專業叢書

U.S. Trust and Estate Planning 美國信託規劃實務(英文部分)

Chapter 4 Relevant U.S. Tax Forms for U.S. Trusts & Individuals

While the beginning of this book focused primarily on the utilization of U.S.-based dynasty trusts, this chapter focuses primarily on the various tax filing requirements for cross-border families and entities controlled by them. Specifically, this book briefly describes each of the tax forms we find relevant for cross-border families.

While the beginning of this book focused primarily on the utilization of U.S.-based dynasty trusts, this chapter focuses primarily on the various tax filing requirements for cross-border families and entities controlled by them. Specifically, this book briefly describes each of the tax forms we find relevant for cross-border families.

The U.S. imposes various obligations on many entities it has varying levels of jurisdiction over. These obligations are generally mandated by laws passed by the U.S. Congress and operationally carried out by U.S. Department of The Treasury (“USDT”). The Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) is one of the many agencies that report to the USDT.

The descriptions that follow are for purely education purposes and is not meant to be and should not be used as a guide for tax filing purposes. Clients that must complete one or more of the following forms should engage professional CPAs and licensed attorneys for their unique tax filing and estate planning needs.

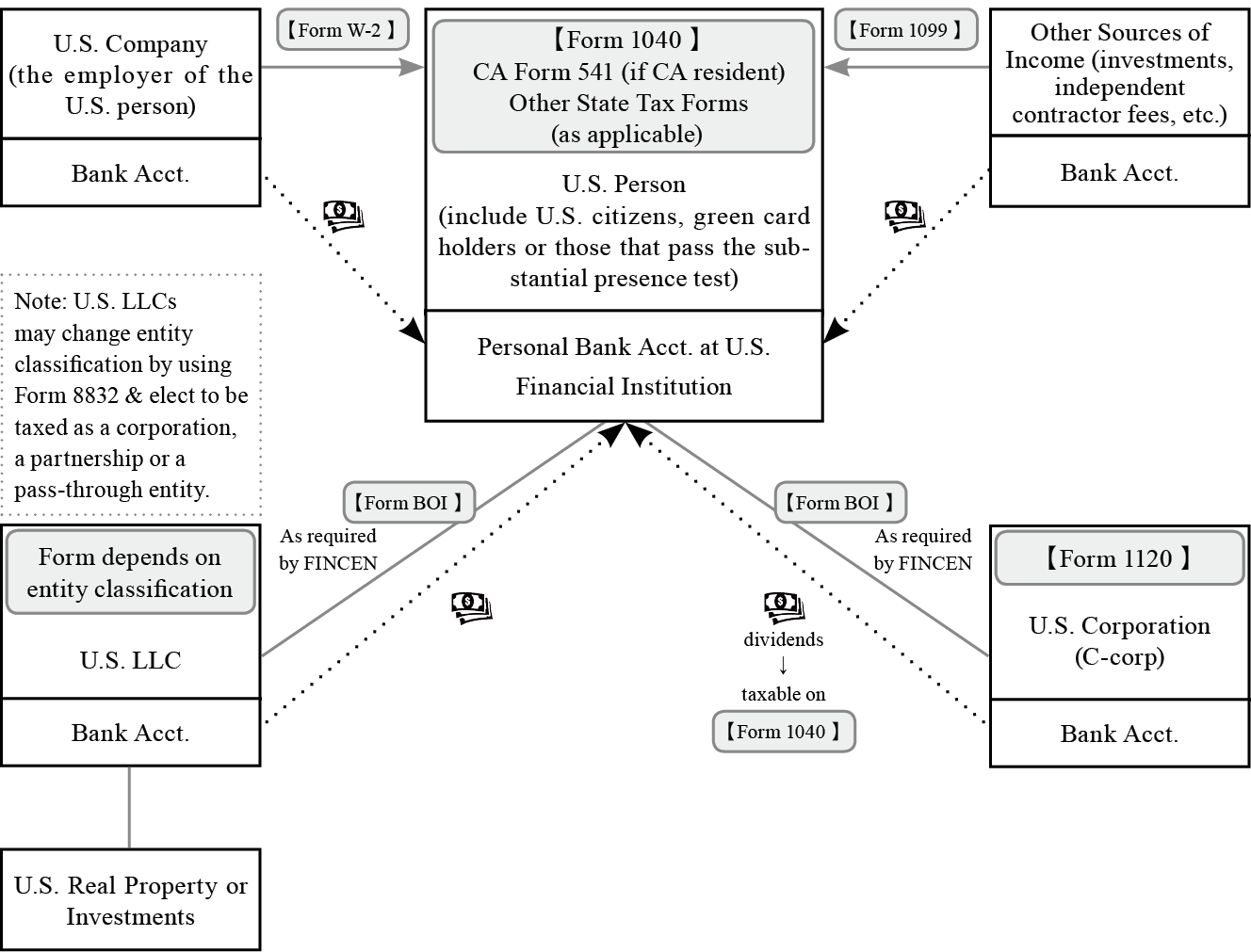

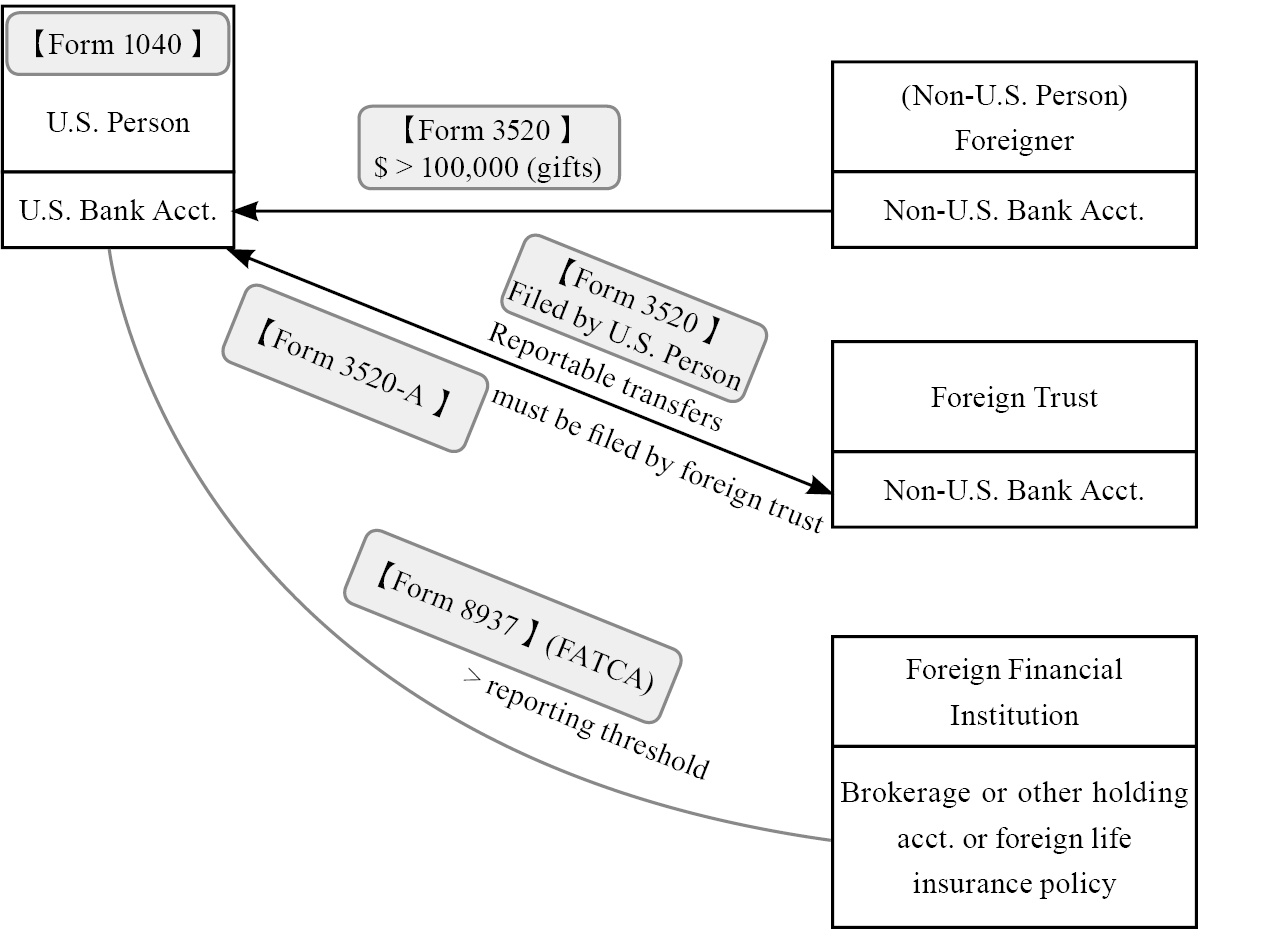

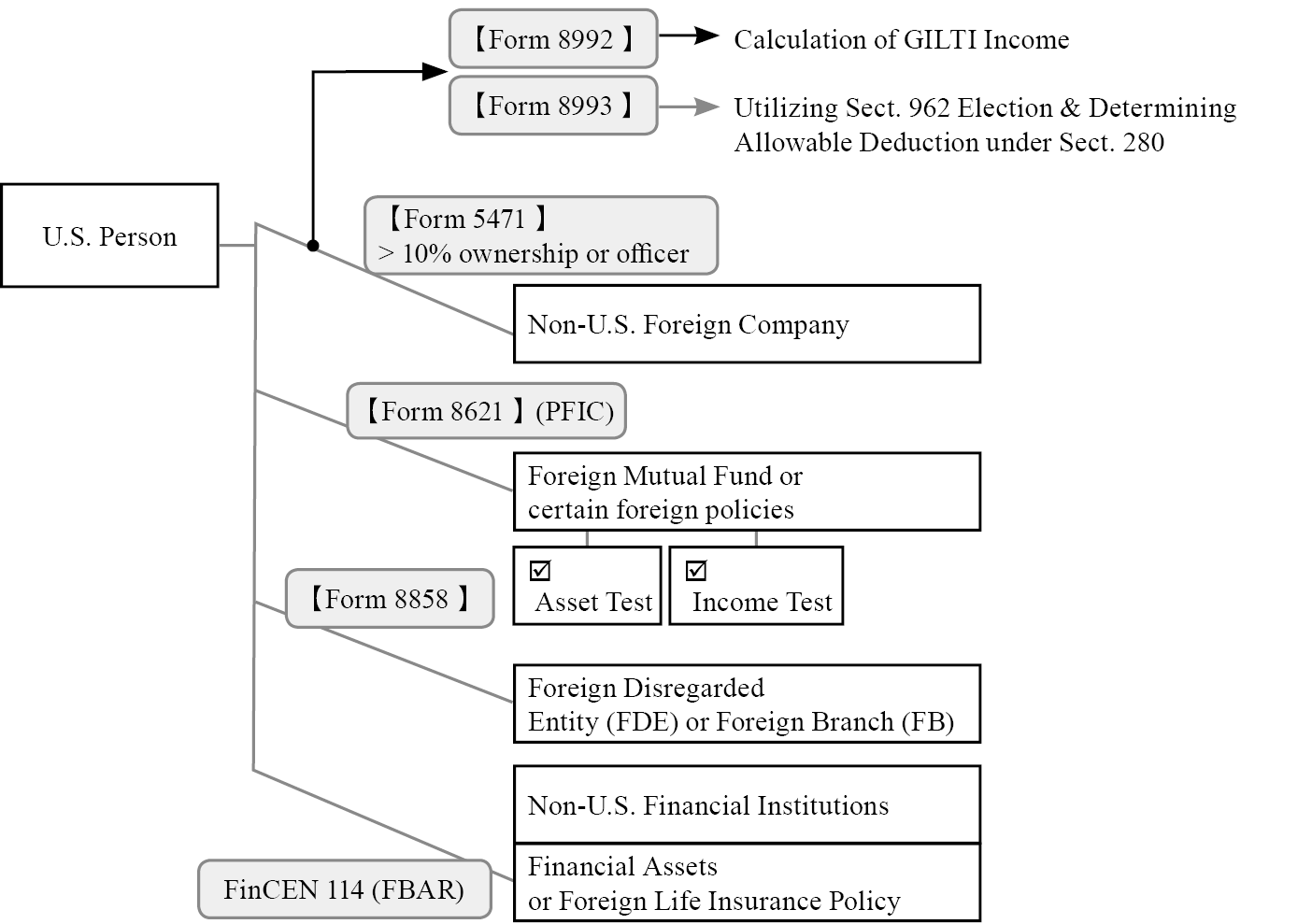

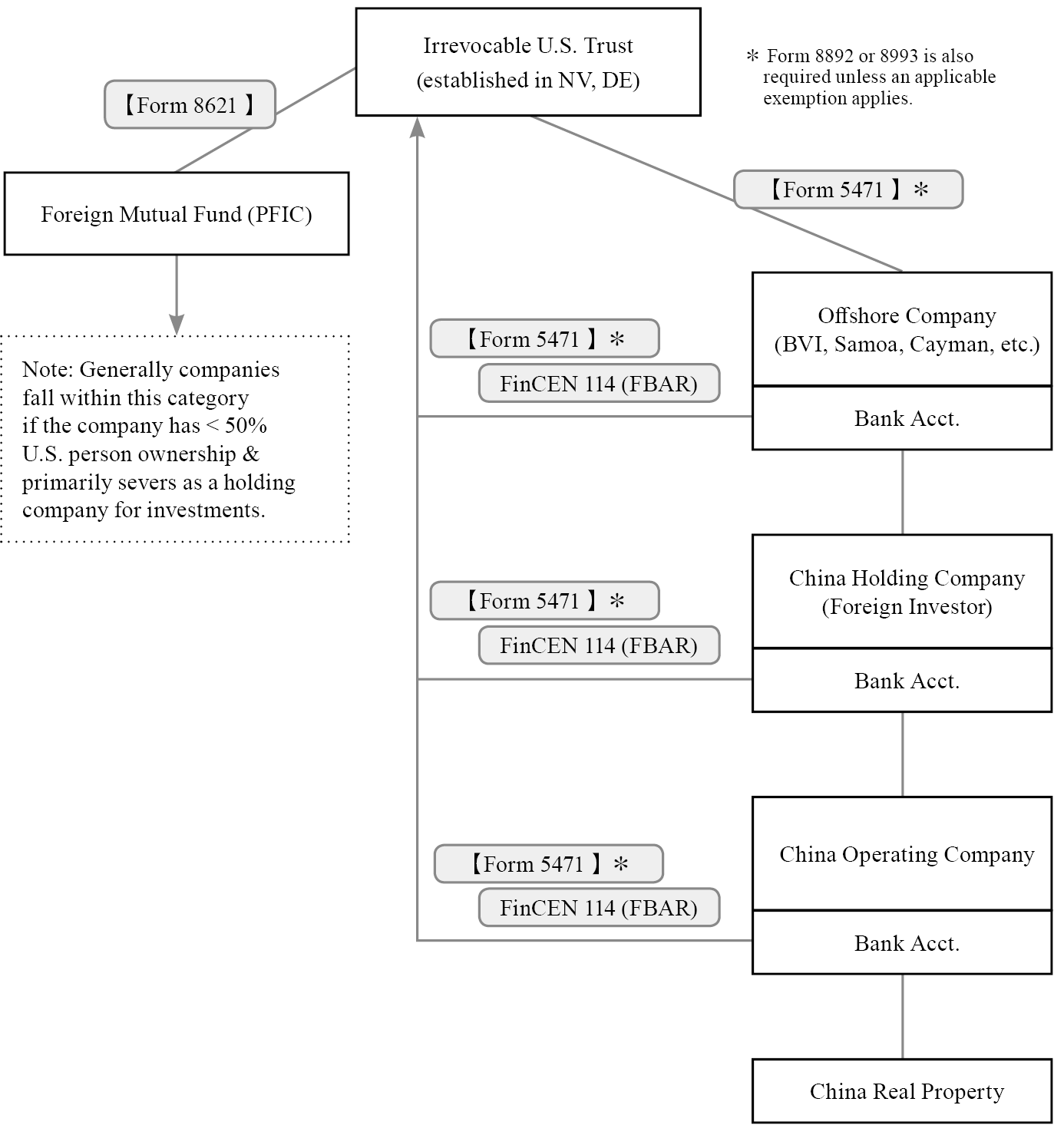

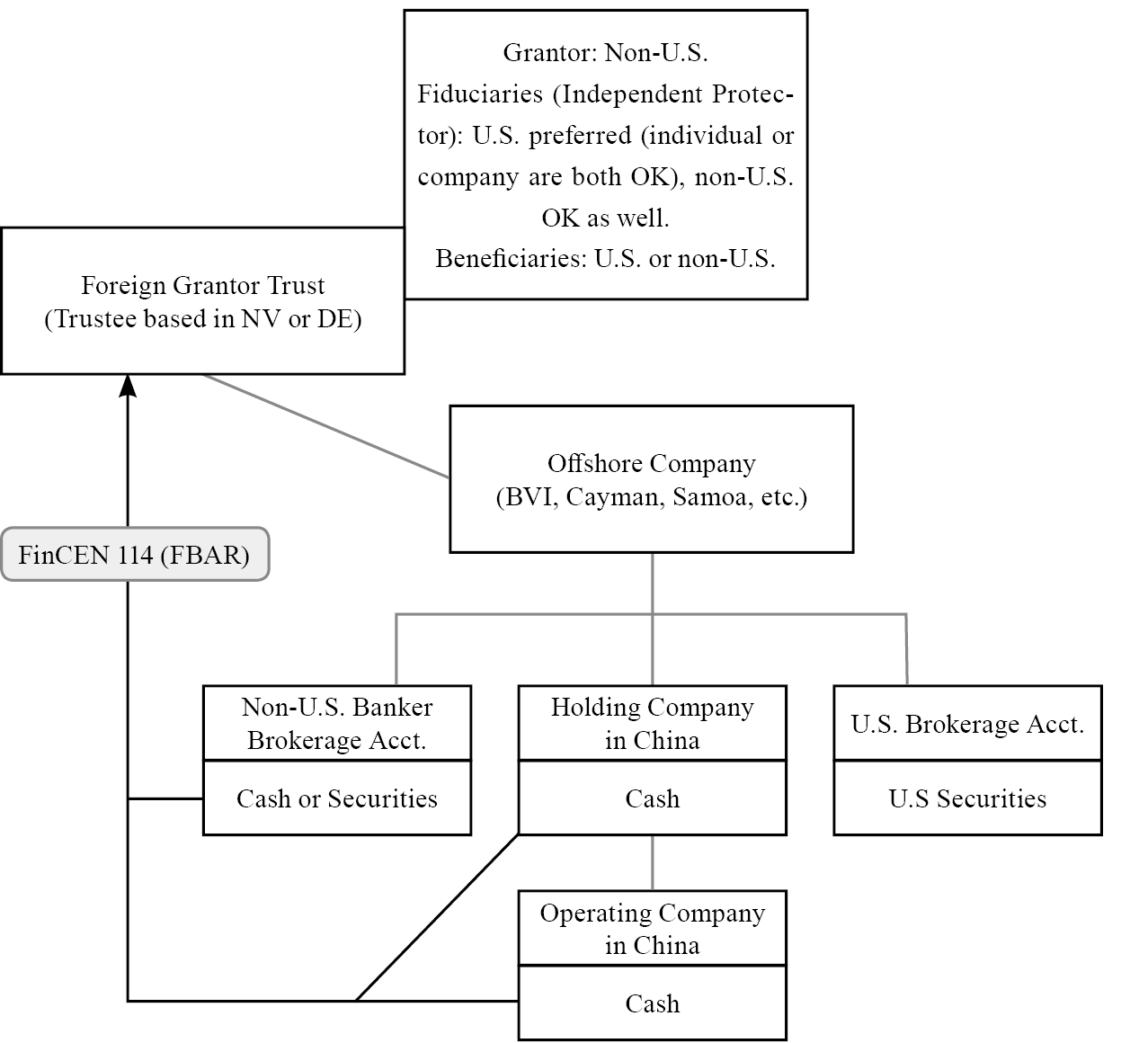

In our experience, cross-border families often must file one or more of the following forms. The following charts illustrate which forms could potentially be relevant for which taxpayers; please note that this is not an exhaustive list of the disclosures required of each individual within but rather an illustration of how and when each form could be used.

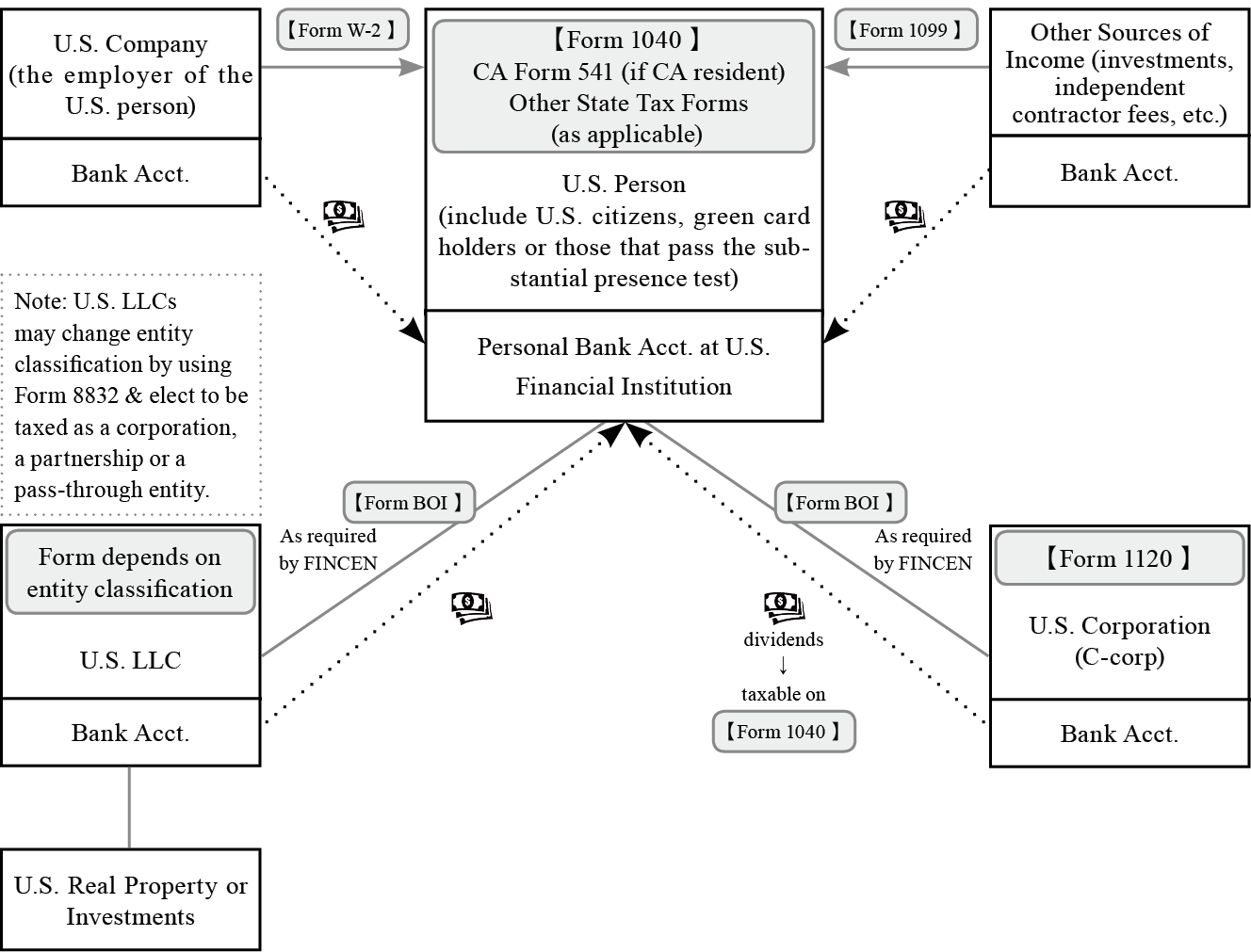

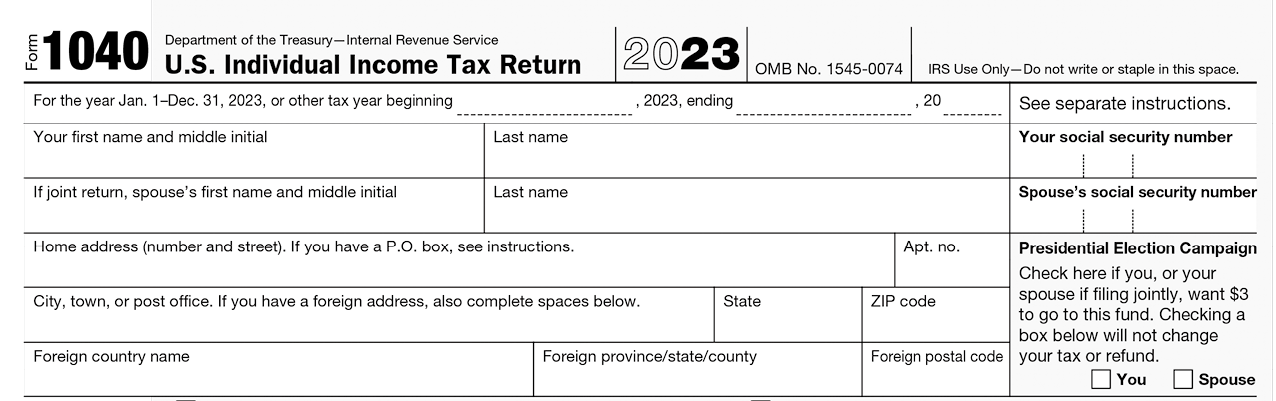

U.S. taxpayers generally report income from various sources on the Form 1040.

