Publications

U.S. Trust and Estate Planning 美國信託規劃實務(英文部分)

Chapter 2 U.S. Irrevocable Dynasty Trusts

A Dynasty Trust is a trust settled with the primary purpose of transitioning wealth from one generation to one or more future generations. An irrevocable Dynasty Trust simply implies that gifts made by the Grantor to the trust are not distributable back to the Grantor at the Grantor’s discretion, but rather controlled by fiduciaries appointed by the Grantor to protect and manage for the benefit of the trust’s beneficiaries, often the Grantor’s U.S.-based descendants or relatives.

A Dynasty Trust is a trust settled with the primary purpose of transitioning wealth from one generation to one or more future generations. An irrevocable Dynasty Trust simply implies that gifts made by the Grantor to the trust are not distributable back to the Grantor at the Grantor’s discretion, but rather controlled by fiduciaries appointed by the Grantor to protect and manage for the benefit of the trust’s beneficiaries, often the Grantor’s U.S.-based descendants or relatives.

Few vehicles can compare to a U.S. Dynasty Trust when it comes to passing down familial wealth from one generation to future generations. This is especially true in countries with a transfer tax (a tax on wealth transfers between individuals). Transferring wealth in the U.S. is especially pricey, generally costing 40% or more of the wealth being transferred either through a gift tax or through an estate tax. As such, Wealth Creators based in the U.S. often must consider ways to maximize their lifetime gift and estate tax exemption ($13.61 million for individuals and double for married couples in 2024).

Fortunately for first generation non-U.S. Wealth Creators, the U.S. tax code has built in certain exceptions from U.S. transfer taxes. In addition, they may also be exempt from U.S. income tax if income derived is sourced from non-U.S. sources. When properly structured, a Dynasty Trust should serve the purposes of transferring wealth and minimizing transfer taxes.

Few vehicles can compare to a U.S. Dynasty Trust when it comes to passing down familial wealth from one generation to future generations. This is especially true in countries with a transfer tax (a tax on wealth transfers between individuals). Transferring wealth in the U.S. is especially pricey, generally costing 40% or more of the wealth being transferred either through a gift tax or through an estate tax. As such, Wealth Creators based in the U.S. often must consider ways to maximize their lifetime gift and estate tax exemption ($13.61 million for individuals and double for married couples in 2024).

Fortunately for first generation non-U.S. Wealth Creators, the U.S. tax code has built in certain exceptions from U.S. transfer taxes. In addition, they may also be exempt from U.S. income tax if income derived is sourced from non-U.S. sources. When properly structured, a Dynasty Trust should serve the purposes of transferring wealth and minimizing transfer taxes.

The U.S. Irrevocable Trust is one such vehicle that, when properly structured, has the ability to shelter assets from U.S. transfer taxes almost indefinitely. It does so by having the Grantor transfer assets to the trust irrevocably, thereby completing a gift. After the gift is completed, the Grantor is no longer the legal owner of the assets transferred.

Non-U.S. Wealth Creators should consider seeking counsel when making gifts, especially as it relates to completed gifts because they are irrevocable by definition and can quite easily trigger a gift tax (40%+ of the value of the gift) when the gift consists of U.S.-situs assets. In contrast, gifting non-U.S. situs assets into a U.S. Irrevocable Trust generally does not incur any gift tax. Furthermore, even if these non-U.S. situs assets are liquidated and reinvested in U.S. situs assets, the Grantor’s death should not trigger any U.S. estate tax for assets previously gifted.

Each U.S. state has different regulations regarding the governance of trusts, with certain states being more favorable trust jurisdictions than others. In certain states, rules against perpetuities are in place, defining a definite lifespan for trusts; in other states, trust income may be taxed at high rates. Many Asian Wealth Creators choose to establish their trusts in Nevada or Delaware.

This chapter explores the U.S. irrevocable trust in detail; specifically, it addresses the purpose(s) of establishing a U.S. irrevocable trust, the tax ramifications of a U.S. irrevocable trust and how control of the U.S. irrevocable trust is distributed.

In summary, U.S. irrevocable trusts, when structured as directed trusts, often allow non-U.S. persons to make gifts to U.S. descendants while (1) allowing for the assets to be controlled and protected by trusted persons assigned as fiduciaries and (2) protecting future generations from U.S. transfer taxes. Wealth Creators who seek to permanently transfer assets into the U.S. for the benefit of U.S. beneficiaries should evaluate the merits of such a trust.

Non-U.S. Wealth Creators should consider seeking counsel when making gifts, especially as it relates to completed gifts because they are irrevocable by definition and can quite easily trigger a gift tax (40%+ of the value of the gift) when the gift consists of U.S.-situs assets. In contrast, gifting non-U.S. situs assets into a U.S. Irrevocable Trust generally does not incur any gift tax. Furthermore, even if these non-U.S. situs assets are liquidated and reinvested in U.S. situs assets, the Grantor’s death should not trigger any U.S. estate tax for assets previously gifted.

Each U.S. state has different regulations regarding the governance of trusts, with certain states being more favorable trust jurisdictions than others. In certain states, rules against perpetuities are in place, defining a definite lifespan for trusts; in other states, trust income may be taxed at high rates. Many Asian Wealth Creators choose to establish their trusts in Nevada or Delaware.

This chapter explores the U.S. irrevocable trust in detail; specifically, it addresses the purpose(s) of establishing a U.S. irrevocable trust, the tax ramifications of a U.S. irrevocable trust and how control of the U.S. irrevocable trust is distributed.

In summary, U.S. irrevocable trusts, when structured as directed trusts, often allow non-U.S. persons to make gifts to U.S. descendants while (1) allowing for the assets to be controlled and protected by trusted persons assigned as fiduciaries and (2) protecting future generations from U.S. transfer taxes. Wealth Creators who seek to permanently transfer assets into the U.S. for the benefit of U.S. beneficiaries should evaluate the merits of such a trust.

Many irrevocable Dynasty Trusts are structured as directed trusts, especially those settled by Asian Wealth Creators. In the U.S., the Trustees have historically held many of the key management powers within Dynasty Trusts, including the power to allocate the trust’s investments and the power to determine the trust’s distributions. Over time, however, many Wealth Creators realized that they would rather have trusted and named fiduciaries make those decisions, rather than Trustees that may or may not have similar values aligned with their beliefs. Furthermore, when Trustees must make investment or distribution decisions on behalf of trusts, the potential legal liabilities of Trustees are noticeably increased, which leads to higher maintenance fees usually pegged as a percentage of total assets under administration.

While Wealth Creators who set up trusts in the U.S. typically seek to transfer their assets to their descendants or family members, trusts in Asia are often settled with the sole intent of directing assets towards investments. Many Asia-based financial advisors at large financial institutions sell trusts as a way to market their investment products. In the vast majority of these trusts, the trustee holds a tremendous amount of power over the trust and the trust agreement is almost always drafted to benefit the trustee or its affiliate, which frequently earns revenue as a percentage of assets held. Furthermore, financial advisors typically have little to no room for modifications in the trust agreement’s templated language, reducing the clients’ ability to tailor the contract to their needs.

In contrast to their Asian counterparts, U.S. trusts are typically drafted by qualified attorneys for the sole benefit of the clients themselves. While this process requires a separate legal fee (billed either as a flat fee or an hourly fee), as attorneys do not earn revenue based on assets managed like an investment manager does, the trust agreement is tailored to the client’s specific needs. This usually means that the Wealth Creators have more say as to who will hold the powers to invest and distribute the trust’s assets.

As such, U.S. trusts may suit the needs of these Wealth Creators more. In U.S. directed trusts, the Grantor gets to appoint fiduciaries that can control substantially all operations of the trust, often leaving trustees with purely administrative functions such as keeping track of the trust’s paperwork and signing off on the trust’s tax forms. As the trustee’s control over the trust is minimized, the trustee’s liability is also minimized, leading to lower fees (often a flat annual fee, rather than a fee based on a percentage of assets).

Relevant Considerations

A trust is generally established for the benefit of its Beneficiaries. The trust’s Grantor appoints a Trustee to manage the administration of trust assets. Typically, at the time the trust is formed, the Grantor appoints relevant fiduciaries and assigns various powers to each fiduciary.

This structure allows the Grantor’s descendants and / or other named Beneficiaries to benefit from trust distributions (as determined by the Distribution Advisor), without the trust assets being directly includible in the Beneficiaries’ personal assets. When structured properly, creditors of trust Beneficiaries are not able to enforce their claims against the assets held in a trust.

A Dynasty Trust may be structured as a Grantor Trust or Non-Grantor Trust for U.S. income tax purposes. A trust is generally considered a “Grantor Trust” if the Grantor is liable for paying income taxes on the trust’s income. A trust is considered a “Non-Grantor trust" if the trust’s Grantor is not liable for income taxes attributable to the trust’s income.

Under the U.S. Federal Income Tax regime, a U.S. trust is generally treated as a U.S. income tax resident. The IRC clearly defines a U.S. trusts for U.S. income tax purposes under IRC §§ 7701(a)(30)(E) and (31)(B), effected in 1996. A trust is a U.S. trust when both of the following conditions are satisfied. A trust is considered a foreign trust if either of the two following conditions are not satisfied.

Thus, by definition, a U.S. trust is a trust governed by U.S. courts and has a U.S. person controller. Furthermore, a foreign trust, by definition, is a trust that does not fulfill either the Court Test or the Control Test and thus, cannot be considered a U.S. trust. To establish a U.S. trust, the Court and Control Tests are often satisfied by trust agreements that:

When these conditions are met, a trust is considered to be a U.S. trust and governed by both U.S. Federal laws and State laws (usually in the state the trust is established). For U.S. taxpayers, a U.S. trust is frequently preferable to a Foreign Trust, especially as it relates to income tax purposes (with a limited exceptions for certain Foreign Trusts settled by non-U.S. persons). In trust agreements where the Trust Protector holds substantially all relevant powers, the Trust Protector must be a U.S. person (or U.S. corporation) for the trust to be a U.S. trust.

In accordance with Treasury Reg. 301-7701-7(d)(2), if a U.S. Trustee is replaced by a foreign Trustee, the trust is allotted 12 months to replace the Foreign Trustee with a U.S. Trustee to maintain U.S. trust status. If the change is not made within the 12 months specified, the trust will be treated as a Foreign Trust from the date the Trustee changes.

While Wealth Creators who set up trusts in the U.S. typically seek to transfer their assets to their descendants or family members, trusts in Asia are often settled with the sole intent of directing assets towards investments. Many Asia-based financial advisors at large financial institutions sell trusts as a way to market their investment products. In the vast majority of these trusts, the trustee holds a tremendous amount of power over the trust and the trust agreement is almost always drafted to benefit the trustee or its affiliate, which frequently earns revenue as a percentage of assets held. Furthermore, financial advisors typically have little to no room for modifications in the trust agreement’s templated language, reducing the clients’ ability to tailor the contract to their needs.

In contrast to their Asian counterparts, U.S. trusts are typically drafted by qualified attorneys for the sole benefit of the clients themselves. While this process requires a separate legal fee (billed either as a flat fee or an hourly fee), as attorneys do not earn revenue based on assets managed like an investment manager does, the trust agreement is tailored to the client’s specific needs. This usually means that the Wealth Creators have more say as to who will hold the powers to invest and distribute the trust’s assets.

As such, U.S. trusts may suit the needs of these Wealth Creators more. In U.S. directed trusts, the Grantor gets to appoint fiduciaries that can control substantially all operations of the trust, often leaving trustees with purely administrative functions such as keeping track of the trust’s paperwork and signing off on the trust’s tax forms. As the trustee’s control over the trust is minimized, the trustee’s liability is also minimized, leading to lower fees (often a flat annual fee, rather than a fee based on a percentage of assets).

Relevant Considerations

A trust is generally established for the benefit of its Beneficiaries. The trust’s Grantor appoints a Trustee to manage the administration of trust assets. Typically, at the time the trust is formed, the Grantor appoints relevant fiduciaries and assigns various powers to each fiduciary.

This structure allows the Grantor’s descendants and / or other named Beneficiaries to benefit from trust distributions (as determined by the Distribution Advisor), without the trust assets being directly includible in the Beneficiaries’ personal assets. When structured properly, creditors of trust Beneficiaries are not able to enforce their claims against the assets held in a trust.

