust. It is generally advisable for Wealth Creators to seek out the services of a licensed Trust Company to act as the Trustee. Doing so ensures that there is ongoing oversight of the trust and that the various secretarial functions are being monitored. Trust companies serving as Trustee of directed trusts typically charge a flat annual fee rather than a percentage of assets under administration.

5. While gifts from non-U.S. persons are often tax-free, Wealth Creators who are considering gifts above $2 million (USD) should consider making the gift to a trust for the intended Beneficiary, rather than making a gift directly to the Beneficiary. Since the recipient of the gift is the trust itself rather than an individual, the trustee of the trust would file Form 3520 to report the gift. As a trust receiving large sums is more common, it is less likely to be scrutinized than if an individual were to receive the large gift.

6. U.S. persons receiving distributions from or controlling foreign trusts often face unfavorable or even punitive U.S. income tax consequences. As such, Wealth Creators seeking to immigrate the U.S. should consider unwinding their non-U.S. trusts in favor of U.S. trusts. Even Wealth Creators who are not personally seeking to immigrate to the U.S. but have U.S. descendants should consider shifting their assets into U.S. trusts, as they are generally more protective of U.S. descendants both from an asset protection perspective and from a U.S. tax perspective. When structured properly, moving assets into a U.S. trust can lead to (1) a clearer wealth transfer structure, (2) preferable tax treatment, (3) stronger asset protection and (4) lower ongoing maintenance costs (relating to both Trustee fees and accounting and disclosure requirements).