U.S. person owning domestic assets

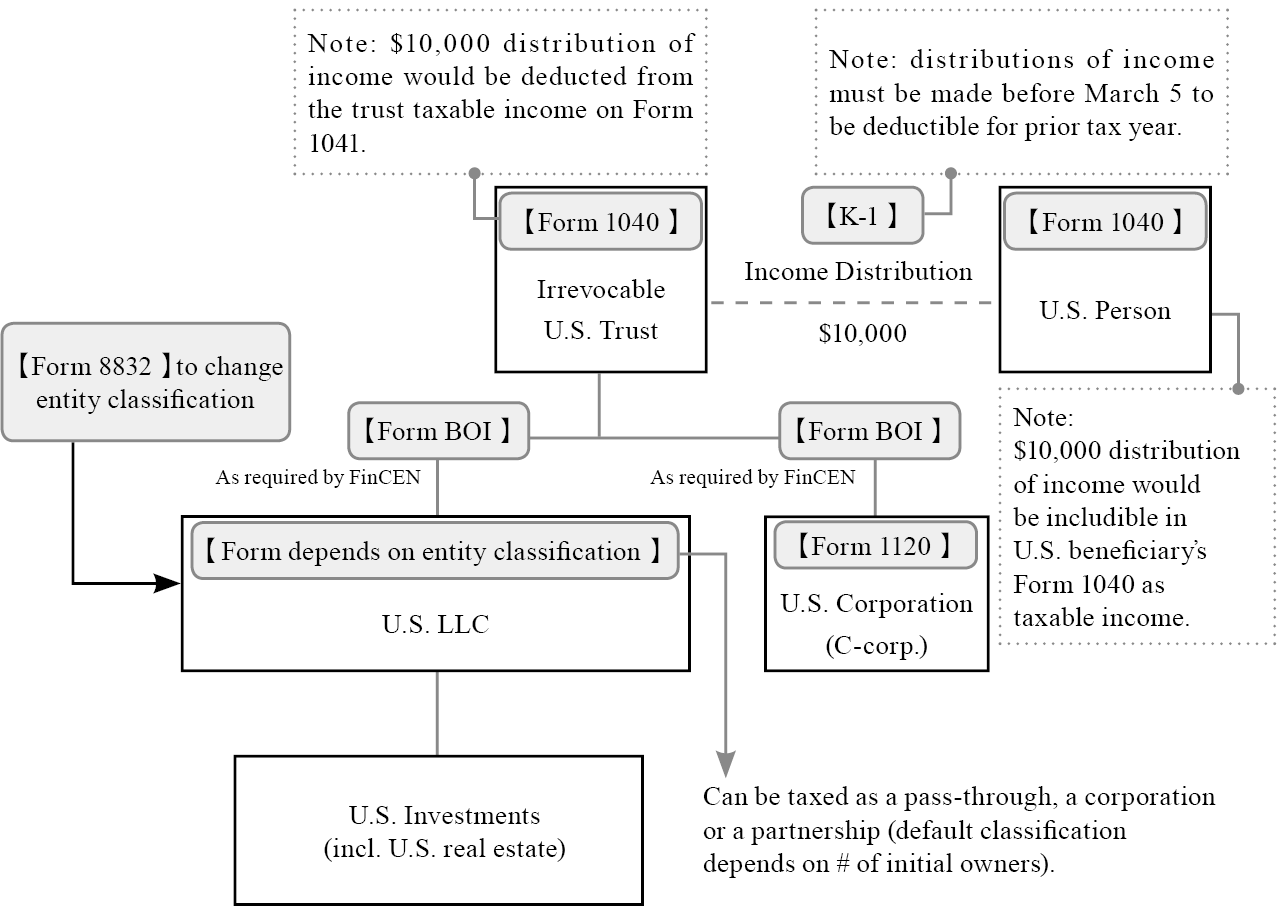

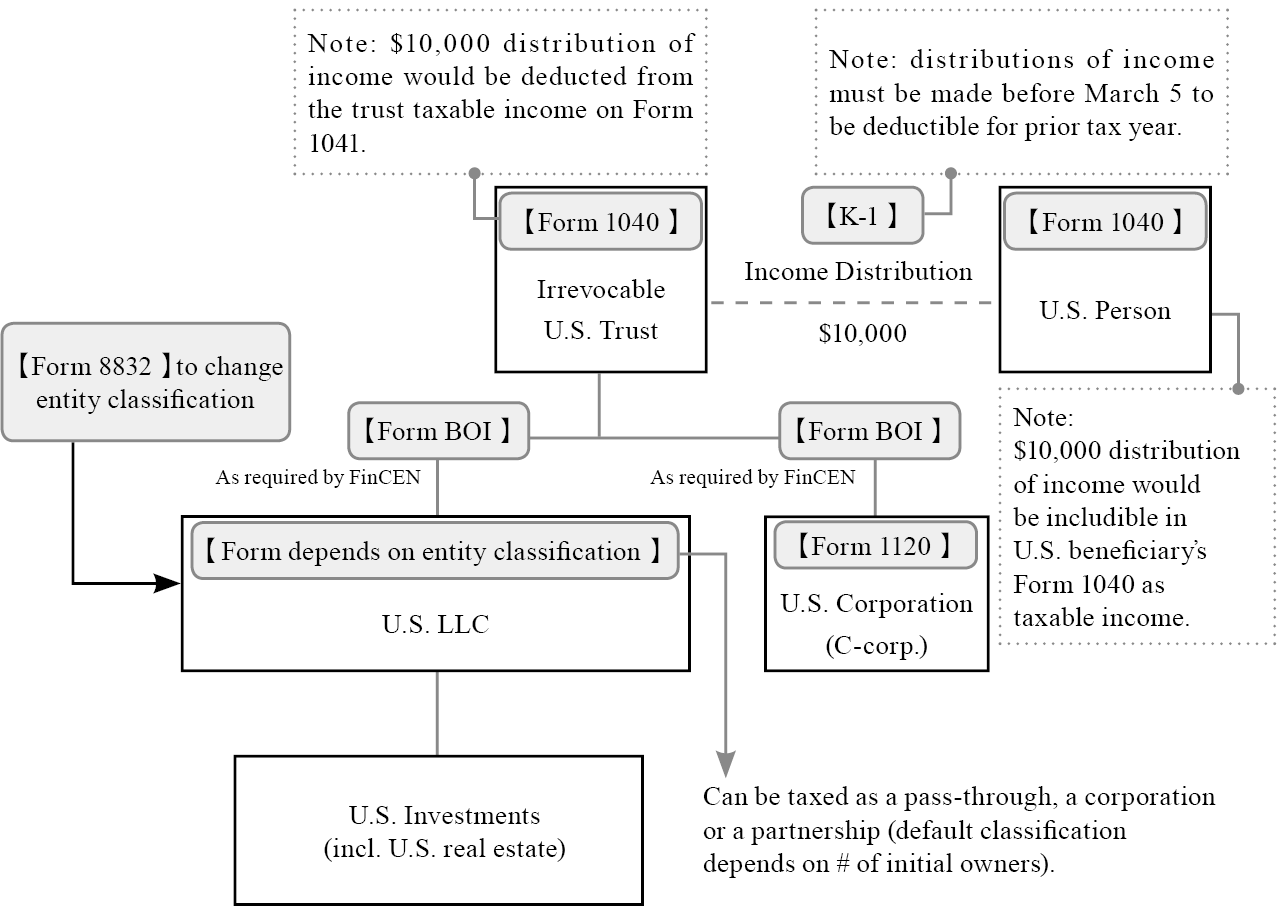

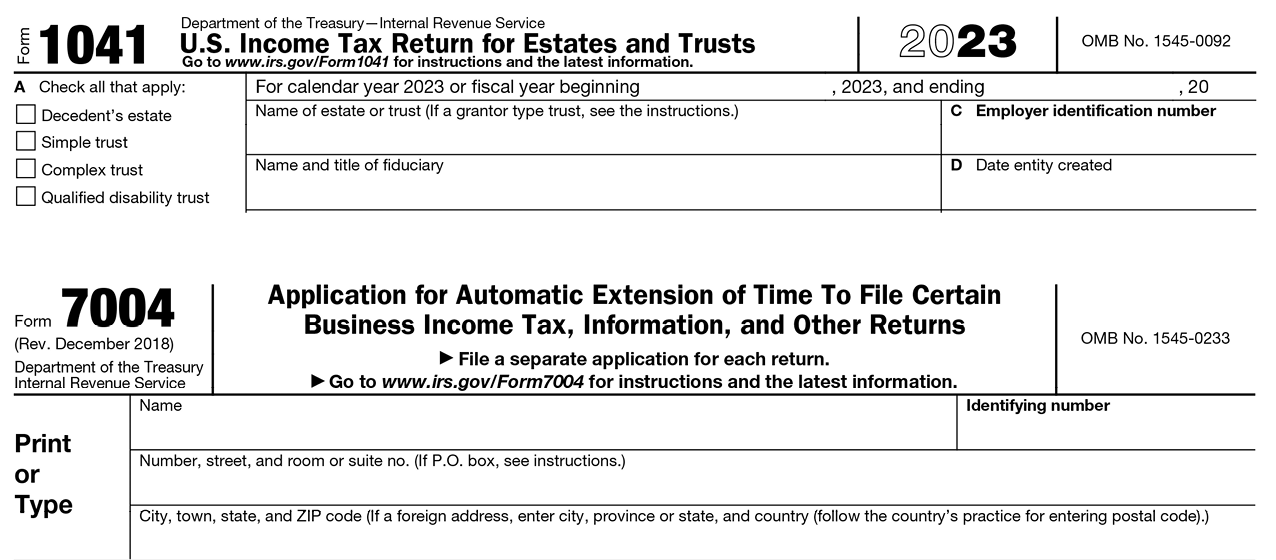

U.S. irrevocable trusts are generally subject to many of the same requirements as U.S. persons are subject to; however, trusts must complete a Form 1041 rather than a Form 1040.

U.S. Irrevocable Trust holding domestic assets

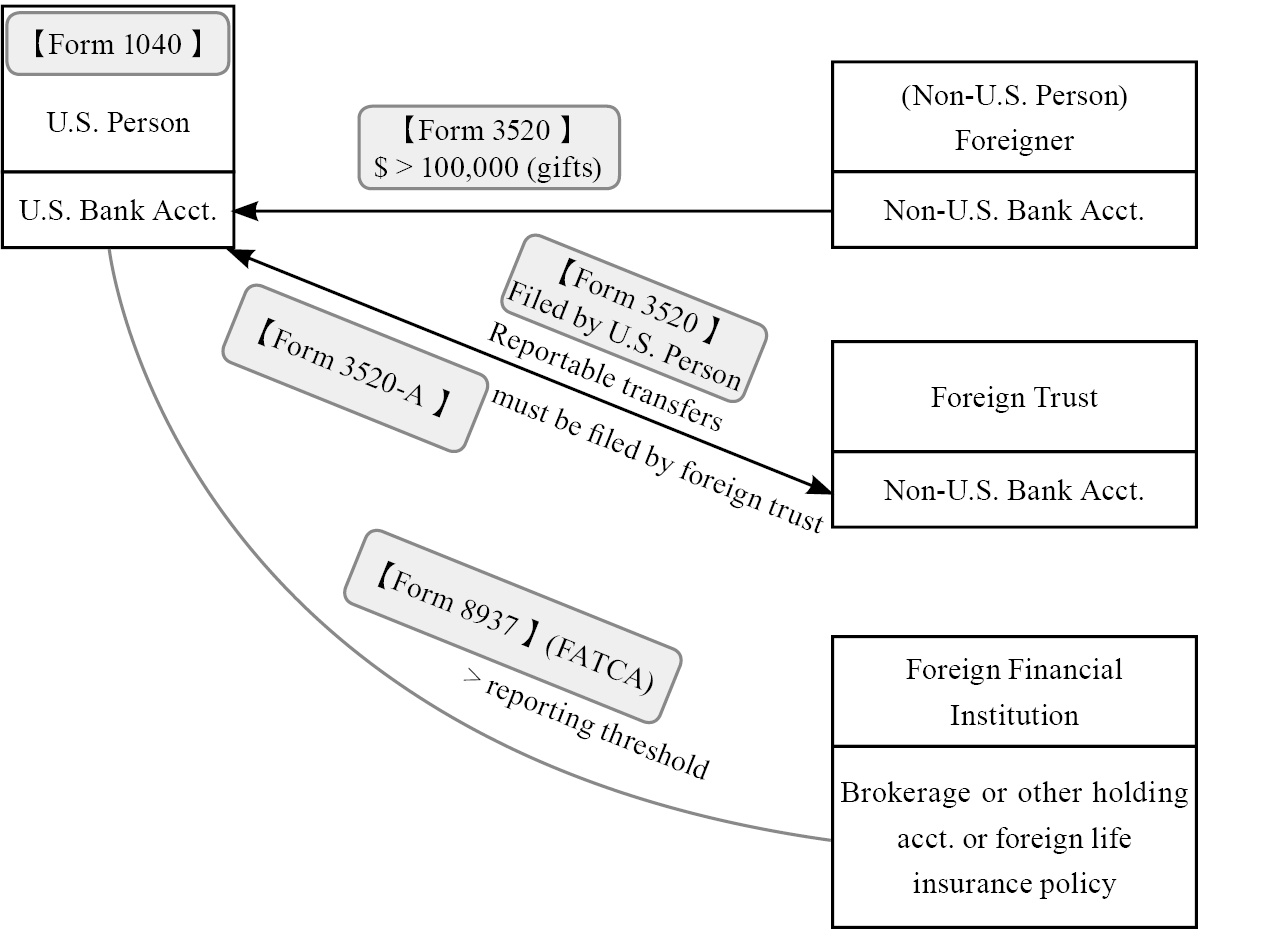

U.S. persons who own assets overseas are generally subject to U.S. taxation on their worldwide income. In addition, they may face certain disclosure requirements when receiving gifts from non-U.S. persons or trusts.