A Dynasty Trust may be structured as a Grantor Trust or Non-Grantor Trust for U.S. income tax purposes. A trust is generally considered a “Grantor Trust” if the Grantor is liable for paying income taxes on the trust’s income. A trust is considered a “Non-Grantor trust" if the trust’s Grantor is not liable for income taxes attributable to the trust’s income.

Under the U.S. Federal Income Tax regime, a U.S. trust is generally treated as a U.S. income tax resident. The IRC clearly defines a U.S. trusts for U.S. income tax purposes under IRC §§ 7701(a)(30)(E) and (31)(B), effected in 1996. A trust is a U.S. trust when both of the following conditions are satisfied. A trust is considered a foreign trust if either of the two following conditions are not satisfied.

1. A court within the U.S. is able to exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust (commonly referred to as the “Court Test”) AND

2. One or more U.S. persons have the authority to control all substantial decisions of the trust (commonly referred to as the “Control Test”).

Thus, by definition, a U.S. trust is a trust governed by U.S. courts and has a U.S. person controller. Furthermore, a foreign trust, by definition, is a trust that does not fulfill either the Court Test or the Control Test and thus, cannot be considered a U.S. trust. To establish a U.S. trust, the Court and Control Tests are often satisfied by trust agreements that:

1. state explicitly that a U.S. court has jurisdiction;

2. have one or more U.S.-based Trustee, whom together, have substantial control over the administration of the trust; and

3. have one or more U.S. persons or U.S.-based corporations (generally U.S. LLCs or C-Corporations) control all substantial decisions.

When these conditions are met, a trust is considered to be a U.S. trust and governed by both U.S. Federal laws and State laws (usually in the state the trust is established). For U.S. taxpayers, a U.S. trust is frequently preferable to a Foreign Trust, especially as it relates to income tax purposes (with a limited exceptions for certain Foreign Trusts settled by non-U.S. persons). In trust agreements where the Trust Protector holds substantially all relevant powers, the Trust Protector must be a U.S. person (or U.S. corporation) for the trust to be a U.S. trust.

In accordance with Treasury Reg. 301-7701-7(d)(2), if a U.S. Trustee is replaced by a foreign Trustee, the trust is allotted 12 months to replace the Foreign Trustee with a U.S. Trustee to maintain U.S. trust status. If the change is not made within the 12 months specified, the trust will be treated as a Foreign Trust from the date the Trustee changes.

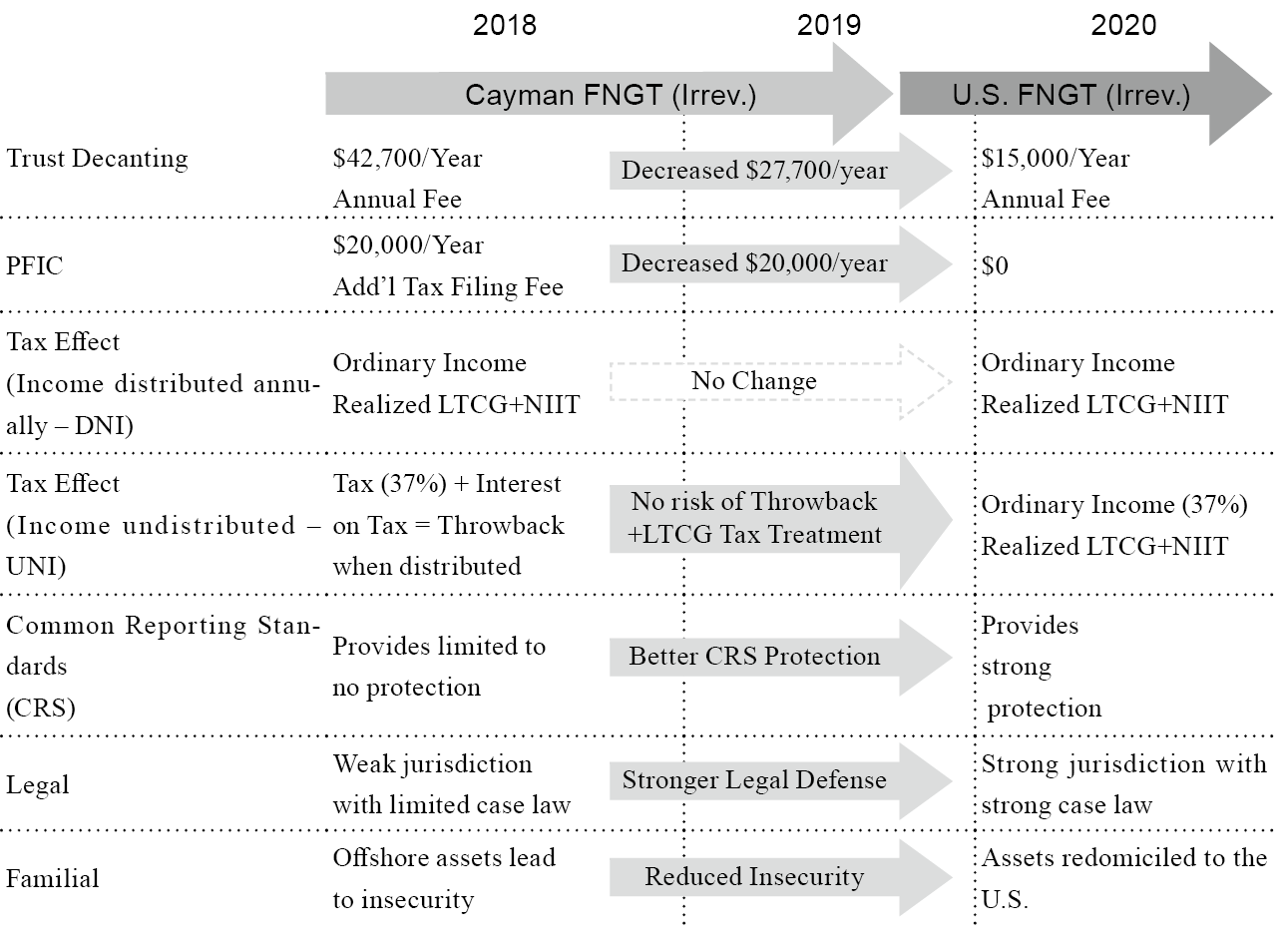

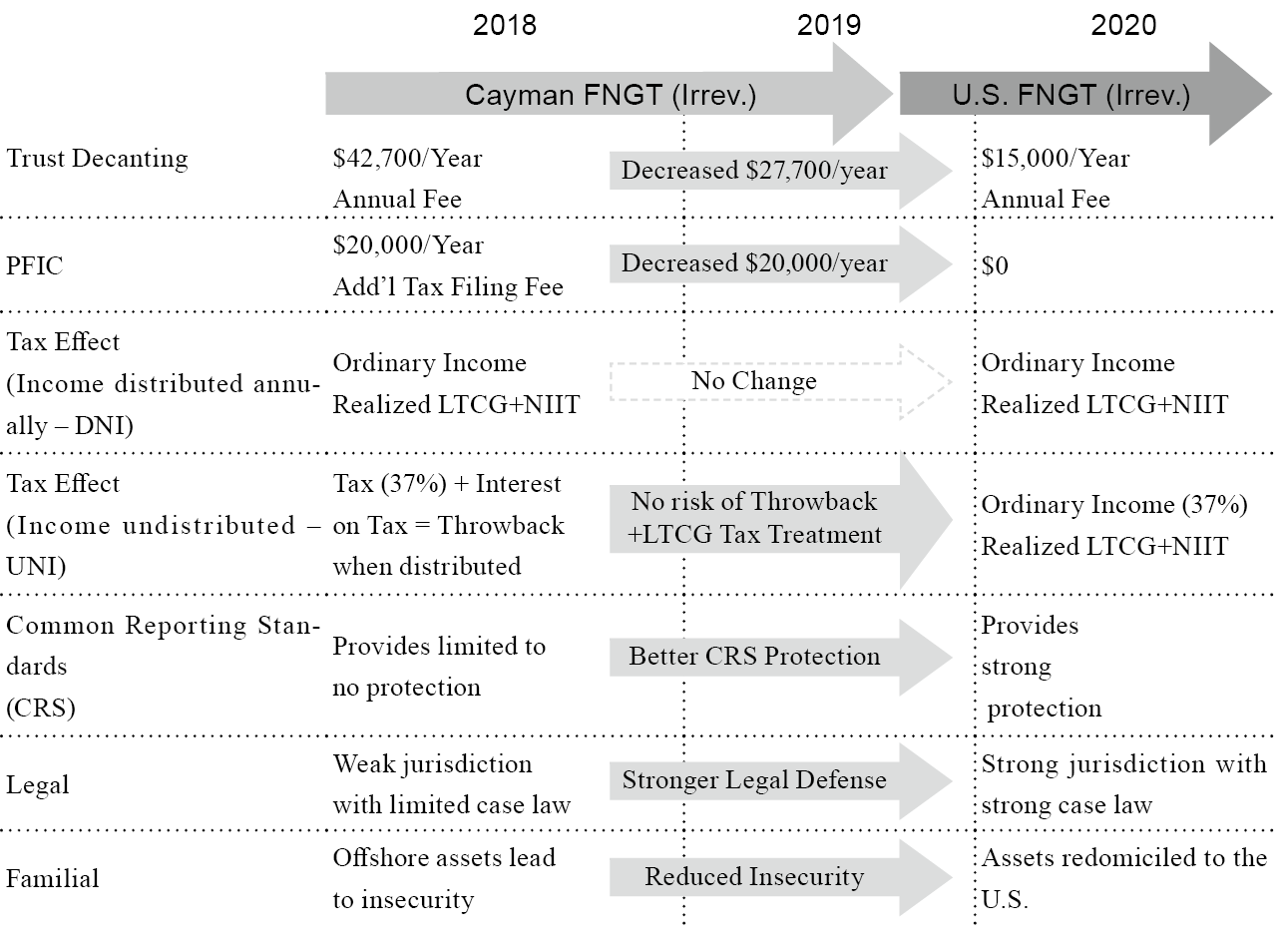

In prior decades, numerous Wealth Creators, often persuaded by their private bankers and financial advisors, have settled irrevocable trusts outside of the U.S. These trusts are frequently settled in less established jurisdictions (the Cayman Islands, BVI, Bermuda or Cook Islands, among others) and may have ambiguous legal situs. While often marketed as tools to help safeguard and invest assets for the next generation, these trusts often failed to accomplish its preset goals.

Over the years, descendants of these Wealth Creators have immigrated to the U.S., either receiving a U.S. citizenship or green card; however, this information is rarely if ever considered when crafting the family’s estate plan. Unbeknownst to many of these Wealth Creators, trusts established outside of the U.S. often do not serve the needs of their U.S.-based descendants and could potentially have calamitous tax consequences for their U.S. beneficiaries.

By decanting assets from an offshore irrevocable trust (one established outside of the U.S.) to a U.S.-based one, the Wealth Creator’s family can protect the trust’s assets more thoroughly and reduce its annual trust maintenance expenditures.

*LTCG refers to long-term capital gains, generally taxed at 20% for trusts

*NIIT refers to net investment income tax, generally taxed at 3.8% for trusts

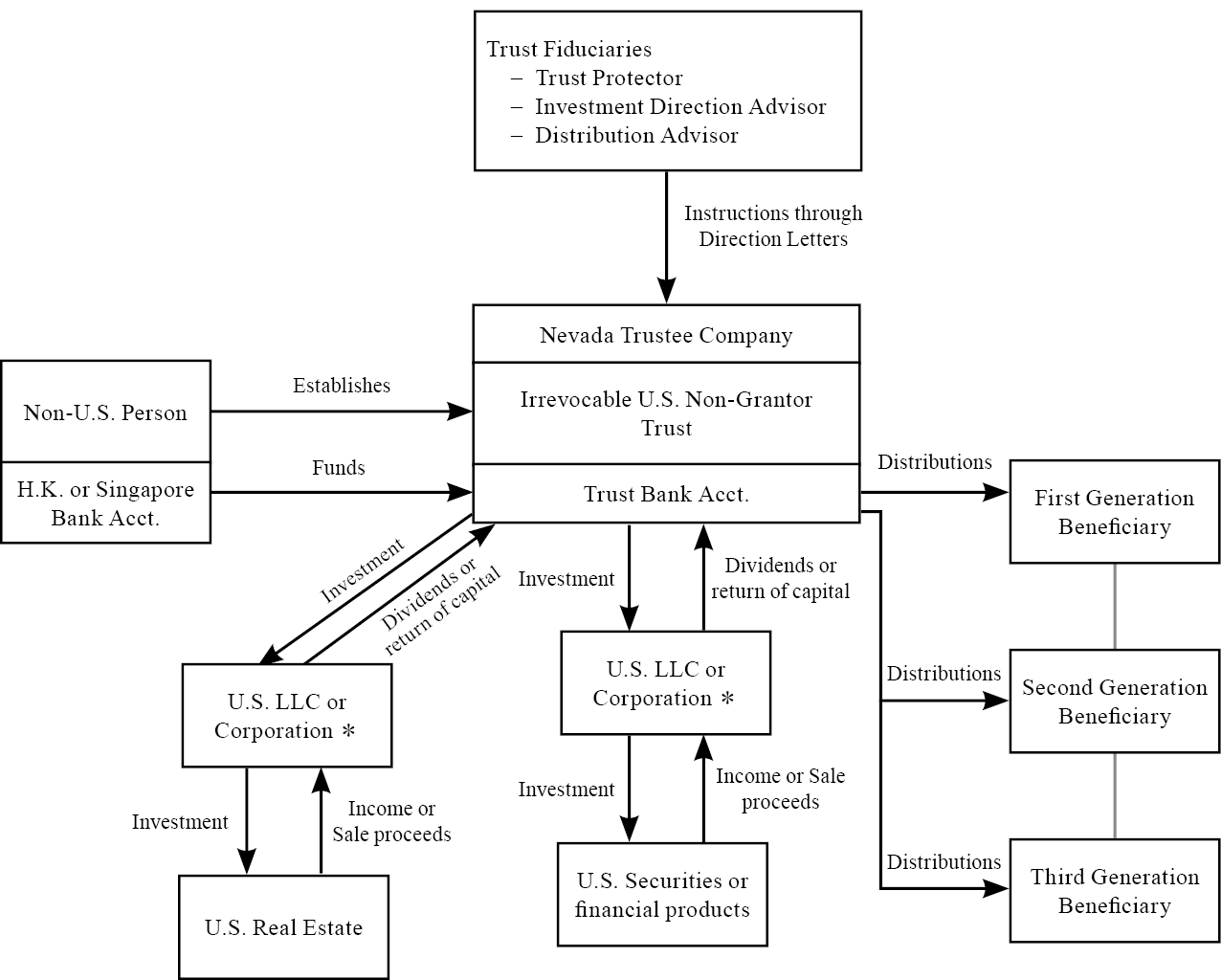

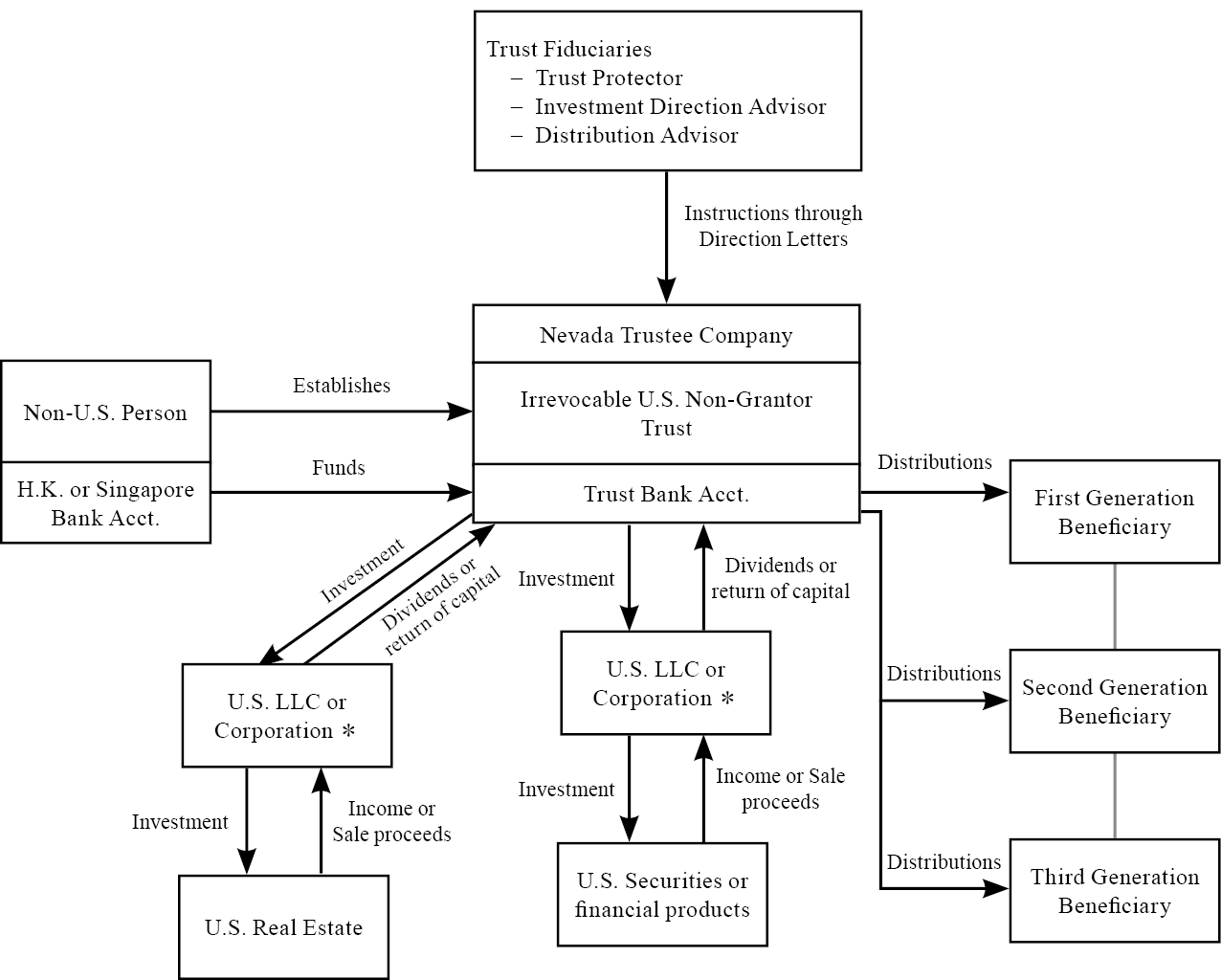

Illustrative Nevada Irrevocable Trust

*Managers or Directors of LLCs and Corporations may be the fiduciaries or beneficiaries of the irrevocable trust.

The above trust is settled by a non-U.S. person in Nevada. A Nevada Trust Company is selected as Trustee. The trust’s beneficiaries, designated by the grantor, are all U.S. persons. The trust invests in multiple wholly-owned LLCs and / or C-Corporations. These companies are invested in U.S. securities, time deposits and real estate.

Over the years, descendants of these Wealth Creators have immigrated to the U.S., either receiving a U.S. citizenship or green card; however, this information is rarely if ever considered when crafting the family’s estate plan. Unbeknownst to many of these Wealth Creators, trusts established outside of the U.S. often do not serve the needs of their U.S.-based descendants and could potentially have calamitous tax consequences for their U.S. beneficiaries.

By decanting assets from an offshore irrevocable trust (one established outside of the U.S.) to a U.S.-based one, the Wealth Creator’s family can protect the trust’s assets more thoroughly and reduce its annual trust maintenance expenditures.

*LTCG refers to long-term capital gains, generally taxed at 20% for trusts

*NIIT refers to net investment income tax, generally taxed at 3.8% for trusts

Illustrative Nevada Irrevocable Trust

*Managers or Directors of LLCs and Corporations may be the fiduciaries or beneficiaries of the irrevocable trust.

The above trust is settled by a non-U.S. person in Nevada. A Nevada Trust Company is selected as Trustee. The trust’s beneficiaries, designated by the grantor, are all U.S. persons. The trust invests in multiple wholly-owned LLCs and / or C-Corporations. These companies are invested in U.S. securities, time deposits and real estate.

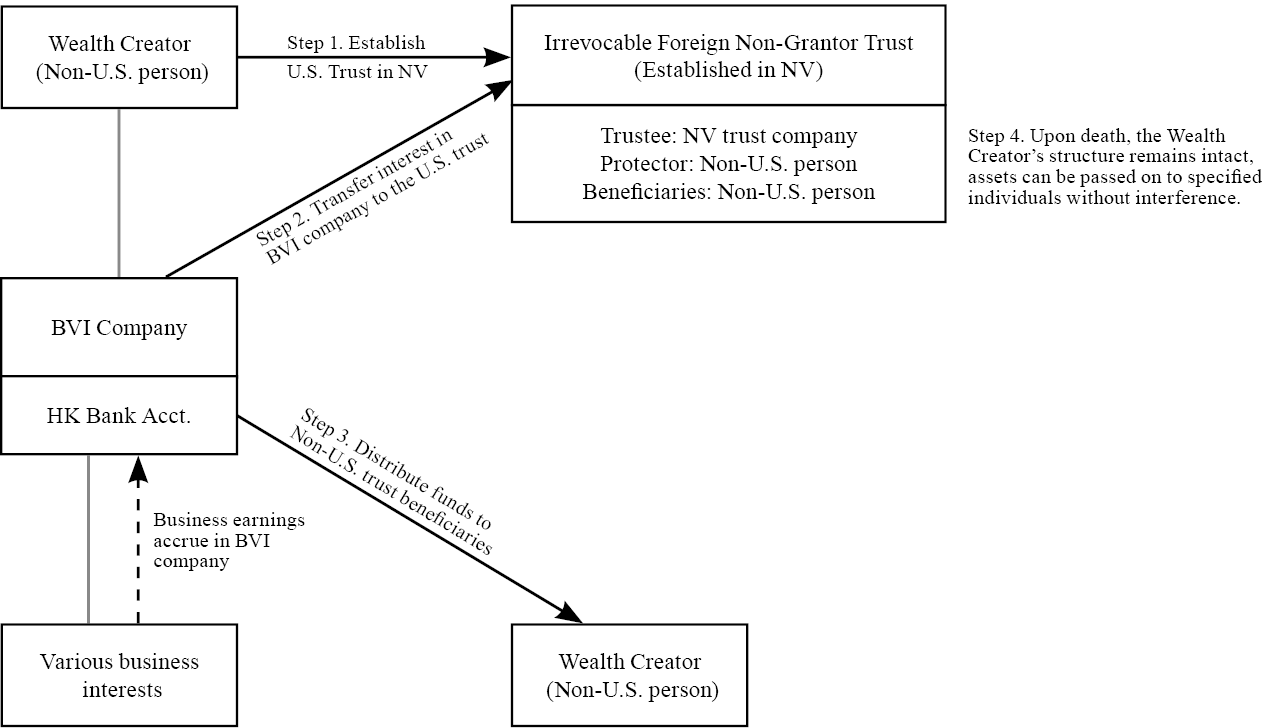

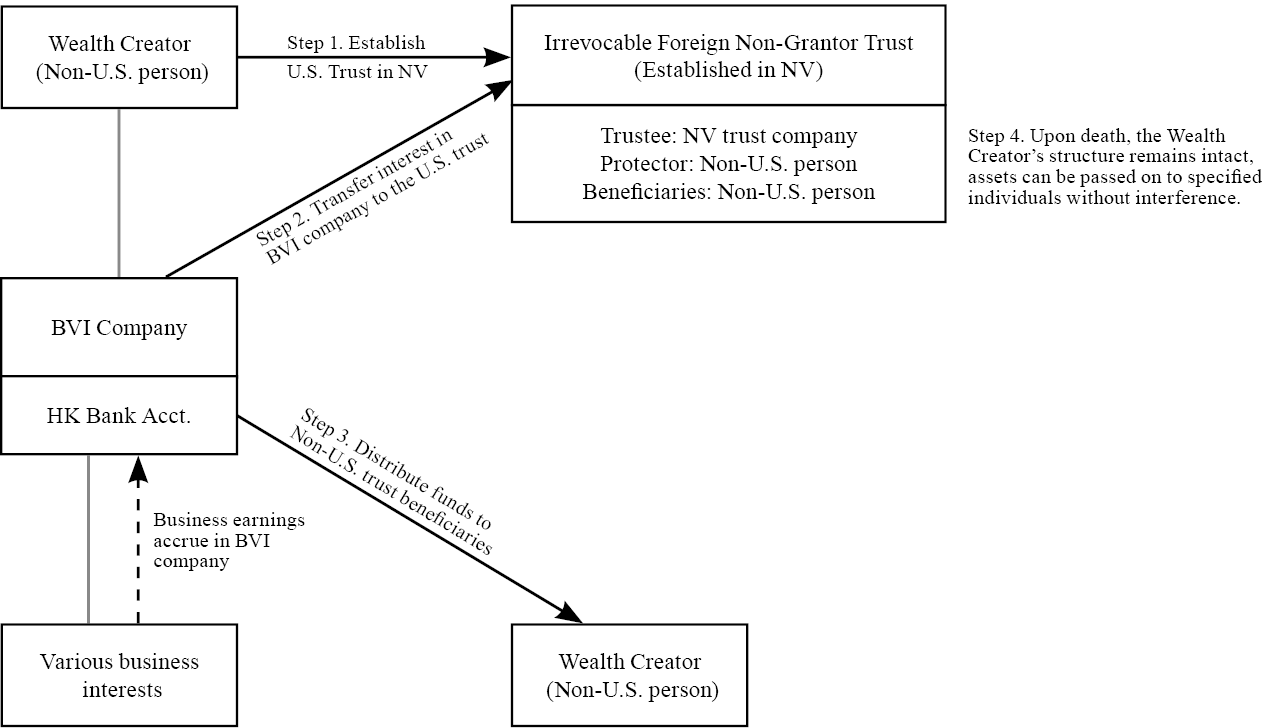

Wealth Creators with no U.S.-based descendants should consider establishing a Foreign Non-Grantor Trust in the U.S (see structure below).