The following two charts include certain forms that may be required of U.S. persons when they directly or indirectly own or receive assets outside of the U.S:

U.S. person owning foreign assets (Part I)

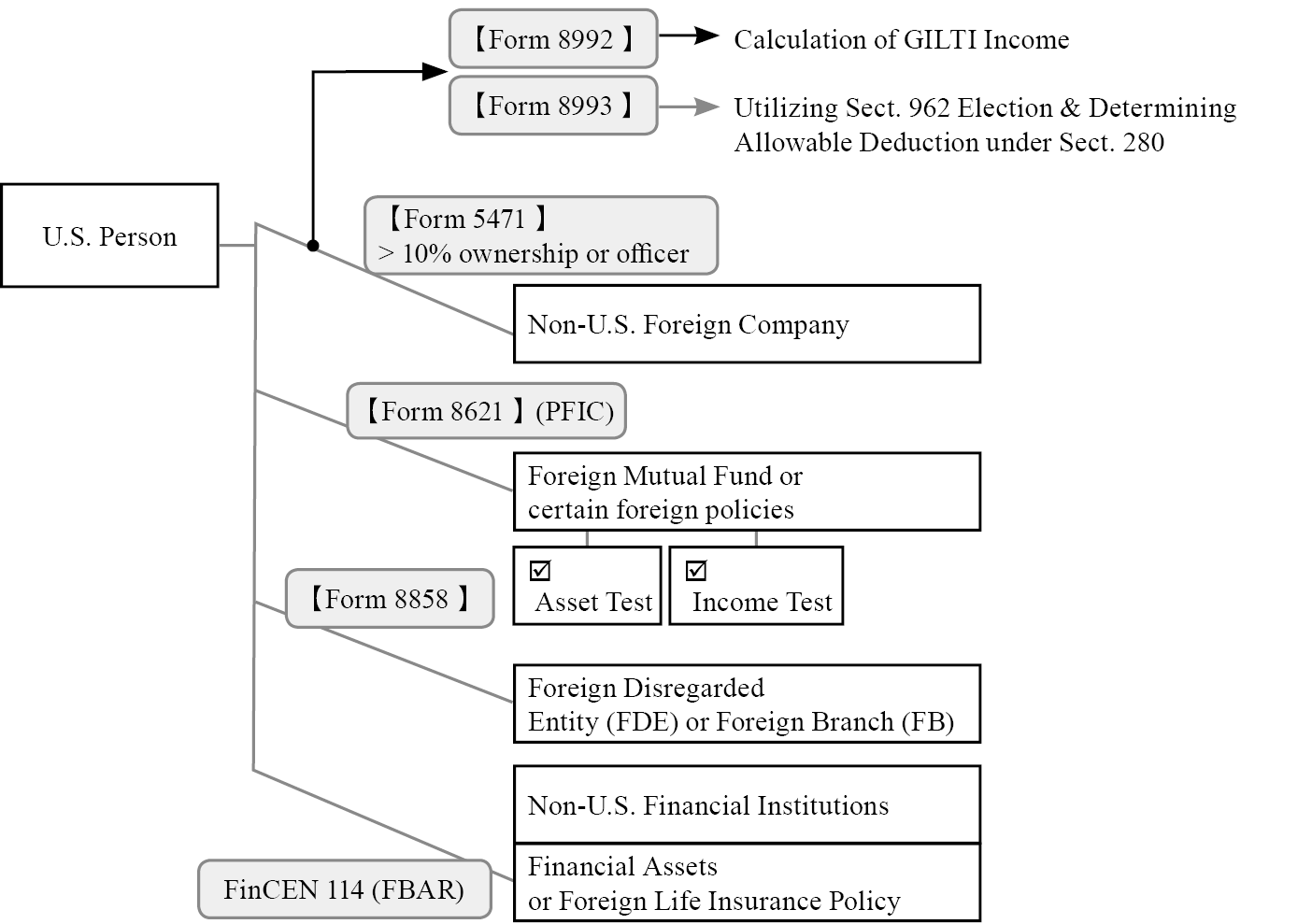

U.S. person owning foreign assets (Part II)

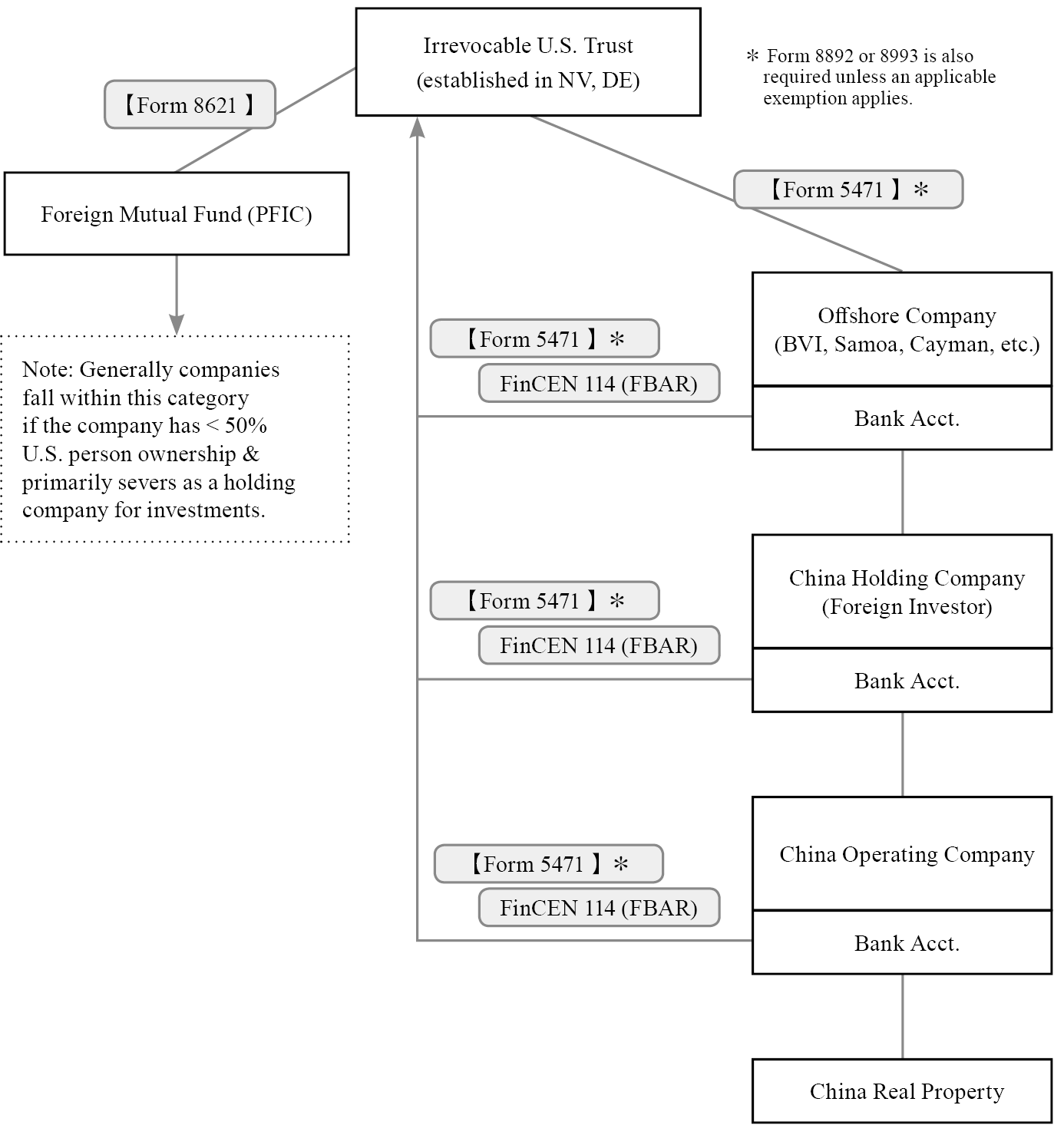

A U.S. irrevocable trust that owns assets overseas are also subject to a variety of requirements.

U.S. Irrevocable Trust holding foreign assets

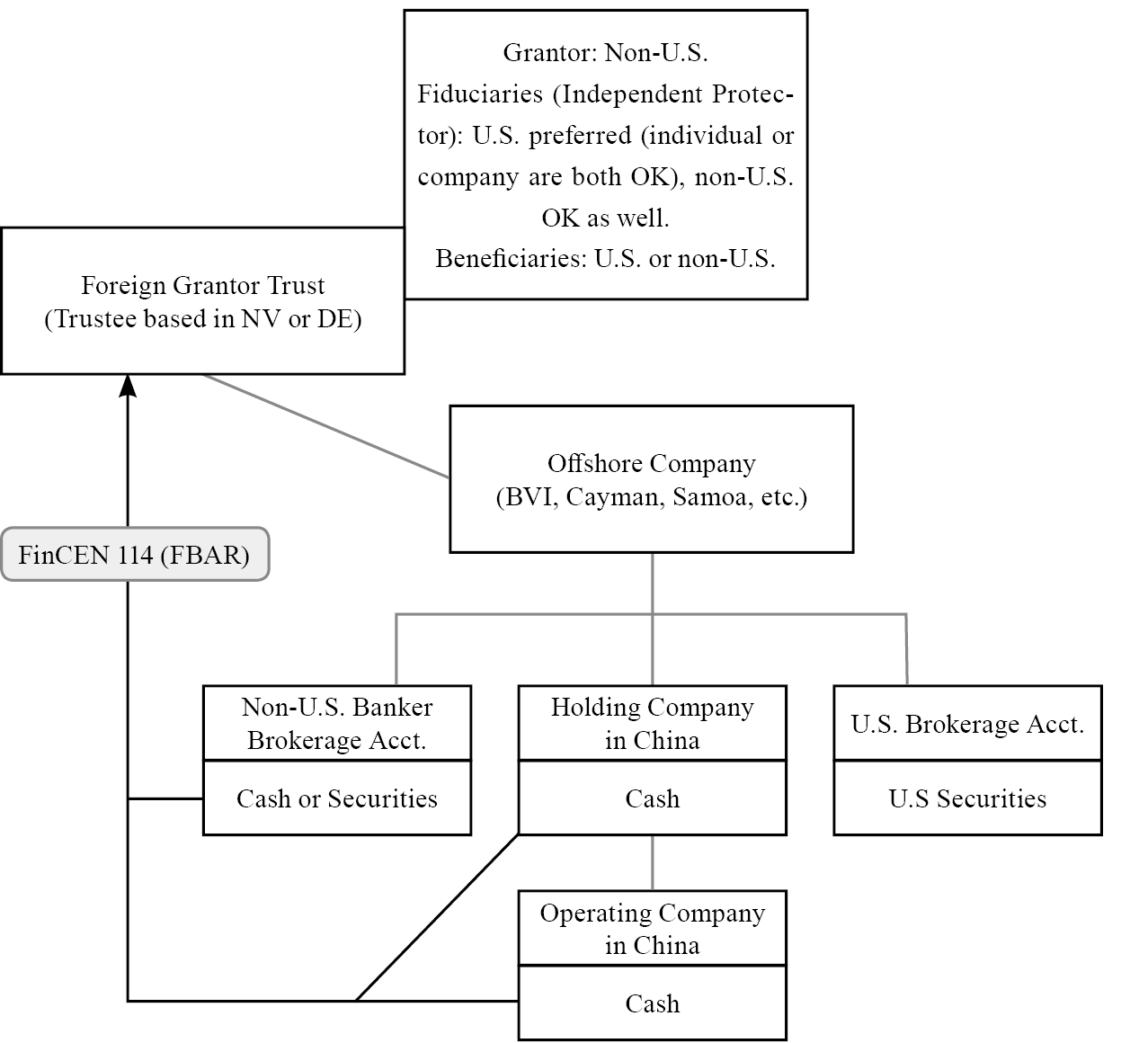

While foreign trusts (including foreign grantor trusts) that do not generate U.S.-sourced income generally does not file an income tax return, it is subject to FBAR requirements, which requires the completion of FINCEN Form 114.

FGT (Revocable Trust)

The U.S. imposes various obligations on many entities it has varying levels of jurisdiction over. These obligations are generally mandated by laws passed by the U.S. Congress and operationally carried out by U.S. Department of The Treasury (“USDT”). The Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) is one of the many agencies that report to the USDT.

The descriptions that follow are for purely education purposes and is not meant to be and should not be used as a guide for tax filing purposes. Clients that must complete one or more of the following forms should engage professional CPAs and licensed attorneys for their unique tax filing and estate planning needs.

In our experience, cross-border families often must file one or more of the following forms. The following charts illustrate which forms could potentially be relevant for which taxpayers; please note that this is not an exhaustive list of the disclosures required of each individual within but rather an illustration of how and when each form could be used.

U.S. taxpayers generally report income from various sources on the Form 1040.

U.S. person owning domestic assets

U.S. irrevocable trusts are generally subject to many of the same requirements as U.S. persons are subject to; however, trusts must complete a Form 1041 rather than a Form 1040.

U.S. Irrevocable Trust holding domestic assets

U.S. persons who own assets overseas are generally subject to U.S. taxation on their worldwide income. In addition, they may face certain disclosure requirements when receiving gifts from non-U.S. persons or trusts.

The following two charts include certain forms that may be required of U.S. persons when they directly or indirectly own or receive assets outside of the U.S:

U.S. person owning foreign assets (Part I)

U.S. person owning foreign assets (Part II)

A U.S. irrevocable trust that owns assets overseas are also subject to a variety of requirements.

U.S. Irrevocable Trust holding foreign assets

While foreign trusts (including foreign grantor trusts) that do not generate U.S.-sourced income generally does not file an income tax return, it is subject to FBAR requirements, which requires the completion of FINCEN Form 114.

FGT (Revocable Trust)

Individuals who are U.S. citizens or resident aliens (non-Citizens who are residents for income tax purposes) generally must file an income tax return in their individual capacity (Form 1040). Individuals may be exempt from filing a Form 1040 if their gross income is less than certain thresholds as set forth by the IRS ($13,850 for single filers under 65 and $27,700 for married filers under 65 filing joint returns in 2023).

Form 1040 is due on April 15 of each year. An automatic filing extension to October 15 is generally applicable if Form 4868 is filed by April 15. The U.S. imposes higher income taxes on those with higher incomes up to a maximum Federal income tax rate of 37%. Specific tax rates depend on the status of the filer and any tax deductions or credits the filer is applicable for.

When preparing your Form 1040 filing, your tax preparer will often request that you provide certain information regarding your income including but not limited to any Form 1099s or W-2s that you have received. When a U.S. beneficiary receives a distribution, the income from the K-1 needs to be filled on Form 1040 and attached Schedule E. These forms inform the tax preparer of income you’ve received over the course of the previous calendar year.