By using this structure, the Wealth Creator attains several key benefits, without incurring additional expenses.

1 – Establishing a Nevada Irrevocable Trust (General Procedures)

While there are numerous benefits to settling an Irrevocable Trust, Wealth Creators, especially non-U.S. ones, often face considerable difficulty when selecting a firm to work with. When non-U.S. Wealth Creators set out to create a trust, they usually must contact the following service providers:

Each of these service providers will typically conduct their own due diligence on the clients’ needs, source of funds and any conflicts with existing clients (for the law firms). As a result, many non-U.S. Wealth Creators may find the process quite daunting. This is especially true when the wealth transfer process takes a number of years or when clients have drastic changes in their life circumstances.

The complexities of the structures necessary for non-U.S. persons to optimize their estate planning may also frequently result in miscommunication, delays in the setup process, difficulties in maintaining various holding structures and even the creation of inoperable structures, if the different service providers are communicating directly with the client only and not with each other.

The authors of this book are all managers of a global accounting and law firm headquartered in Taiwan. Over the past decade, we have worked with numerous U.S. and non-U.S. Wealth Creators on creating their succession plans, establishing over 150 trusts. As an integrated firm with offices in the U.S. and licensed professionals across Asia, we provide clients with services encompassing essential functions necessary for planning cross-border wealth transfer.

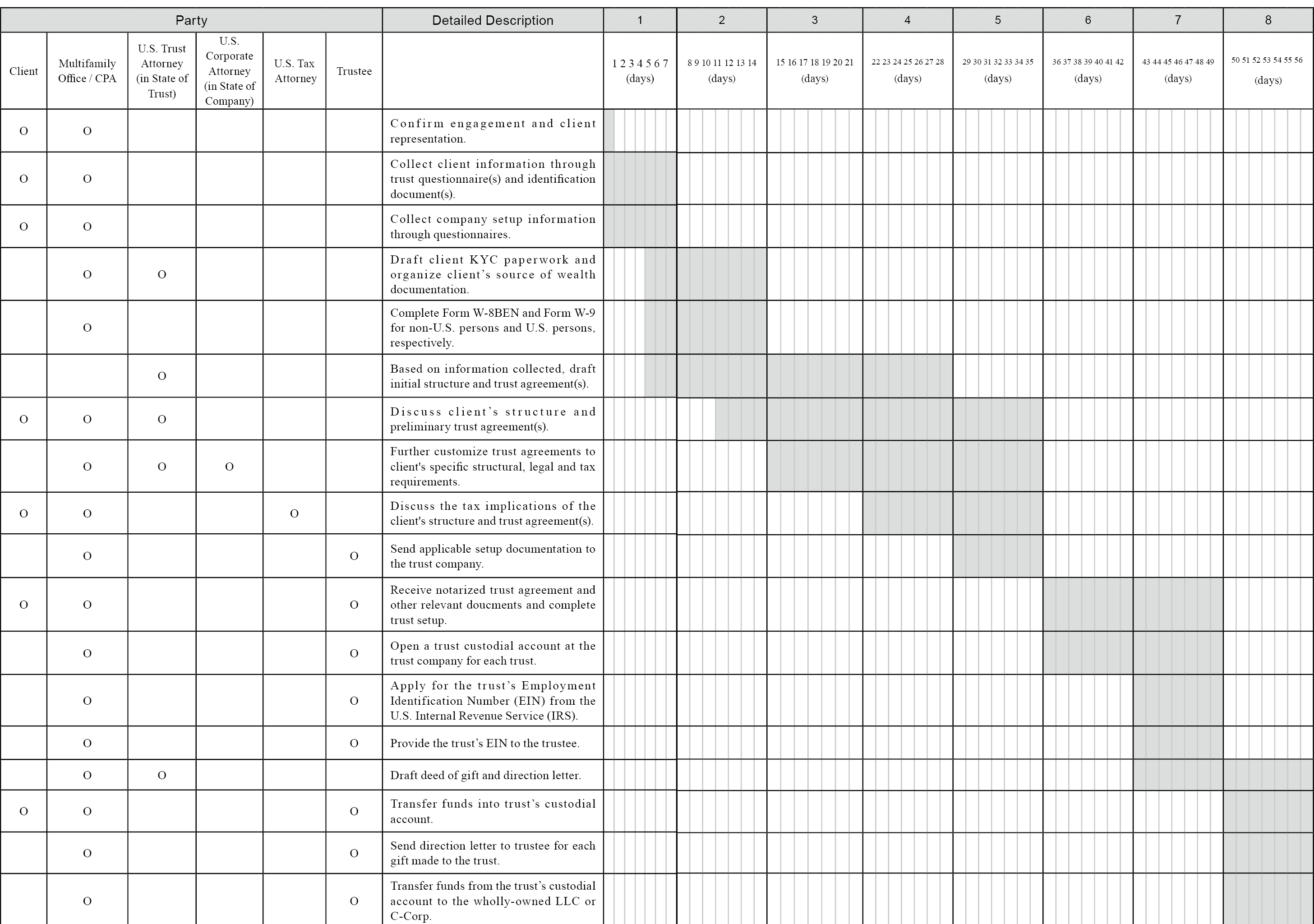

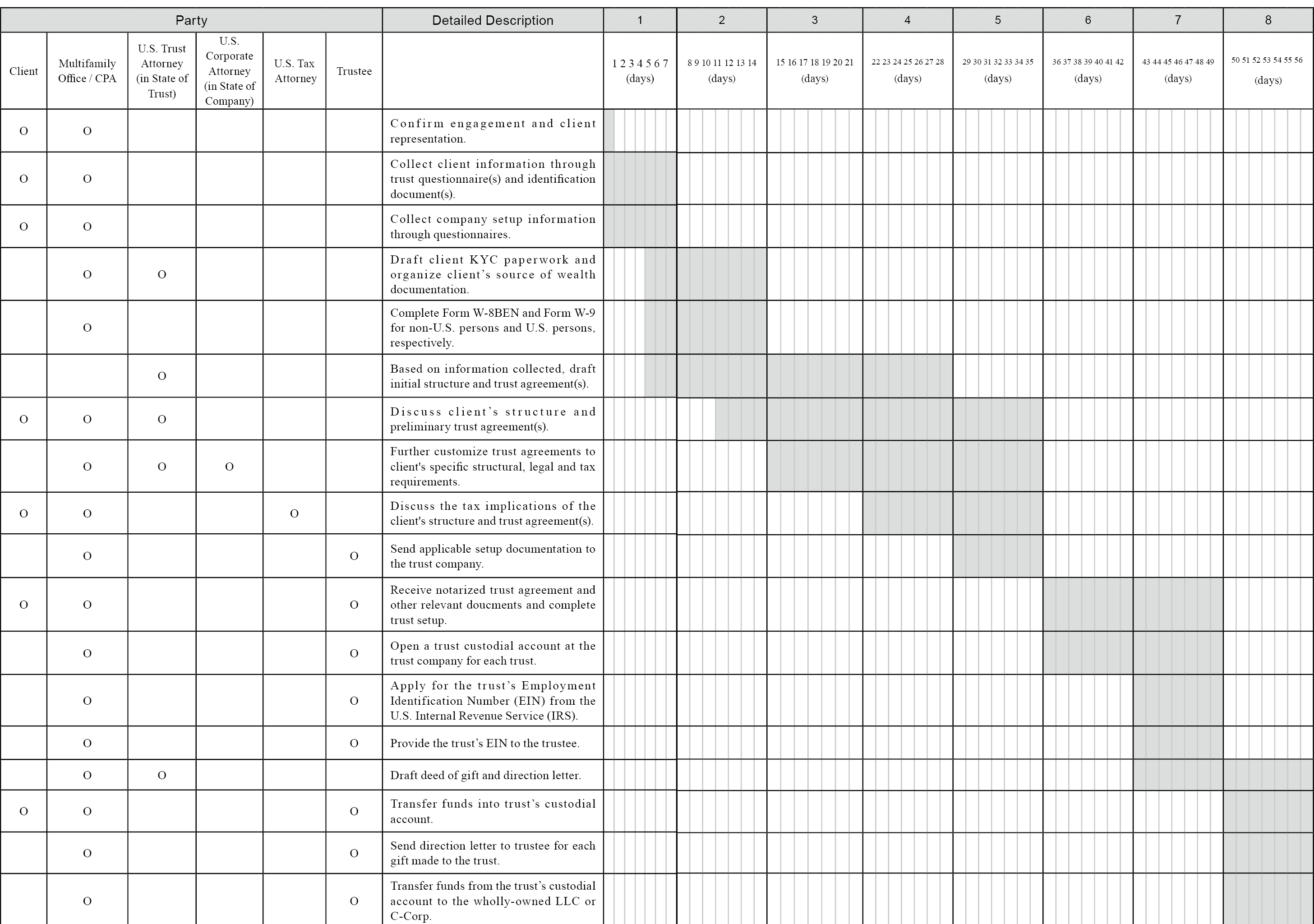

The above chart illustrates the steps necessary to establishing a U.S. irrevocable trust. While each client situation may require substantial customizations, the timeline is generally an estimate of the time each step will take.

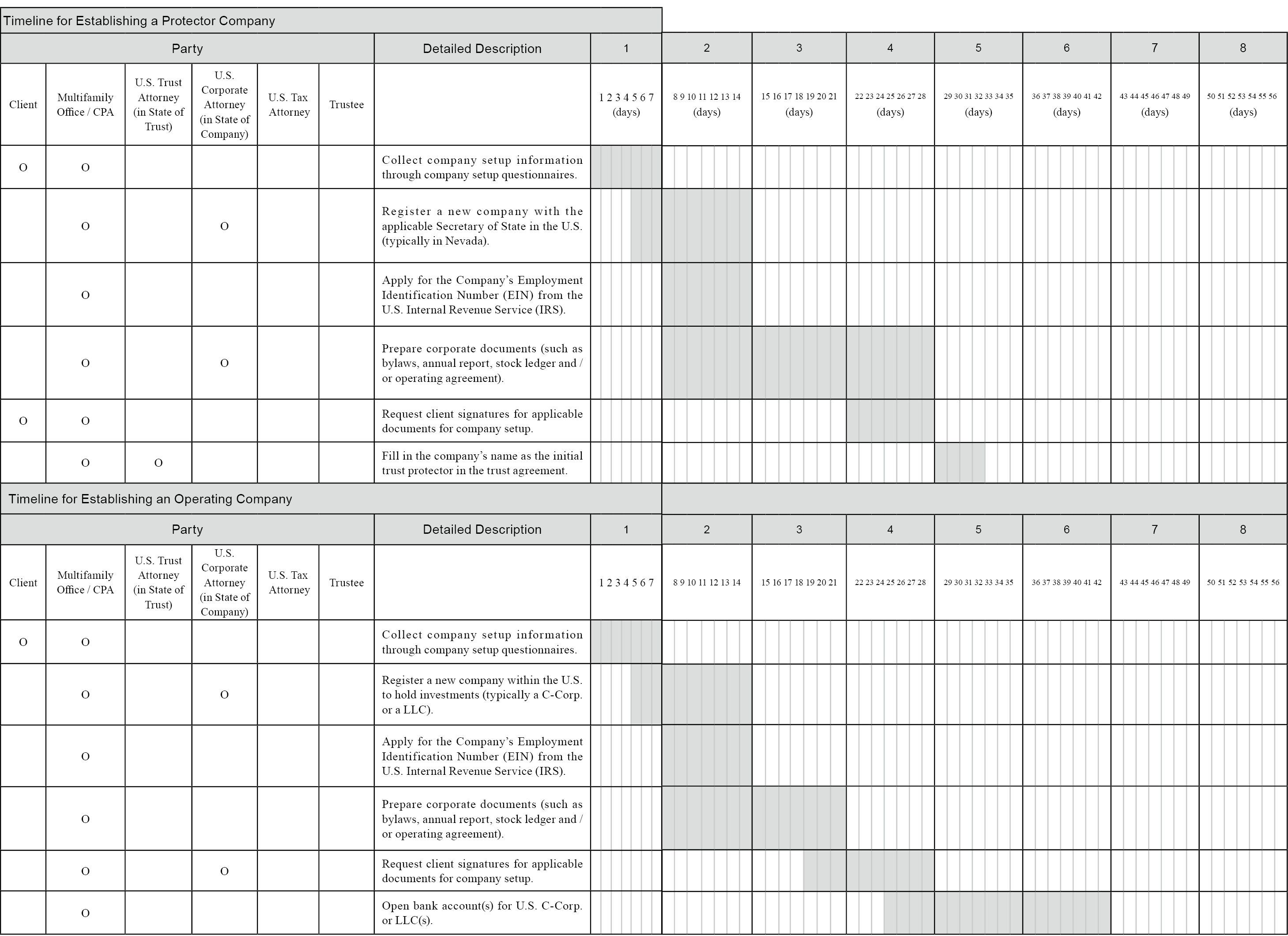

2 – Determining the Roles in a Nevada Irrevocable Trust

When establishing a U.S. trust, the Wealth Creator must take into consideration the roles that must be assigned and their powers in the trust. Generally, a trust has the following roles:

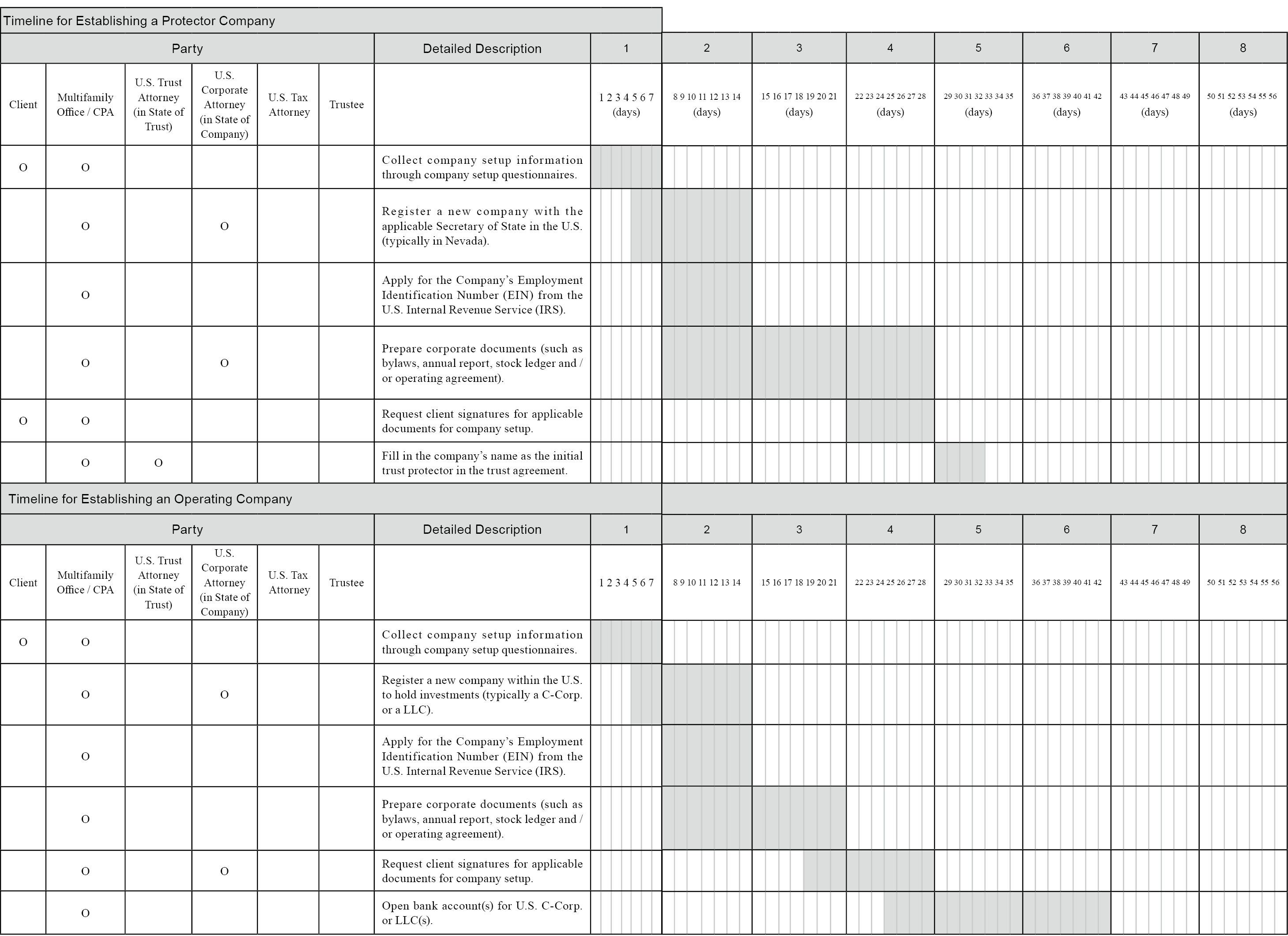

The structure below introduces the trust agreement and the roles defined by a trust agreement:

Most trust agreements are drafted so that each power holder (each of the roles) is independent of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. The main purpose of this independence is to separate the trust assets from the assets of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. By doing so, the structure minimizes the risk of triggering various taxes. Primarily, trust attorney(s) would consider the following factors when determining whether a trust can maintain independence (though other rules may apply for specific situations):

Below, we give an example of roles, powers and responsibilities held by various parties to the trusts:

The Grantor (sometimes referred to as the trust’s Settlor) transfers assets to the trust. Assets transferred can take the form of cash (typically wired from outside the U.S.) or in the form of shares of a non-U.S. company (an offshore company, such as a BVI company or a Cayman Islands company) or a U.S. company (such as a C-Corporation or interest in an LLC). In an irrevocable trust, the Grantor typically does not have any powers that would allow him or her to manage the operations of the trust. In a revocable trust (as discussed in Chapter 3), a Grantor would typically retain the power to revoke the trust and the power to distribute trust assets to any person during his or her lifetime.

The Trust Protector typically holds the most power in the trust, effectively allowing him or her to determine all substantial decisions made by the trust. The Trust Protector’s powers typically include the powers to:

The Distribution Advisor has the power to determine the amount and frequency of distributions to the trust’s beneficiaries. As such, the trust’s beneficiaries are typically forbidden from serving as the trust’s Distribution Advisor.

In many trusts, the Trust Protector also serves as the Investment Direction Advisor and the Distribution Advisor. In many trusts, the Trust Protector may also have the power to determine compensation for the Investment Direction Advisor(s) and Distribution Advisor(s).

When establishing a trust, the trust company typically conducts the most diligence on the grantor. The trustee will typically request the grantor’s basic information, including but not limited to:

In addition, the trustee must also conduct independent diligence on the grantor’s source of wealth. This often involves requesting:

The trustee will also request information regarding the trust’s beneficiaries, typically including:

Lastly, the trustee will request information from the trust’s fiduciaries (including the trust protector, investment direction advisor and distribution advisor). While the trust’s grantor and beneficiaries are required to provide the bulk of the information, the trust’s fiduciaries must also provide certain information and documentation:

3 – Maintaining a Nevada Irrevocable Trust

After the trust agreement is notarized, the Nevada Irrevocable Trust is officially settled. While this is a major milestone in the process, the fiduciaries of the trust (namely, the Protector, Distribution Advisor and Investment Direction Advisor) must now direct the Trustee and the trust’s legal and accounting advisors to maintain and operate the trust. This section gives specific guidance as to how a typical irrevocable trust is operated.

3A – Applying for the Trust’s EIN

In order to perform several basic functions, the trust must apply for an Employee Identification Number (EIN) with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS). After the trust receives an EIN, it can then:

There are three frequently used methods of applying for an EIN:

Note: For a detailed explanation of EIN application, please refer to the section of Chapter 4 that discusses the Form SS-4.

3B – Creating and Funding a Trust Bank Account

Once the trust’s EIN is obtained, the Trustee may set up an account on behalf of the trust. The process usually takes a number of weeks, depending on the Trustee’s familiarity with the client and the clients’ sources of funds. At this stage, KYC (Know Your Client) is typically conducted on the client and the clients’ sources of wealth. After the account is established, the Grantor(s) of the trust will generally be able to wire funds from their personal bank accounts into the trust’s bank account.

If the Grantor wishes to contribute funds held by a closely held business entity, the Grantor would generally be required to distribute the funds to his or her personal account before making a gift to a trust. Wealth Creators who are unable or unwilling to do so should consult with advisors who can provide alternative ways of making the gift.

3C – Creating and Funding a New LLC (held by the Trust)

Upon receiving the Trust’s EIN, the Investment Direction Advisor may direct the Trustee to establish an LLC held by the Trust through a direction letter. The LLC is generally set up as a single-member LLC, meaning that it has a single owner (the Trust). Depending on the state, the LLCs manager(s) may be required to complete additional paperwork.

An LLC’s member is typically an LLC’s legal owner or shareholder. LLCs may be set up as either manager-managed LLCs or member-managed LLCs. In manager-managed LLCs, the decision-making power is held by the managers of the LLC. Managers are usually assigned by the member upon the creation of the LLC. If managers need to be added or replaced, the member generally must sign off on any changes. In member-managed LLCs, the member (owner) is typically in charge of the operations and decision-making of the LLC.

Any decision made by a member-managed LLC that is trust-owned would require the sign off of the Trustee. As such, LLCs held by Directed Trusts are most often manager-managed to maximize operational flexibility and minimize ongoing trustee fees (apart from annual trust fees, many trustees charge a per service or per signature fee). In certain circumstances, the trust’s fiduciaries or even beneficiaries may serve as manager(s) of the trust-owned LLCs.

Once the LLC is established, the LLC’s manager (or member) may fill out an SS-4 Form to apply for the LLC’s EIN. Upon receiving the EIN, the LLC’s manager (or member) can generally create a bank account for the LLC at most U.S. commercial banks.

The funds held in the trust’s bank account can then be transferred into the LLC’s newly created bank account. Prior to completing a funds transfer (especially a larger one), it is typical for the Trustee to require the authentication and authorization of the Trust’s Investment Direction Advisor through email or phone.

Once the LLC’s bank account is funded, the LLC’s manager can proceed to invest the funds in securities, real estate or other investments as he or she deems appropriate. Manager-managed LLC’s investments generally do not require any notification to or approval by the Trustee.

3D – Processing Trust Distributions to Beneficiaries

When a trust makes a distribution to its beneficiaries, the trust can generally do so by distributing (1) the trust’s principal, (2) the trust’s income or (3) a mixture of both. The categorization of income vs. principal is quite complicated and varies depending on a number of factors.

Distributions of a trust’s principal is generally not taxable. Upon receipt of a principal distribution, neither the beneficiary nor the trust would be liable for Federal Income Tax. If the assets in the trust do not appreciate, the trust (and its beneficiaries) would generally not owe income tax.

If the Grantor makes a gift to the trust, the gift would be considered the trust’s principal. If the trust then distributes the principal to the trust’s beneficiaries immediately (prior to the principal appreciating in value or generating any income), the distribution would typically not trigger U.S. income tax.

Generally, when trust income is not distributed to its beneficiaries during a given tax year, the trust must pay income tax on that income. If the trust’s income is paid to the trust’s beneficiaries, the trust itself would not pay income tax on the income distributed. Beneficiaries receiving income distributions from the trust will generally receive a K-1 from the trust, indicating the amount of income received.