A gift is subject to U.S. gift tax when made by a foreign donor (who would pay the tax) only if it is a gift of tangible personal property physically situated in the United States. However, even if a gift does not give rise to U.S. federal income tax or gift tax liability, if a U.S. person receives gifts from a foreign person, the U.S. person may be required to report such gifts.

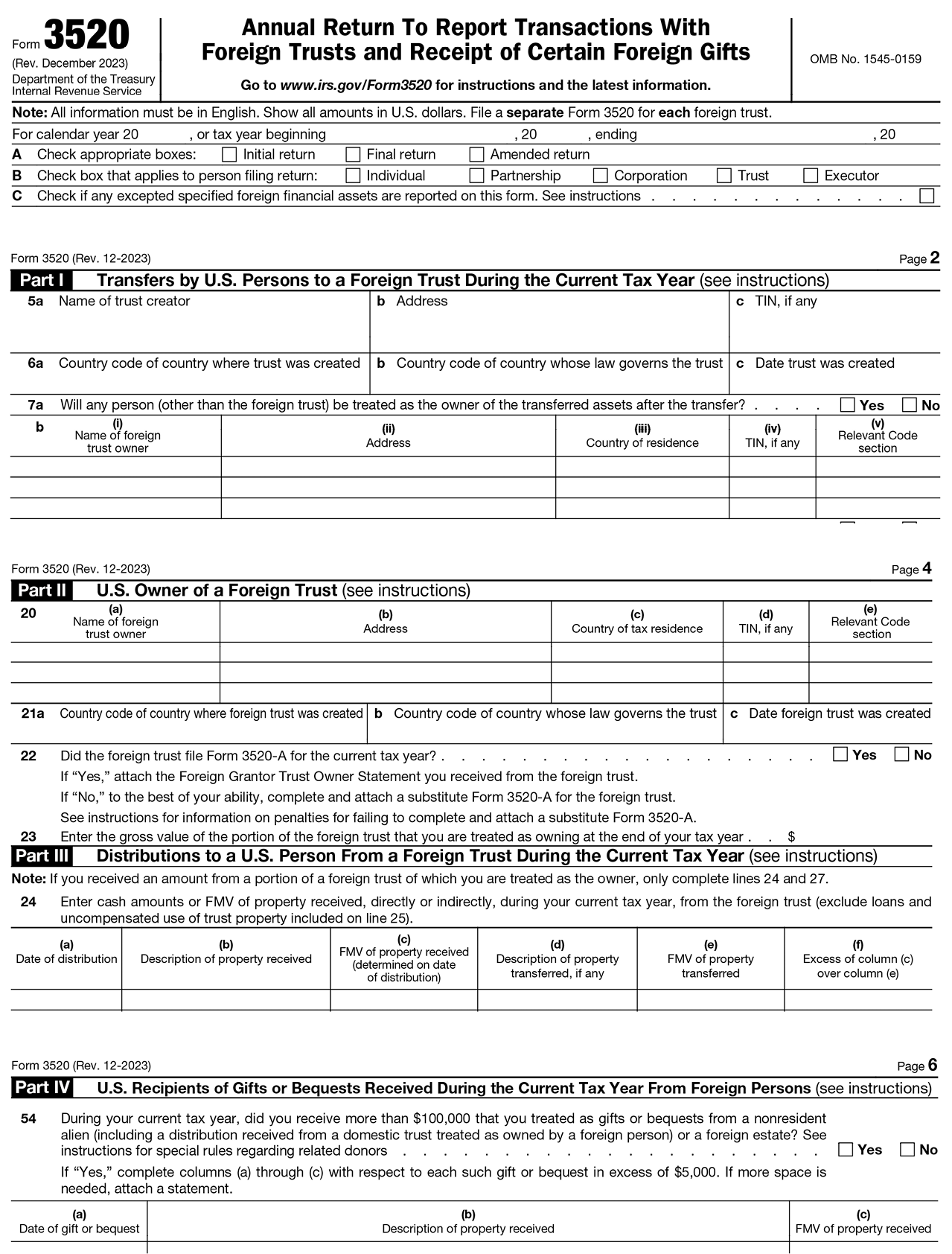

More specifically, if the value of the aggregate foreign gifts received by a U.S. person during any tax year exceeds a certain threshold, the U.S. person is required to report certain information on such foreign gifts on Form 3520. For this purpose, a “foreign gift” is any amount received from a foreign person that the recipient treats as a gift or bequest. Thus, foreign gifts could include gifts of cash or personal property (such as cars, art, or furniture), as well as gifts of residential real property. In addition, foreign gifts could include payments made by the foreign person on behalf of the U.S. person.

With respect to the threshold, a U.S. person must report the receipt of gifts from a foreign individual or foreign estate if the aggregate amount of gifts from that foreign individual or foreign estate exceeds $100,000 during the tax year. Form 3520 further requires that the U.S. person separately identify each gift in excess of $5,000 by providing the date of the gift, a description of the property received, and the fair market value (FMV) of the property received.

For individuals receiving gifts from non-U.S. persons totaling more than $100,000 or Foreign Trusts, Form 3520 is required. Certain trusts may also be required to file Form 3520 upon receiving gifts from non-U.S. persons.

Since the penalties for failing to file Form 3520 are especially heavy, you should pay special attention to ensure that the form is filed both timely and accurately. Those who fail to report foreign gifts may be liable for up to 25% of the amounts received. Penalties for individuals who received distributions from Foreign Trusts may be liable for 35% of the amounts received.

Fiduciaries of U.S. trusts and estates which meet the following criteria must file Form 1041 to report income:

(1) Any taxable income for the tax year;

(2) Gross income of $600 or more (regardless of taxable income);

(3) A beneficiary who is a nonresident alien.

The form is due on April 15 of each year. An automatic filing extension to September 30 is generally applicable if Form 7004 is filed by April 15. You must provide Schedule K-1 (Form 1041), on or before the day you are required to file Form 1041, to each beneficiary who receives a distribution of property or an allocation of an item of the estate.

Irrevocable trusts established by non-U.S. persons are generally treated as non-grantor trusts, with certain exceptions. Non-grantor trusts generally pay income tax on any income generated by income not distributed to the trust’s beneficiaries. Income distributed to trust beneficiaries is typically recorded on a Form K-1 and provided to the beneficiaries’ tax preparers. Beneficiaries who receive income generally must include income received from the trust on their Form 1040. Distributions within the first 65 days of the year are generally treated as distributions for the previous calendar year. As such, qualified tax professionals often give clients’ an estimate of income taxes owed at the beginning of the year to give the clients’ a chance to decide if they would like to distribute to the trusts’ beneficiaries.

A trust is a grantor trust if the grantor retains certain powers or ownership benefits. Generally, a revocable trust settled by a non-U.S. person is treated as a foreign grantor trust. In general, a grantor trust is ignored for income tax purposes and all of the income, deductions, etc., are treated as belonging directly to the grantor. This also applies to any portion of a trust that is treated as a grantor trust. If the entire trust is a grantor trust, fill in only the entity information of Form 1041. Don’t show any dollar amounts on the form itself; show dollar amounts only on an attachment to the form. Don’t use Schedule K-1 (Form 1041) as the attachment.

Note: For a detailed explanation of the Form 3520, please refer to the previous section, which discusses the Form 1040. A Form 3520 may be required to be filed with the Form 1041 if a trust receives a gift from a non-U.S. donor (certain exceptions apply).

Late Filing Penalty: The law provides a penalty of 5% of the tax due for each month, or part of a month, for which a return isn’t filed up to a maximum of 25% of the tax due (15% for each month, or part of a month, up to a maximum of 75% if the failure to file is fraudulent). The penalty won’t be imposed if you can show that the failure to file on time was due to reasonable cause. If you receive a notice about penalty and interest after you file this return, send us an explanation and we will determine if you meet reasonable-cause criteria.

Late Payment Penalty: Generally, the penalty for not paying tax when due is 1/2 of 1% of the unpaid amount for each month or part of a month it remains unpaid. The maximum penalty is 25% of the unpaid amount. The penalty applies to any unpaid tax on the return. Any penalty is in addition to interest charges on late payments.

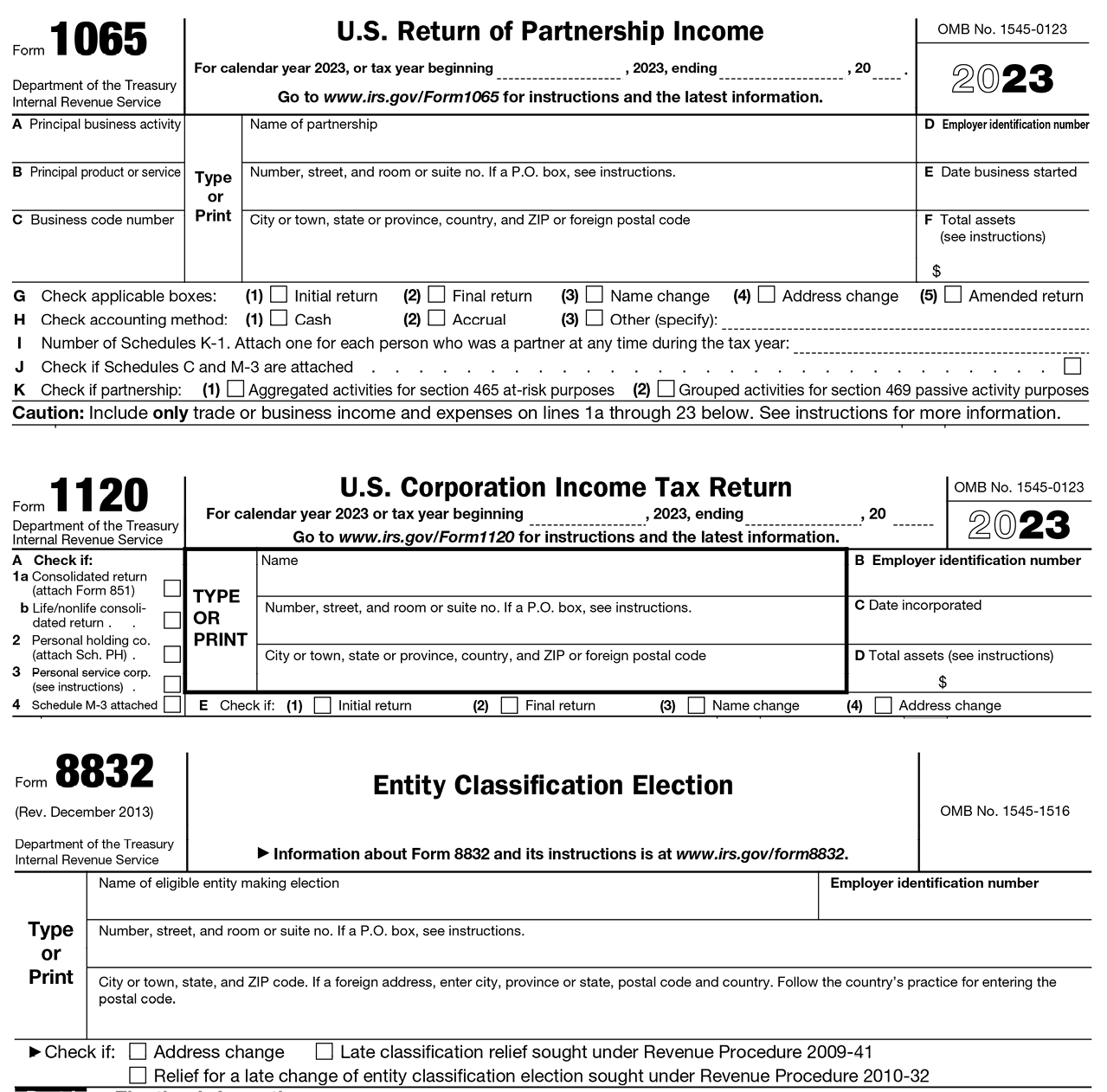

Form 8832 categorizes an eligible entity (typically, a U.S. LLC) as either a corporation, a partnership, or a disregarded entity for federal tax purposes.

- When an LLC is categorized as a partnership, it generally must file Form 1065. This is the “default” state for U.S. LLCs with more than one owner when it was formed under state law.

- When an LLC is categorized as a disregarded entity, its income is includible in the income tax form filed by the company’s owner. This is the “default” state for U.S. LLCs with a single owner when it was formed under state law.

- When an LLC is categorized as a corporation, it generally must file Form 1120. This tax treatment is generally only eligible if a LLC has filed Form 8832 to elect to be treated as an association taxable as a corporation.

An eligible entity uses Form 8832 to elect how it will be classified for federal tax purposes, as a corporation, a partnership, or an entity disregarded as separate from its owner. An eligible entity is classified for federal tax purposes under the default rules described below unless it files Form 8832 or Form 2553. The IRS will use the information entered on this form to establish the entity’s filing and reporting requirements for federal tax purposes.

An LLC is an entity formed under state law by filing articles of organization as an LLC. Unlike a partnership, none of the members of an LLC are personally liable for its debts. An LLC may be classified for federal income tax purposes as a partnership, a corporation, or an entity disregarded as an entity separate from its owner by applying the rules in Regulations section 301.7701-3.

Form 1065 is an information return used to report the income, gains, losses, deductions, credits, and other information from the operation of a partnership. Generally, a partnership doesn’t pay tax on its income but passes through any profits or losses to its partners. Partners must include partnership items on their tax or information returns.

Form 1120 is the U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return used to report the income, gains, losses, deductions, credits, and to figure the income tax liability of a corporation. Unless exempt under section 501, all domestic corporations (including corporations in bankruptcy) must file an income tax return whether or not they have taxable income. Domestic corporations must file Form 1120.

Note: When owners of a foreign corporation agree to file an entity classification election (Form 8832) to treat the foreign company as a partnership for U.S. tax purposes, the election would trigger a deemed liquidation of the corporation for U.S. federal tax purposes on the day immediately preceding the effective date of the election. In a foreign grantor trust structure, a timely filed Form 8832 could increase the outside cost basis of an offshore company held by the trust prior to the grantor’s death without triggering U.S. income taxes. A subsequent sale of those assets (shares in the offshore company) could be fully taxable outside the U.S.; however, within the U.S., it would be taxable only for appreciation of the offshore company that materializes after the grantor’s death. Proper application and use of the “check the box” election (Form 8832) for eligible taxpayers could effectively reduce U.S. income tax.

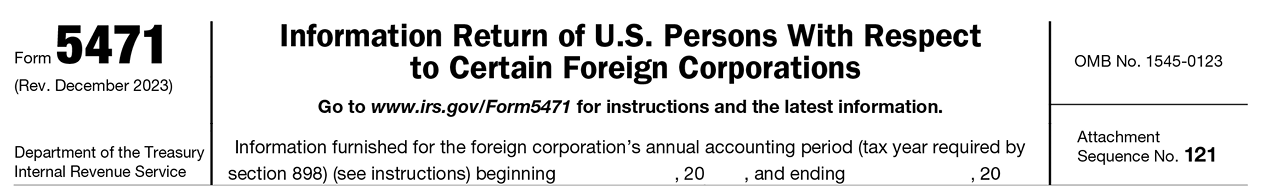

Form 5471 is used by certain U.S. persons who are officers, directors, or shareholders in certain foreign corporations. The form and schedules are used to satisfy the reporting requirements of sections 6038 and 6046, and the related regulations. Generally, if you own or control a foreign company, directly or indirectly, you may be required to file Form 5471 and should consult with your U.S. accountant to determine how to appropriately satisfy your tax and disclosure obligations.

A U.S. shareholder for these purposes is a U.S. person that owns (directly, indirectly, or constructively) 10% or more of the total combined voting power or value of shares of all classes of a foreign corporation’s stock. A CFC is any foreign corporation if more than 50% of the total combined voting power or value of shares of all classes of stock of the corporation is owned by U.S. shareholders on any day during the foreign corporation’s tax year. A U.S. shareholder of a CFC is required to include in gross income on a current basis their pro rata share of certain income earned by the CFC, regardless of whether they receive a distribution. An SFC is a CFC or any foreign corporation whose shares (at least 10%) are held by a U.S. person, unless it is otherwise categorized as a PFIC.

A controlled foreign corporation (CFC) that is not a foreign insurance company generally must satisfy the following requirements:

(1) A foreign company formed in a foreign country that is classified as a foreign corporation for U.S. purposes:

-

- Mandatory per se foreign corporation on the IRS list. See Form 8832 instructions.

- By default if all owners have limited liability

- By election on Form 8832 entity classification election for certain foreign eligible entities

(2) More than 50% of the vote or value is owned by U.S. shareholder who each own at least 10% of the vote or value.

(3) Direct, indirect, and constructive ownership percentages are taken into account under I.R.C. §§ 958(a) and (b) attribution rules to determine if a foreign corporation is a CFC.

Generally, all U.S. persons described in Categories of Filers below must complete the schedules, statements, and/or other information. The word “generally” is used, as there are many rules, interpretations and exceptions that may apply to the Wealth Creator’s specific situation; thus, Wealth Creators and their families should defer to their professional legal and tax advisors.

Category 1: A person who was a U.S. shareholder of an SFC at any time during the SFC’s tax year ending with or within the U.S. shareholder’s tax year and who owned stock on the last day in that year in which the foreign corporation was an SFC.

Category 2: A U.S. person who is an officer or director of a foreign corporation in which a U.S. person has acquired (in one or more transactions): (1) 10% stock ownership (by vote or value) with respect to the foreign corporation, or (2) an additional 10% or more of the outstanding stock (by vote or value) of the foreign corporation.

Category 3: This category includes:

-

- A U.S. person who acquires stock in a foreign corporation that, when added to any stock owned on the date of acquisition, meets the 10% ownership threshold (by vote or value) with respect to the foreign corporation.

- A U.S. person who acquires stock that, without regard to stock already owned on the date of acquisition, meets the 10% ownership threshold (by vote or value) with respect to the foreign corporation.

- A person who is treated as a U.S. shareholder of a captive insurance company under Sec. 953(c) with respect to a foreign corporation.

- A person who becomes a U.S. person while meeting the 10% ownership threshold (by vote or value) with respect to the foreign corporation.

- A U.S. person who disposes of sufficient stock in the foreign corporation to reduce their interest to less than the 10% ownership threshold.

- A U.S person who owns at least 10% of the corporation (by vote or value) when the corporation is reorganized.

Category 4: A U.S. person who had control (i.e., ownership of stock possessing either more than 50% of the total combined voting power or value of shares of all classes of stock) of a foreign corporation during the annual accounting period of the foreign corporation.

Category 5: A U.S. person who was a U.S. shareholder that owned stock in a foreign corporation that was a CFC at any time during the foreign corporation’s tax year ending with or within the U.S. shareholder’s tax year, and who owned that stock on the last day in that year in which the foreign corporation was a CFC.

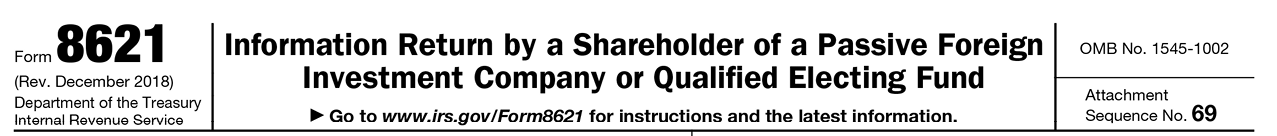

A U.S. person with a direct or indirect interest in a Passive Foreign Investment Company (“PFIC”) may be required to file Form 8621. A foreign corporation is a PFIC if it meets either a passive income test or a passive asset test.

Under the income test, a foreign corporation is treated as a PFIC if 75 percent or more of its gross income fits within the definition of “passive income”, which generally includes dividends, interest, royalties, rents, and annuities; there are many other special rules for determining what income is included.

Under the asset test, a foreign corporation is treated as a PFIC if the average percentage of assets held by such corporation during the taxable year which produces passive income, or which are held for the production of passive income, is at least 50 percent.

A foreign mutual fund is a common example of a PFIC. U. S. persons that own PFIC interests may be subject to additional tax and interest charges with respect to PFIC earnings and distributions. There is no threshold ownership requirement with respect to the PFIC rules, and thus a U. S. person can be subject to the PFIC rules even if their ownership interest in the PFIC is very small. However, to the extent that a foreign corporation is both a PFIC and a CFC, a U.S. investor that is a U.S. shareholder of the foreign corporation is generally only subject to the CFC rules with respect to their interest in the foreign corporation.

A U.S. investor in a PFIC is subject to one of three alternative taxing regimes generally at the investor’s election:

(1) the excess distribution regime (the default regime);

(2) the “qualified electing fund”(QEF) regime; or

(3) the “mark-to-market” regime.

The specific information required on Form 8621 varies depending upon which PFIC taxing regime applies. Generally, a U.S. investor is required to file a Form 8621 if they:

(1) receive certain direct or indirect distributions from a PFIC;

(2) recognize a gain on a direct or indirect disposition of PFIC stock;

(3) are making certain elections with respect to the PFIC, including a QEF or mark-to-market election;

(4) are reporting information with respect to a QEF or mark-to market election; or

(5) are required to file an annual report with respect to a PFIC.

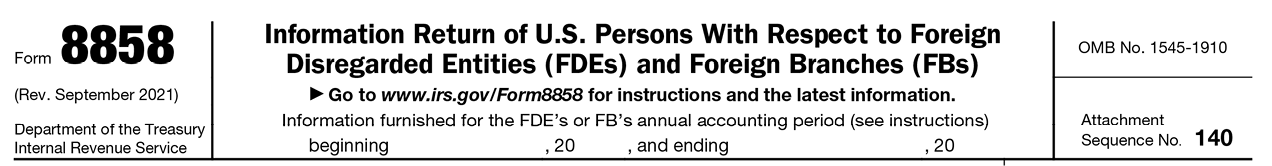

Form 8858 is used by certain U.S. persons that operate a Foreign Branch (“FB”) or own a Foreign Disregarded Entity (“FDE”) directly or, in certain circumstances, indirectly or constructively. The form and schedules are used to satisfy the reporting requirements of sections 6011, 6012, 6031, and 6038, and related regulations. Form 8858 reports certain information about the foreign disregarded entity, including information regarding the entity’s income, losses, earnings and profits, and income taxes paid.

An FB is defined in Regulations section 1.367(a)-6T(g). For purposes of filing a Form 8858, an FB also includes a qualified business unit (QBU) (as defined in Regulations section 1.989(a)-1(b)(2)(ii)) that is foreign.

An FDE is an entity that is not created or organized in the United States and that is disregarded as an entity separate from its owner for U.S. income tax purposes under Regulations sections 301.7701-2 and 301.7701-3. An eligible entity uses Form 8832 to elect how it will be classified for federal tax purposes. A copy of Form 8832 is generally attached to the entity’s federal tax return for the tax year of the election. The tax owner of the FDE is the person that is treated as owning the assets and liabilities of the FDE for purposes of U.S. income tax law.

The following U.S. persons that are tax owners of FDEs, operate an FB, or that own certain interests in tax owners of FDEs or FBs must file Form 8858 and Schedule M (Form 8858) :

Category 1: A U.S. person that is a tax owner of an FDE or operates an FB at any time during the U.S. person’s tax year or annual accounting period. Complete the entire Form 8858, including the separate Schedule M (Form 8858) and other schedules as required.

Category 2: A U.S. person that directly (or indirectly through a tier of FDEs) is a tax owner of an FDE or operates an FB. Complete the entire Form 8858, including the separate Schedule M (Form 8858).

Category 3: Certain U.S. persons that are required to file Form 5471 with respect to a CFC that is a tax owner of an FDE or operates an FB at any time during the CFC’s annual accounting period.

Category 4: Certain U.S. persons that are required to file Form 8865 with respect to a controlled foreign partnership (“CFP”) that is a tax owner of an FDE or operates an FB at any time during the CFP’s annual accounting period.

Category 5: Certain U.S. person that is a partner in a partnership that owns an FDE or operates an FB and applies section 987 to the activities of the FDE or FB. The U.S. person must complete the first page of the Form 8858 and Schedule C-1 for each FDE and FB of the partnership.

Category 6: Certain U.S. corporations (other than a RIC, a REIT, or an S corporation) that is a partner in a U.S. partnership, which checked box 11 on Schedules K-2 and K-3 (Form 1065). Even though the U.S. corporation is not the tax owner of the FDE and/or the FB, the U.S. corporation must complete lines 1 through 5 of the Form 8858, line 3 of Schedule G, and report its distributive share of the items on lines 10 through 13 of Schedule G for each FDE and FB of the U.S. partnership.

What are the penalties for the failure to file Form 8858 and Schedule M (Form 8858)?

A $10,000 penalty is imposed for each annual accounting period of each CFC or CFP for failure to furnish the required information within the time prescribed. If the information is not filed within 90 days after the IRS has mailed a notice of the failure to the U.S. person, an additional $10,000 penalty (per CFC or CFP) is charged for each 30-day period, or fraction thereof, during which the failure continues after the 90-day period has expired. The additional penalty is limited to a maximum of $50,000 for each failure.

Any person who fails to file or report all of the information required within the time prescribed will be subject to a reduction of 10% of the foreign taxes available for credit under sections 901 and 960. If the failure continues 90 days or more after the date the IRS mails notice of the failure to the U.S. person, an additional 5% reduction is made for each 3-month period during which the failure continues after the 90-day period has expired.

Criminal penalties. Criminal penalties under sections 7203, 7206, and 7207 may apply for failure to file the information required by section 6038.

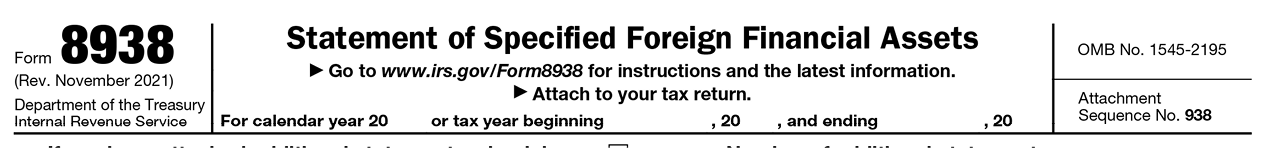

Unless an exception applies, you must file Form 8938 if you are a specified person (specified individual or a specified domestic entity) that has an interest in specified foreign financial assets and the value of those assets is more than the applicable reporting threshold. If you are required to file Form 8938, you must report the specified foreign financial assets in which you have an interest even if none of the assets affects your tax liability for the year. Typically, filed with the Form 1040 (for individuals) or Form 1041 (for domestic trusts).

You are a specified individual if you are one of the following.

(1) A U.S. citizen.

(2) A resident alien of the United States for any part of the tax year (green card or substantial presence).

(3) A nonresident alien who makes an election to be treated as a resident alien for purposes of filing a joint income tax return.

(4) A nonresident alien who is a bona fide resident of American Samoa or Puerto Rico.

You are a specified domestic entity if you are one of the following.