Trusts reach the highest federal marginal income tax rate at much lower thresholds than individual taxpayers ($14,451 for trusts vs. $578,126 for individuals in 2023), and therefore generally pay higher Federal income taxes. As such, it is generally advisable that the trust’s fiduciaries evaluate distributing an irrevocable trust’s income to its beneficiaries, as doing so could lower the effective income tax rate.

3E – Complying with Disclosure Requirements

Under U.S. laws and regulations, trusts established in the U.S. must comply with certain income tax and disclosure requirements. These are described in length in Chapter 4.

3G – Transferring Assets from Another Trust

From time to time, Wealth Creators may want to transfer assets from one trust to another trust. While there are many ways of transferring assets, the most common methods are:

(3) Domesticating a trust from one jurisdiction to another jurisdiction.

(4) Dividing one trust into two or more separate trusts (trust division).

By using this structure, the Wealth Creator attains several key benefits, without incurring additional expenses.

(1) The Wealth Creator is able to continue to operate his or her business(es) as if the trust were not created. Even though ownership of the BVI company has already been transferred to the trust, the Wealth Creator can continue to serve as the company’s director and control the company’s operations.

(2) The Wealth Creator is able to make distributions from his or her BVI company to the trust’s non-U.S. beneficiaries, without incurring U.S. income tax. The only form that is required by the U.S. is FINCEN Form 114 (FBAR); additional information regarding the FBAR can be found in Chapter 4.

(3) The Wealth Creator is able to choose the trust’s beneficiaries. After transferring assets into the trust, the assets would no longer be considered part of the Wealth Creator’s estate and thus would generally not be subject to laws that regulate the distribution of one’s estate.

(4) The Wealth Creator is able to choose the trust’s fiduciaries (the trust protector, distribution advisor and investment direction advisor), thereby determining who will have the power to direct the trust after the Wealth Creator’s death.

(5) Since the trust is based in the U.S. (usually in Nevada) and the U.S. does not participate in the Common Reporting Standards (CRS), the trust’s beneficial ownership interest information would not be shared to other countries.

(6) The cost of maintaining the structure is relatively low, generally less than US$10,000 per year. This is significantly lower than most structures created outside of the U.S.

1 – Establishing a Nevada Irrevocable Trust (General Procedures)

While there are numerous benefits to settling an Irrevocable Trust, Wealth Creators, especially non-U.S. ones, often face considerable difficulty when selecting a firm to work with. When non-U.S. Wealth Creators set out to create a trust, they usually must contact the following service providers:

(1) A law firm or attorney that specializes in drafting trust agreements, frequently called the “drafter”

(2) A law firm or attorney that specializes in cross-border taxation and estate planning, usually called the “tax attorney”

(3) An accounting firm or accountant that can assist with specific disclosures, tax forms and tax returns required of the IRS and other U.S. agencies

(4) A secretarial company that can assist with the creation or transfer of offshore or U.S. companies into U.S. trusts

(5) A secretarial company that can work closely with banks in Hong Kong, Singapore or other jurisdictions on transfers of funds into U.S. accounts

Each of these service providers will typically conduct their own due diligence on the clients’ needs, source of funds and any conflicts with existing clients (for the law firms). As a result, many non-U.S. Wealth Creators may find the process quite daunting. This is especially true when the wealth transfer process takes a number of years or when clients have drastic changes in their life circumstances.

The complexities of the structures necessary for non-U.S. persons to optimize their estate planning may also frequently result in miscommunication, delays in the setup process, difficulties in maintaining various holding structures and even the creation of inoperable structures, if the different service providers are communicating directly with the client only and not with each other.

The authors of this book are all managers of a global accounting and law firm headquartered in Taiwan. Over the past decade, we have worked with numerous U.S. and non-U.S. Wealth Creators on creating their succession plans, establishing over 150 trusts. As an integrated firm with offices in the U.S. and licensed professionals across Asia, we provide clients with services encompassing essential functions necessary for planning cross-border wealth transfer.

The above chart illustrates the steps necessary to establishing a U.S. irrevocable trust. While each client situation may require substantial customizations, the timeline is generally an estimate of the time each step will take.

2 – Determining the Roles in a Nevada Irrevocable Trust

When establishing a U.S. trust, the Wealth Creator must take into consideration the roles that must be assigned and their powers in the trust. Generally, a trust has the following roles:

- Trustee (typically a licensed trust company)

- Grantor (otherwise known as Settlor)

- Fiduciaries

- Protector

- Investment Direction Advisor

- Distribution Advisor

- Beneficiaries

The structure below introduces the trust agreement and the roles defined by a trust agreement:

Most trust agreements are drafted so that each power holder (each of the roles) is independent of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. The main purpose of this independence is to separate the trust assets from the assets of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. By doing so, the structure minimizes the risk of triggering various taxes. Primarily, trust attorney(s) would consider the following factors when determining whether a trust can maintain independence (though other rules may apply for specific situations):

1. The trust should be so drafted so that the trust’s grantor(s) and beneficiaries are not allocated powers, that could result in the trust either being treated as a sham trust or being deemed as a certain grantor or beneficiary’s assets for both U.S. income tax purposes and / or U.S. estate tax purposes.

2. In many irrevocable trust agreements, the grantor(s) and beneficiaries of the trust are prohibited from determining the trust’s distributions. Preferably, the current grantor and beneficiaries would not also simultaneously serve as a fiduciary of the trust (the Trust Protector, Investment Direction Advisor or Distribution Advisor), with a few limited exceptions.

3. If the Trust Protector or Distribution Advisor are the legal parents of the trust’s beneficiaries, they should not make distribution to the beneficiaries until the beneficiaries turn 21. Doing so could potentially be deemed as the fiduciary (the parent) using trust assets to replace his or her legal responsibility to raise the child and thus have the trust assets to be deemed as assets of the fiduciary (the parent). This could lead to adverse tax consequences for the trust and / or the fiduciary.

Below, we give an example of roles, powers and responsibilities held by various parties to the trusts:

The Grantor (sometimes referred to as the trust’s Settlor) transfers assets to the trust. Assets transferred can take the form of cash (typically wired from outside the U.S.) or in the form of shares of a non-U.S. company (an offshore company, such as a BVI company or a Cayman Islands company) or a U.S. company (such as a C-Corporation or interest in an LLC). In an irrevocable trust, the Grantor typically does not have any powers that would allow him or her to manage the operations of the trust. In a revocable trust (as discussed in Chapter 3), a Grantor would typically retain the power to revoke the trust and the power to distribute trust assets to any person during his or her lifetime.

The Trust Protector typically holds the most power in the trust, effectively allowing him or her to determine all substantial decisions made by the trust. The Trust Protector’s powers typically include the powers to:

- Replace the trust’s trustee.

- Add charitable beneficiaries.

- Direct a decanting of the trust’s assets.

- Direct a division of the trust into separate trusts (held for the same or different beneficiaries).

- Add individual beneficiaries (subject to certain limitations).

- Change the trust’s jurisdiction (subject to certain limitations).

- Assign a successor trust protector, upon the resignation or passing of the Trust Protector.

- Add, remove, or replace the trust’s Investment Direction Advisor(s) or Distribution Advisor(s).

The Distribution Advisor has the power to determine the amount and frequency of distributions to the trust’s beneficiaries. As such, the trust’s beneficiaries are typically forbidden from serving as the trust’s Distribution Advisor.

In many trusts, the Trust Protector also serves as the Investment Direction Advisor and the Distribution Advisor. In many trusts, the Trust Protector may also have the power to determine compensation for the Investment Direction Advisor(s) and Distribution Advisor(s).

When establishing a trust, the trust company typically conducts the most diligence on the grantor. The trustee will typically request the grantor’s basic information, including but not limited to:

- a copy of the grantor’s passport and identification card.

- the grantor’s current address.

- the grantor’s phone number.

- the grantor’s email.

- the name of the grantor’s spouse.

- the grantor’s place of birth.

- the grantor’s citizenship or permanent residency (including those with dual residency or dual nationalities).

In addition, the trustee must also conduct independent diligence on the grantor’s source of wealth. This often involves requesting:

- a statement regarding the grantor’s intent and the trust’s purpose. The statement should include how frequently the trust will distribute to its beneficiaries and the nature of such distributions (income or principal).

- the grantor’s employer.

- the grantor’s job title.

- a list of companies that the grantor currently owns or manages.

- the value of assets that will be transferred into the trust.

- the grantor’s resume or CV is required

- the grantor’s education and or employment background.

- a written statement of the grantor’s source(s) of wealth:

- If inheritance or gift, the statement should name the grantor’s giftor or ascendant and their source(s) of wealth.

- If investment, the statement should include detailed information regarding the type and market value of the investments (if current) or date of sale and total proceeds (if past). The statement should explain when and how the investment was made.

- If operating company, the statement should include the name of the business and a general description of the business.

- if anyone other than the grantor were to fund the trust, the trustee would ask for information regarding the additional grantor’s source(s) of wealth.

The trustee will also request information regarding the trust’s beneficiaries, typically including:

- a copy of the beneficiary’s passport and identification card.

- a copy of the beneficiary’s social security card (if available).

- the beneficiary’s place of birth.

- the beneficiary’s current address (a U.S. one, if available).

- the beneficiary’s phone number (a U.S. one if available).

- the beneficiary’s email.

- the beneficiary’s green card issuance date (if one has been issued).

- the beneficiary’s citizenship or permanent residency (including those with dual residency or dual nationalities).

Lastly, the trustee will request information from the trust’s fiduciaries (including the trust protector, investment direction advisor and distribution advisor). While the trust’s grantor and beneficiaries are required to provide the bulk of the information, the trust’s fiduciaries must also provide certain information and documentation:

- a copy of the fiduciary’s passport and identification card.

- a copy of the fiduciary’s social security card (if available).

- the fiduciary’s current address (a U.S. one, if available).

- the fiduciary’s phone number (a U.S. one if available).

- the fiduciary’s email.

3 – Maintaining a Nevada Irrevocable Trust

After the trust agreement is notarized, the Nevada Irrevocable Trust is officially settled. While this is a major milestone in the process, the fiduciaries of the trust (namely, the Protector, Distribution Advisor and Investment Direction Advisor) must now direct the Trustee and the trust’s legal and accounting advisors to maintain and operate the trust. This section gives specific guidance as to how a typical irrevocable trust is operated.

3A – Applying for the Trust’s EIN

In order to perform several basic functions, the trust must apply for an Employee Identification Number (EIN) with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS). After the trust receives an EIN, it can then:

(1) open U.S. bank account(s)

(2) establish and own U.S. companies (typically LLCs and C-Corporations)

(3) file annual tax filings with the IRS

There are three frequently used methods of applying for an EIN:

(1) by completing an online application

(2) by completing an application and faxing it to the IRS

(3) by calling the IRS directly and applying over the phone

Note: For a detailed explanation of EIN application, please refer to the section of Chapter 4 that discusses the Form SS-4.

3B – Creating and Funding a Trust Bank Account

Once the trust’s EIN is obtained, the Trustee may set up an account on behalf of the trust. The process usually takes a number of weeks, depending on the Trustee’s familiarity with the client and the clients’ sources of funds. At this stage, KYC (Know Your Client) is typically conducted on the client and the clients’ sources of wealth. After the account is established, the Grantor(s) of the trust will generally be able to wire funds from their personal bank accounts into the trust’s bank account.

If the Grantor wishes to contribute funds held by a closely held business entity, the Grantor would generally be required to distribute the funds to his or her personal account before making a gift to a trust. Wealth Creators who are unable or unwilling to do so should consult with advisors who can provide alternative ways of making the gift.

3C – Creating and Funding a New LLC (held by the Trust)

Upon receiving the Trust’s EIN, the Investment Direction Advisor may direct the Trustee to establish an LLC held by the Trust through a direction letter. The LLC is generally set up as a single-member LLC, meaning that it has a single owner (the Trust). Depending on the state, the LLCs manager(s) may be required to complete additional paperwork.

An LLC’s member is typically an LLC’s legal owner or shareholder. LLCs may be set up as either manager-managed LLCs or member-managed LLCs. In manager-managed LLCs, the decision-making power is held by the managers of the LLC. Managers are usually assigned by the member upon the creation of the LLC. If managers need to be added or replaced, the member generally must sign off on any changes. In member-managed LLCs, the member (owner) is typically in charge of the operations and decision-making of the LLC.