(1) A closely held domestic corporation that has at least 50% of its gross income from passive income.

(2) A closely held domestic corporation if at least 50% of its assets produce or are held for the production of passive income.

(3) A closely held domestic partnership that has at least 50% of its gross income from passive income.

(4) A closely held domestic partnership if at least 50% of its assets produce or are held for the production of passive income (see Passive income and Percentage of passive assets held by a corporation or partnership, later).

(5) A domestic trust described in section 7701(a)(30)(E) that has one or more specified persons (a specified individual or a specified domestic entity) as a current beneficiary.

A domestic corporation is closely held if, on the last day of the corporation’s tax year, a specified individual directly, indirectly, or constructively owns at least 80% of the total combined voting power of all classes of stock of the corporation entitled to vote or at least 80% of the total value of the stock of the corporation.

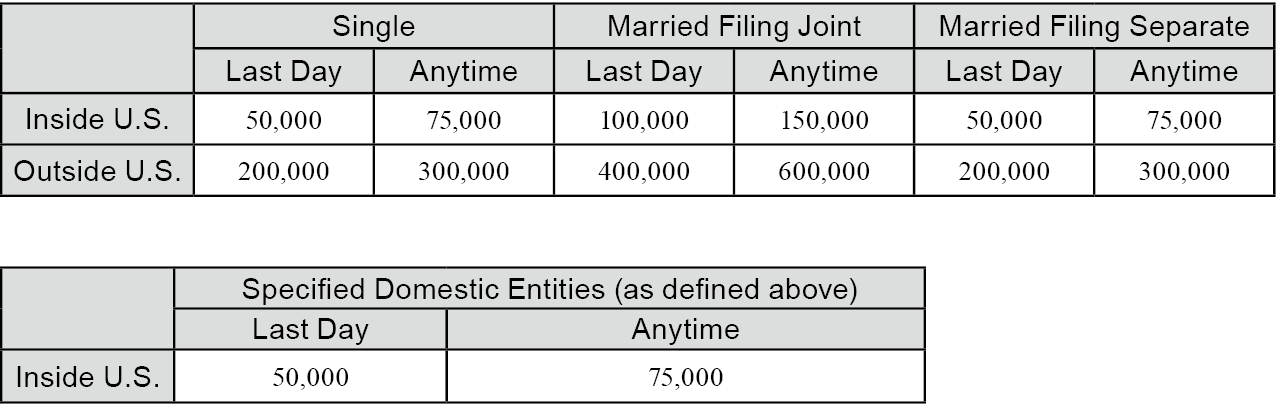

Applicable Reporting Threshold

If you are a specified individual, your applicable reporting threshold depends upon whether you are married, file a joint federal income tax return, and live inside (or outside) the United States.

You satisfy the reporting threshold only if:

(1) the total value of your specified foreign financial assets exceeds the amount specified under “Last Day” on the last day of the tax year; or

(2) the total value of your specified foreign financial assets exceeds the amount specified under “Anytime” at any time during the tax year.

What are the penalties for the failure to file Form 8938?

If you are required to file Form 8938 but do not file a complete and correct Form 8938 by the due date (including extensions), you may be subject to a penalty of $10,000. If you do not file a correct and complete Form 8938 within 90 days after the IRS mails you a notice of the failure to file, you may be subject to an additional penalty of $10,000 for each 30-day period (or part of a period) during which you continue to fail to file Form 8938 after the 90-day period has expired. The maximum additional penalty for a continuing failure to file Form 8938 is $50,000.

Reasonable Cause Exception

No penalty will be imposed if you fail to file Form 8938 or to disclose one or more specified foreign financial assets on Form 8938 and the failure is due to reasonable cause and not to willful neglect. You must affirmatively show the facts that support a reasonable cause claim. The determination of whether a failure to disclose a specified foreign financial asset on Form 8938 was due to reasonable cause and not due to willful neglect will be determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into account all pertinent facts and circumstances.

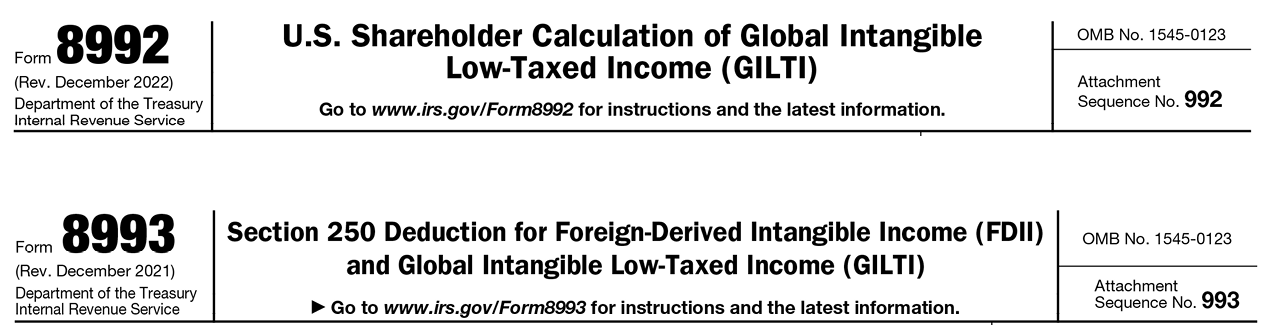

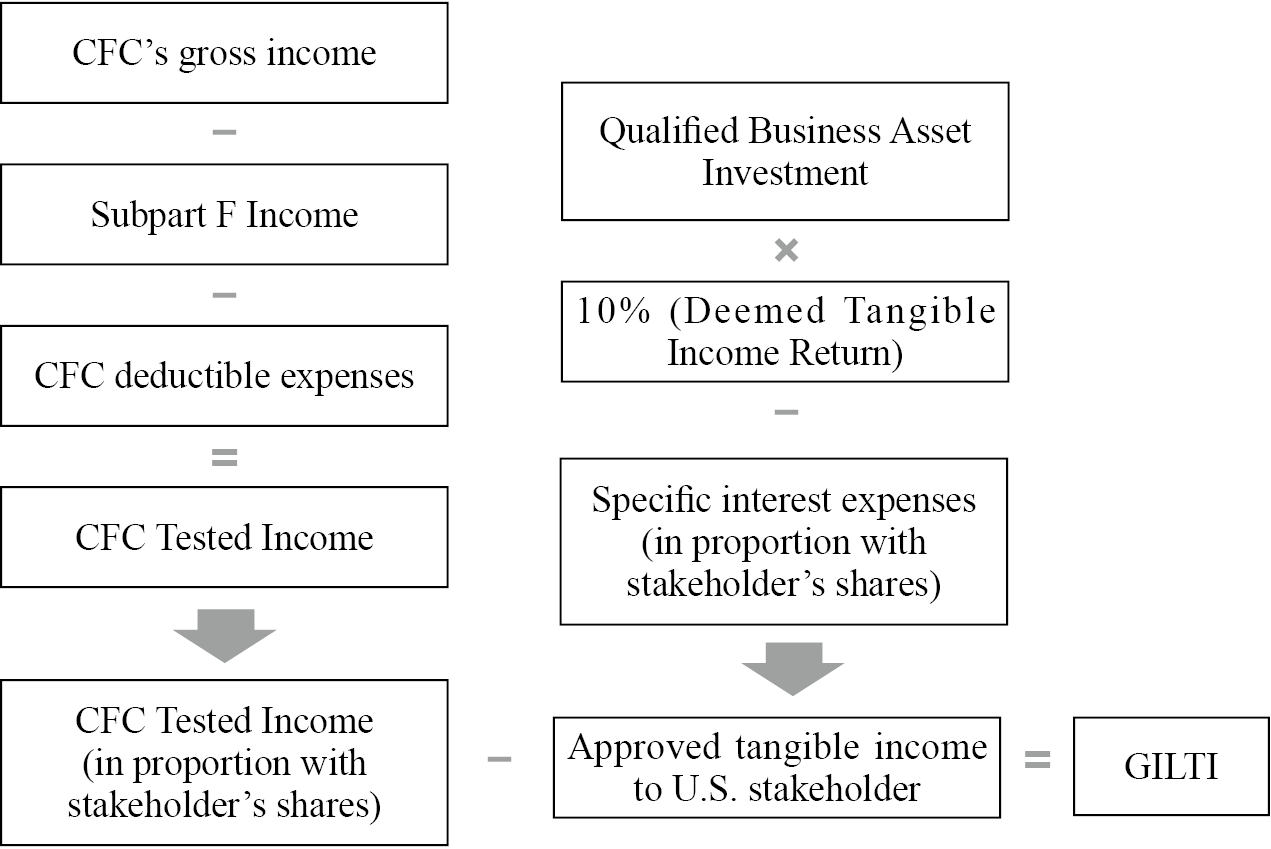

Generally, a person who is a U.S. shareholder of at least one foreign corporation (ownership of at least 10%) that is considered a CFC must file Form 8992.

All domestic corporations (and U.S. individual shareholders of controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) making a section 962 election (962 electing individual)) must use Form 8993 to determine the allowable deduction under section 250. A section 962 election, when properly elected, can:

- allow individual CFC shareholders the ability to offset their subpart F liability with foreign tax credits for taxes paid by the CFC.

- reduce the income tax consequence of a GILTI inclusion to only 10.5 percent.

- generate a second layer of tax as if the CFC shareholder received a dividend from a C corporation (which could potentially be beneficial for income tax purposes).

When an individual U.S. shareholder of a CFC has an income inclusion under either Subpart F or GILTI and makes an election pursuant to Sec. 962 to be taxed at corporate rates, the amount of income itself is not reported on Form 1040. Instead, taxpayers must track that information separately, attach a statement to the tax return, and report any tax directly on Form 1040, line 12a.

A 10% U.S. shareholder of a CFC is required to report inclusions of GILT and Subpart F income on the U.S. federal income tax return. A U.S. shareholder’s direct and indirect ownership percentages of a CFC under I.R.C. § 958(a) determine the allocable share of GILTI.

In the chart below, you can find a simplified version of the GILTI tax computations. It is generally advisable for you to seek professional advice regarding these calculations to ensure that the forms and eligible elections are properly filed.

Form SS-4 is used when applying for an Employer Identification Number (EIN). An EIN is a nine-digit number the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) assigns to employers, sole proprietors, corporations, partnerships, estates, trusts, and other entities for tax filing and reporting purposes. When starting a new U.S. business, you will generally need to apply for an EIN using Form SS-4.

Before you complete your Form SS-4, you should prepare by doing the following:

You can submit your Form SS-4 on the IRS’s online application, via fax or by mail. If you use the online application, you will receive your EIN immediately. Phone applications are only available for international applicants. If you have no legal residence, principal place of business, or principal office or agency in the U.S. or U.S. territories, you can’t use the online application to obtain an EIN. In certain cases, the online application for an EIN may be rejected, in which case, you may be required to call, mail, or fax the information to the IRS instead.

Before you complete your Form SS-4, you should prepare by doing the following:

- Determine the legal name of your business.

- Determine if the business has a trade name (i.e., doing business as, or DBA) that is different from its legal name.

- Know whether the business is a corporation, partnership or LLC.

- Determine the mailing address of your business.

- Gather information about the individual responsible for the business, including their tax ID number.

- Know the business start date and closing month of the accounting year.

You can submit your Form SS-4 on the IRS’s online application, via fax or by mail. If you use the online application, you will receive your EIN immediately. Phone applications are only available for international applicants. If you have no legal residence, principal place of business, or principal office or agency in the U.S. or U.S. territories, you can’t use the online application to obtain an EIN. In certain cases, the online application for an EIN may be rejected, in which case, you may be required to call, mail, or fax the information to the IRS instead.

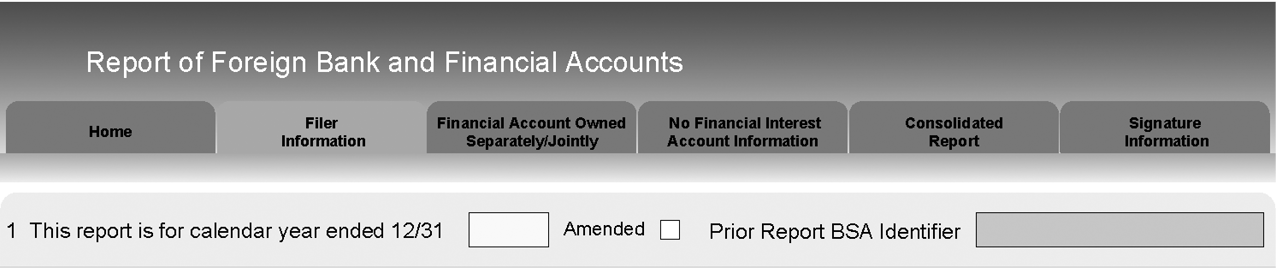

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) gives the Department of Treasury the authority to collect information from United States persons, including expats, who have financial interests in or signature authority over financial accounts maintained with financial institutions located outside of the United States.

The BSA requires that a Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) Report 114, Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR), be filed if the maximum values of the foreign financial accounts exceed $10,000 in the aggregate at any time during the calendar year.

Essentially, any U.S. person who owns a financial account outside of the U.S. generally must file FinCEN Form 114. These “accounts” include:

- Bank accounts (savings accounts, checking accounts and fixed deposit accounts)

- Securities accounts (stocks, bonds, and derivatives)

- Insurance (any policy that has a cash value)

- FBAR Civil Penalties:

-

- Negligent or “non-willful” delinquency can result in a penalty of $10,000 per account per year unless there is reasonable cause for failing to file.

- A “willful” failure to file could be subject to civil penalties equal to the greater of $100,000 or 50% of the balance in each unreported account.