Any decision made by a member-managed LLC that is trust-owned would require the sign off of the Trustee. As such, LLCs held by Directed Trusts are most often manager-managed to maximize operational flexibility and minimize ongoing trustee fees (apart from annual trust fees, many trustees charge a per service or per signature fee). In certain circumstances, the trust’s fiduciaries or even beneficiaries may serve as manager(s) of the trust-owned LLCs.

Once the LLC is established, the LLC’s manager (or member) may fill out an SS-4 Form to apply for the LLC’s EIN. Upon receiving the EIN, the LLC’s manager (or member) can generally create a bank account for the LLC at most U.S. commercial banks.

The funds held in the trust’s bank account can then be transferred into the LLC’s newly created bank account. Prior to completing a funds transfer (especially a larger one), it is typical for the Trustee to require the authentication and authorization of the Trust’s Investment Direction Advisor through email or phone.

Once the LLC’s bank account is funded, the LLC’s manager can proceed to invest the funds in securities, real estate or other investments as he or she deems appropriate. Manager-managed LLC’s investments generally do not require any notification to or approval by the Trustee.

3D – Processing Trust Distributions to Beneficiaries

When a trust makes a distribution to its beneficiaries, the trust can generally do so by distributing (1) the trust’s principal, (2) the trust’s income or (3) a mixture of both. The categorization of income vs. principal is quite complicated and varies depending on a number of factors.

Distributions of a trust’s principal is generally not taxable. Upon receipt of a principal distribution, neither the beneficiary nor the trust would be liable for Federal Income Tax. If the assets in the trust do not appreciate, the trust (and its beneficiaries) would generally not owe income tax.

If the Grantor makes a gift to the trust, the gift would be considered the trust’s principal. If the trust then distributes the principal to the trust’s beneficiaries immediately (prior to the principal appreciating in value or generating any income), the distribution would typically not trigger U.S. income tax.

Generally, when trust income is not distributed to its beneficiaries during a given tax year, the trust must pay income tax on that income. If the trust’s income is paid to the trust’s beneficiaries, the trust itself would not pay income tax on the income distributed. Beneficiaries receiving income distributions from the trust will generally receive a K-1 from the trust, indicating the amount of income received.

Trusts reach the highest federal marginal income tax rate at much lower thresholds than individual taxpayers ($14,451 for trusts vs. $578,126 for individuals in 2023), and therefore generally pay higher Federal income taxes. As such, it is generally advisable that the trust’s fiduciaries evaluate distributing an irrevocable trust’s income to its beneficiaries, as doing so could lower the effective income tax rate.

3E – Complying with Disclosure Requirements

Under U.S. laws and regulations, trusts established in the U.S. must comply with certain income tax and disclosure requirements. These are described in length in Chapter 4.

3G – Transferring Assets from Another Trust

From time to time, Wealth Creators may want to transfer assets from one trust to another trust. While there are many ways of transferring assets, the most common methods are:

(1) Selling the assets from one trust to another trust.

When selling assets from one trust to another trust, Wealth Creators must make note of which asset type they are selling. For example, if the trust is selling real estate, the trust would ordinarily require the services of a title company; however, if the trust is selling the LLC that owns the real estate, the transaction is significantly simpler and can be structured as a sale of the LLC interest itself. In the U.S., the sale of certain assets generally involves a purchase agreement. In addition, the buyer would ordinarily be making the payment to the previous owner of the asset. In most situations, it is advisable for attorneys, CPAs, appraisers and / or business valuation experts to give advice regarding the value of the assets being sold.

(2) Decanting the assets from one trust to another trust.

When decanting assets from one trust to another, Wealth Creators must communicate their needs to their advisors and trustee(s). Decanting often involves a direct transfer of ownership interest from one trust to another trust. Depending on the trust and the jurisdiction, decanting assets may or may not be possible. While it is possible to decant assets from a non-U.S. trust to a U.S. trust, this can prove to be quite cumbersome and may require certain approvals and indemnities. In some situations, the Trust Protector may be able to decant assets from one trust to another trust as a way to amend certain unfavorable terms of the original trust agreement.

(3) Domesticating a trust from one jurisdiction to another jurisdiction.

In certain situations, the Wealth Creator may want to change trust jurisdictions but continue to use the same trust agreement. In this case, the Wealth Creator can consider domesticating a non-U.S. trust or changing the trust’s jurisdiction from one U.S. state to another U.S. state.

(4) Dividing one trust into two or more separate trusts (trust division).

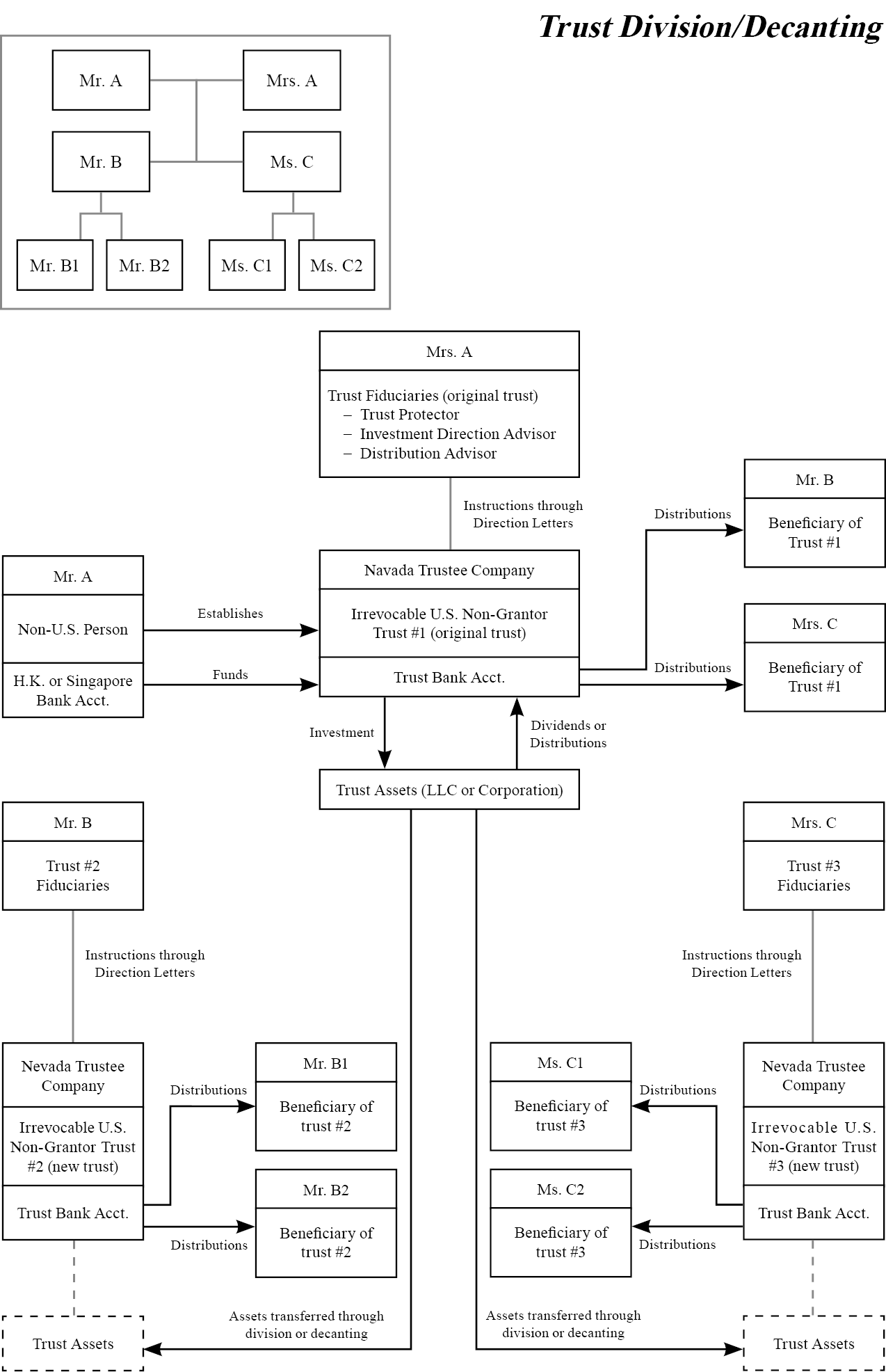

Many trusts are designed with more than one beneficiary in mind. When the Trust Protector deems that the different beneficiaries of the trust would be served by two separate sets of fiduciaries, the Trust Protector should consider dividing the original trust. This is most commonly done if the beneficiaries of the trust consist of more than one family unit. The chart below illustrates a division in action.

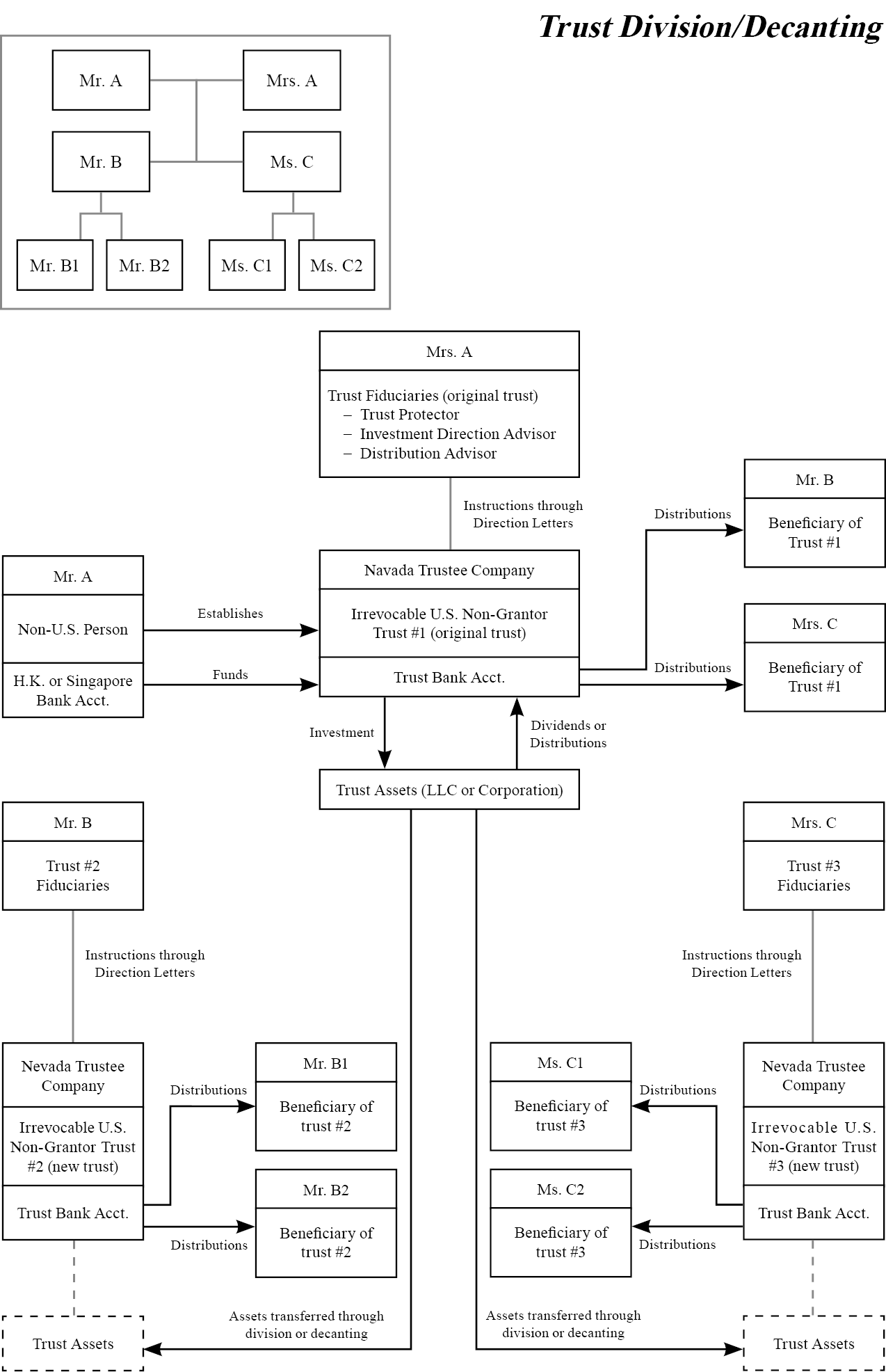

Irrevocable Life Insurance Trusts (ILITs) are a popular estate planning tool in the United States, especially for high-net-worth individuals seeking to minimize estate taxes and provide liquidity for their estates. An ILIT is an irrevocable trust that contains provisions specifically designed to facilitate the ownership of insurance policies.