- FBAR Criminal Penalties: A willful violation can result in fines of up to $250,000 and 5 years of jail time.

The FBAR is an annual report, due April 15 following the calendar year reported. You’re allowed an automatic extension to October 15 if you fail to meet the FBAR annual due date of April 15. You don’t need to request an extension to file the FBAR.

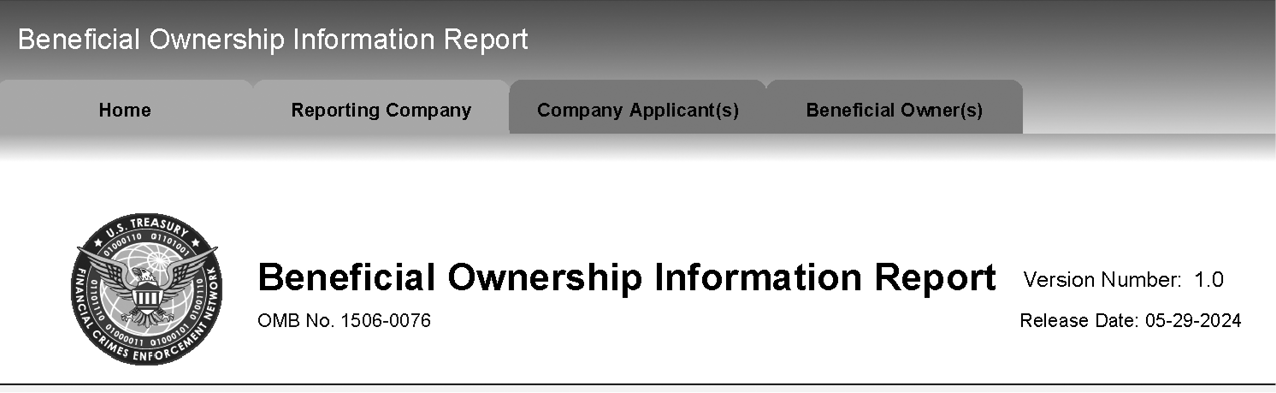

The Corporate Transparency Act (“CTA”) enacted by Congress requires that existing and newly formed or registered corporations, limited liability companies, and other business entities operating in the United States report beneficial ownership information in the form of a Beneficial Ownership Information Report (“BOIR”).

(1) The Corporate Transparency Act and FinCEN

The Corporate Transparency Act aims to combat illicit financial activities by requiring entities subject to its regulations to submit BOIR to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) of the U.S. Department of the Treasury within specified deadlines (detailed below).

(2) Requirements for Beneficial Ownership Information Reports (BOIR)

Entities subject to the regulations (“Reporting Companies”) must submit their initial reports by the following deadlines:

The BOIR is not an annual requirement. A reporting company is required to file a BOIR upon formation within a certain allotted timeframe and after there is a change in the company’s beneficial ownership. Generally, reporting companies must provide the following information:

- Name of each beneficial owner (“BO”), as defined by FinCEN.

- Date of birth of each BO.

- Address of each BO.

- Personal identification of each BO (valid passport, driver’s license, or ID).

- Information about the Reporting Company itself, including its name and address.

- Companies established on or after January 1, 2024, must also submit information about the individuals establishing the company (“Company Applicant”).

Potential violations include intentionally failing to submit BOIR, intentionally submitting incorrect BOIR, or intentionally failing to correct or update previously submitted BOIR. Violators may face civil penalties of up to $592 per day for the duration of the violation and criminal penalties of up to $10,000 and up to two years of imprisonment.

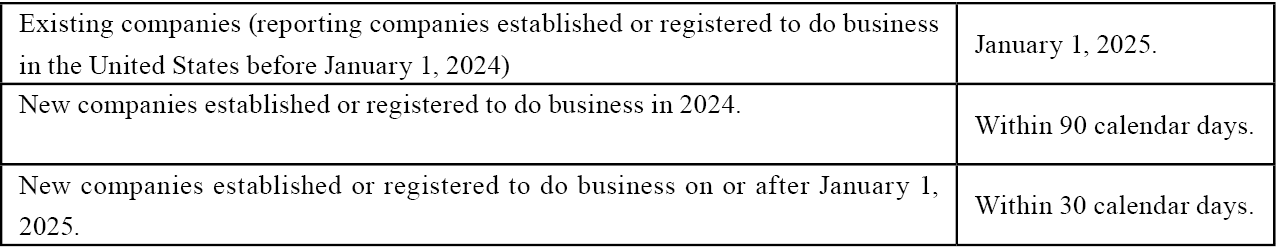

Effective July 1, 2014, the IRS began to offer two types of Streamlined Procedures, herein referred to as “Streamline”:

(1) Streamlined Foreign Offshore Procedures (“SFOP”)

-For U.S. taxpayers residing outside the United States

(2) Streamlined Domestic Offshore Procedures (“SDOP”)

-For U.S. taxpayers residing within the United States

Taxpayers who are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents (e.g., Green Card Holders) are considered to reside outside the United States if:

For at least one of the three Streamline years, the individual:

(1) did not have a U.S. “abode” (generally, one’s home, habitation, residence, domicile, or place of dwelling); and

(2) was physically outside the United States for at least 330 full days (meaning, the taxpayer did not spend more than 35 days in the United States).

Under Streamline, the taxpayer is generally required to submit:

- 3 years of tax returns and information returns

- 6 years of Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (“FBARs”) on Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) Form 114

- Non-willful certification (U.S. Resident: Form 14654, Non-US: Form 14653)

Domestic Streamline differs from Foreign Streamline in two main ways:

(1) A domestic resident taxpayer that has failed to file a U.S. income tax return in any of the three most recent tax years cannot participate in Domestic Streamline (while a foreign resident taxpayer that has been similarly delinquent can participate in the Foreign Streamline).

(2) Further, even if the taxpayer qualifies, Domestic Streamline bear a 5% miscellaneous penalty on the highest aggregate balance/value of one’s foreign financial assets (i.e., assets reportable on the FBAR or Form 8938) during the FBAR period. Foreign Streamline does not have this penalty.

Non-Willful Standard

The language of the certification forms seems to offer a broader range of conduct that will be considered non-willful for purposes of Streamline.

In the form, the taxpayer must certify the following:

“My failure to report all income, pay all tax, and submit all required information returns, including FBARs, was due to non-willful conduct. I understand that non-willful conduct is conduct that is due to negligence, inadvertence, or mistake or conduct that is the result of a good faith misunderstanding of the requirements of the law.”

The IRS does not send successful applicants an acceptance or closing letter. In this sense, “no news is good news.” If the IRS does not receive adequate information in the Streamline submission, it will often follow up with the taxpayer and ask for that information.

It may ask for:

- More detailed account information

- More detailed foreign entity information

- More information about the professional whose advice you relied upon

- A further explanation to support your claim of non-willful conduct

If the IRS receives or discovers evidence of willfulness or criminal conduct on the part of the taxpayer (e.g., information received from foreign governments or financial institutions), the IRS could open an examination or investigation that could lead to civil fraud penalties, FBAR penalties, information return penalties, or even a referral to Criminal Investigation. Entrance to the Streamlined program does not guarantee immunity from criminal prosecution.

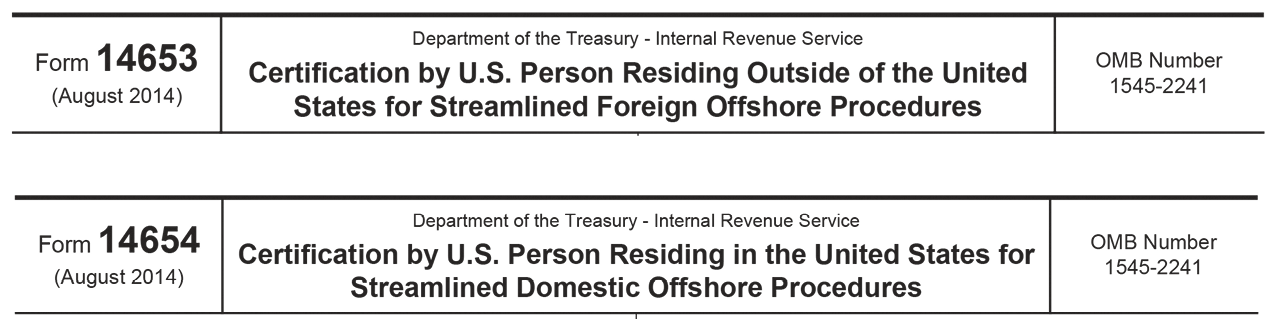

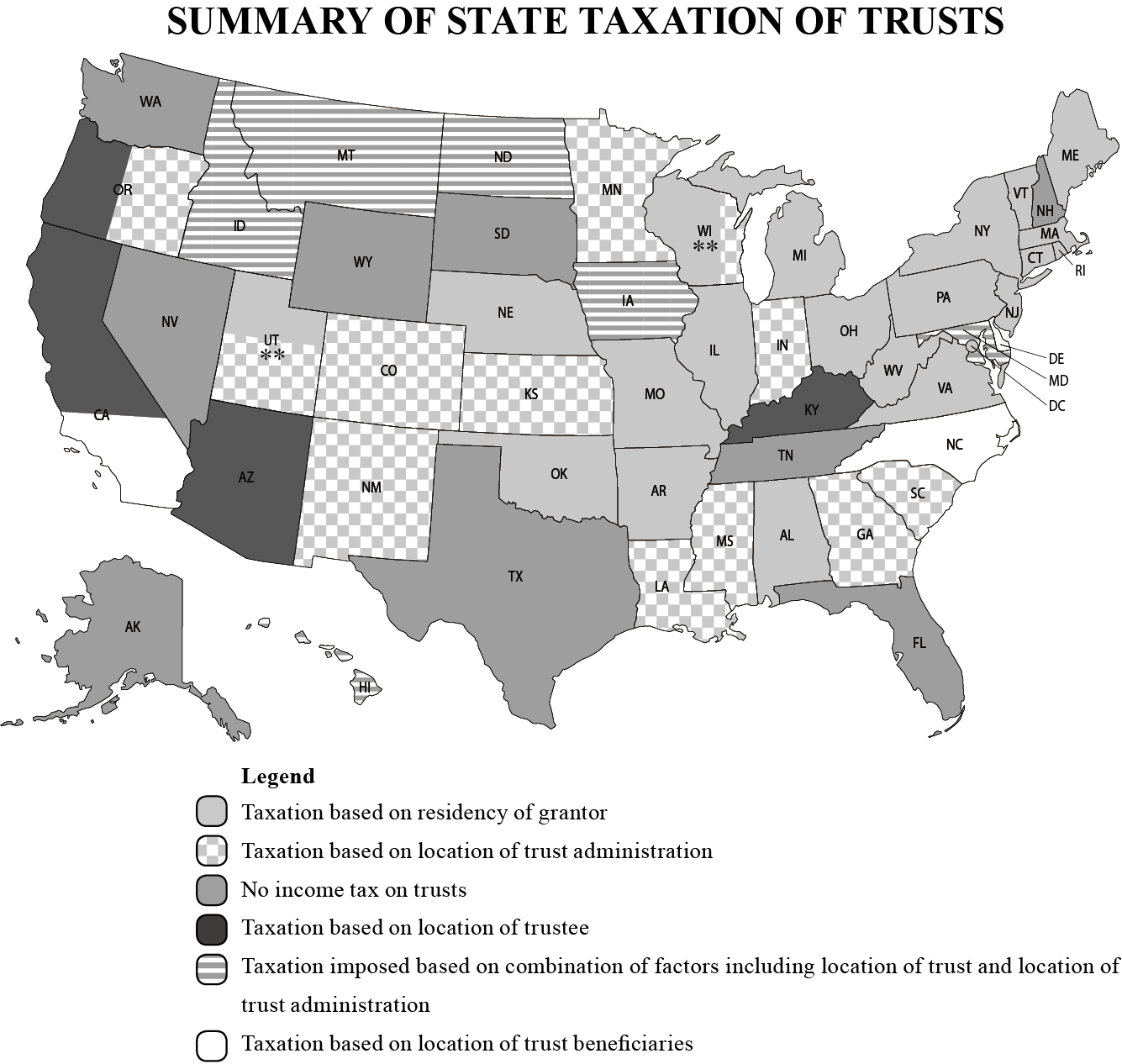

When it comes to taxes, oftentimes clients focus almost exclusively on completing their federal tax obligations; however, state law and state taxation should play a part in the clients’ trust and estate planning as well. In addition to taxing trusts that are administered in California, the Franchise Tax Board of California (FTB) also imposes taxes on trusts that have fiduciaries and beneficiaries based in California. Below you can find a map of the U.S., with how various states impose income taxes on trusts.

If an irrevocable non-grantor trust has one the following characteristics, it will be deemed a California trust (for California income tax purposes):

(1) One or more California trustee(s)

(2) One or more California fiduciaries (including the Trust Protector, Trust Distribution Advisor or Trust Investment Direction Advisor)

(3) One or more California beneficiaries receiving a distribution in that tax year

A California trust is required to file an income tax return in California if the trust: (i) has net income from all sources in excess of $100; or (ii) has gross income from all sources in excess of $10,000, regardless of the amount of net income. Taxes due in connection with a Form 541 along with the form are due on April 15; however, taxpayers are generally allotted a filing extension (without filing an extension) until October 15.

While state taxes often come as an afterthought when it comes to estate planning, Wealth Creators should be mindful when it comes to the jurisdiction(s) of the trusts’ fiduciaries when settling a trust. In addition, special attention should be paid to those with California residency. This is especially the case when a trust makes distributions of income to California tax residents, as doing so may trigger both high California state income taxes and California “throwback” taxes.