The ILIT is the owner and the beneficiary of the life insurance policy. If the trust is structured and managed properly, the life insurance death benefit received by the ILIT will not be subject to income or estate tax upon the insured’s death.

Non-U.S. Wealth Creators with U.S. descendants should consider naming a U.S. irrevocable dynasty trust as their ILIT’s beneficiary. When structured properly, this can generally effectively shield proceeds from the life insurance policy both from U.S. gift and estate taxation and creditors of the beneficiaries.

During the grantor’s life, the trustee will often hold certain powers (including the power to distribute). Upon the grantor’s death, distributions will be made according to the trust agreement’s terms.

Benefits of ILITs

1. Estate Tax Mitigation: Non-U.S. persons with U.S.-based assets may still be subject to U.S. estate taxes. U.S. persons with assets above the lifetime gift and estate tax exemption would generally also be subject to U.S. estate taxes. An ILIT can help reduce the taxable estate by removing the life insurance policy from the individual's estate.

2. Asset Protection: ILITs can provide a level of protection for assets against creditors.

3. Liquidity: Life insurance proceeds can provide liquidity to pay estate taxes, debts, and other expenses without the need to sell other assets.

Key Non-Tax Considerations

1. U.S. Situs Assets: Non-U.S. persons owning U.S.-situs assets, such as real estate or tangible personal property located in the U.S., may benefit from using an ILIT to minimize U.S. estate tax exposure.

2. Trustee Selection: The choice of trustee is critical. The trustee can generally be anyone other than the insured person. Naming an “independent trustee,” such as a third-party independent trust company, may offer greater flexibility for estate planning.

3. Compliance and Reporting: ILITs established by non-U.S. persons may have additional compliance requirements, including reporting under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR) regulations.

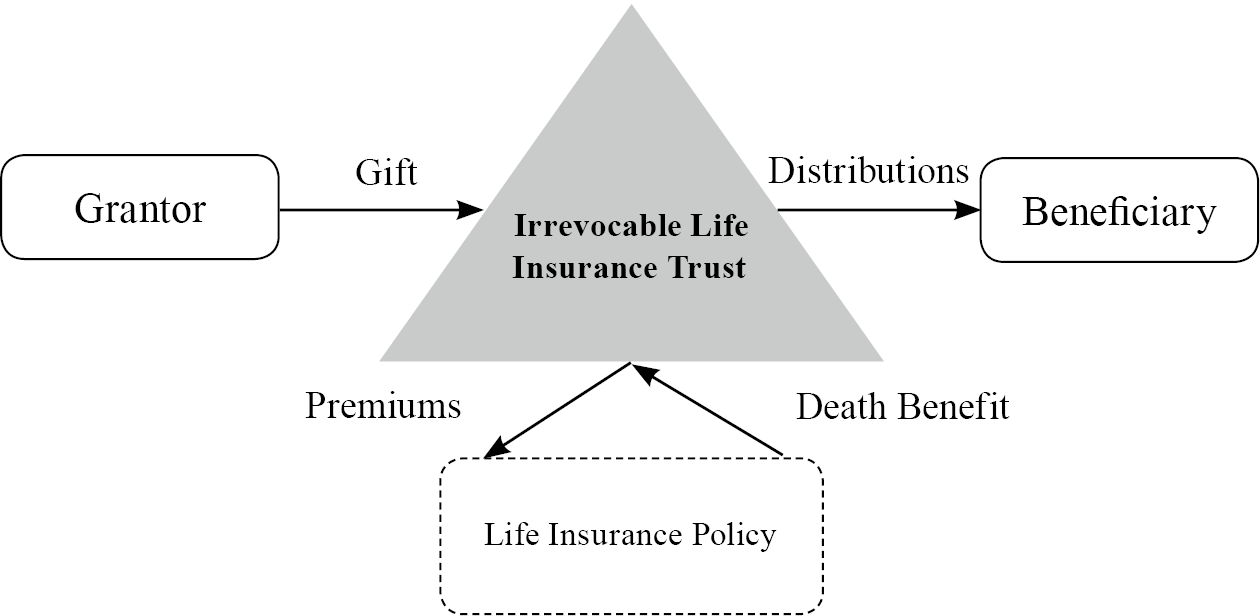

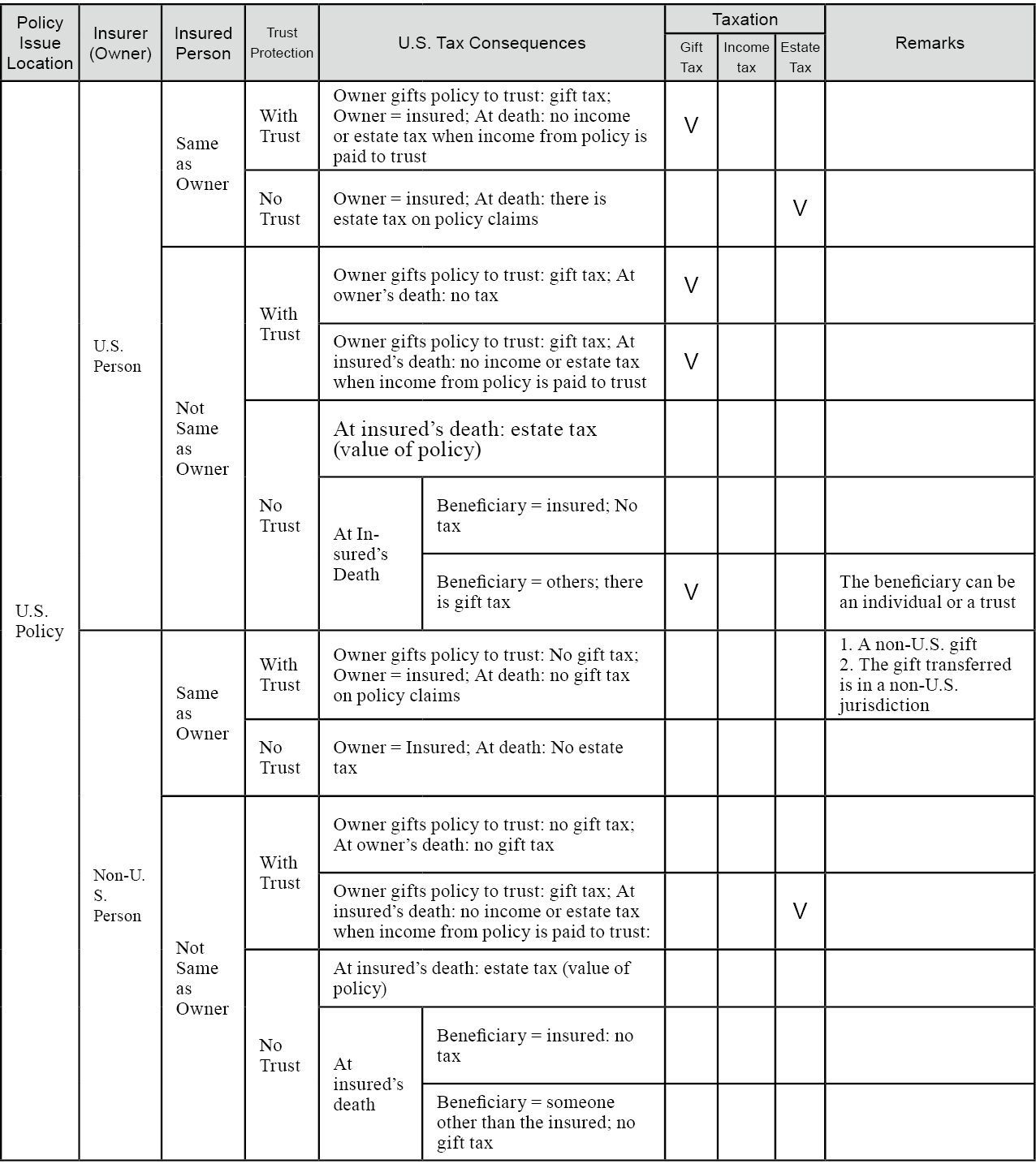

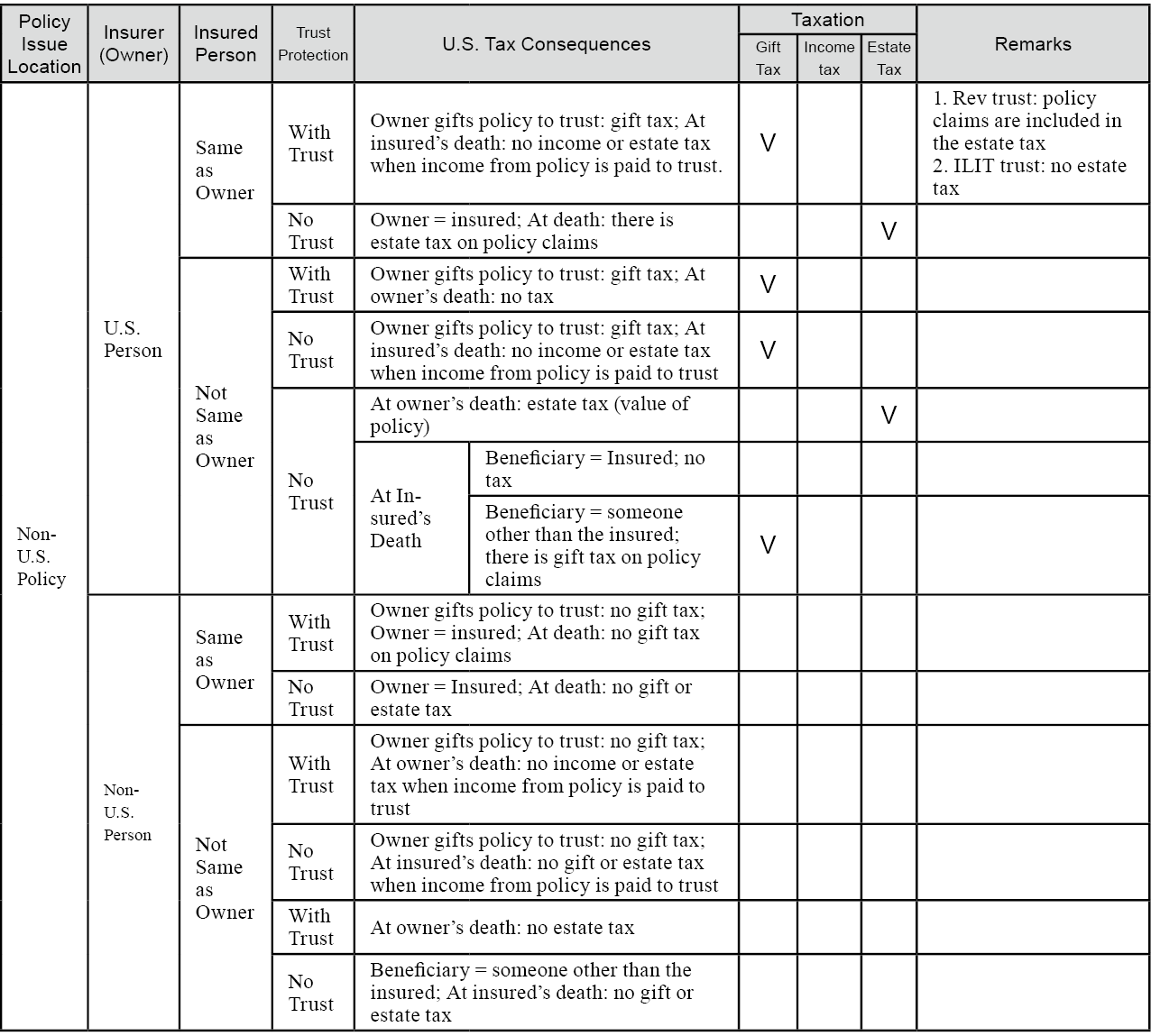

Key Tax Considerations for U.S. Policies

Key Tax Considerations for Non-U.S. Policies

Structuring the ILIT

1. Establishing the Trust: The ILIT must be properly drafted, typically under the laws of a jurisdiction that is favorable for trust creation, such as Nevada. As an ILIT is treated as a separate entity, it apply for its own separate taxpayer identification number (typically referred to as an “EIN” or “FEIN”). All policies purchased in the name of the ILIT or transferred to the ILIT should reference the ILIT’s taxpayer identification number (and not the insured’s social security number) on the ownership and beneficiary forms for the life insurance policy.

2. Funding the Trust: Gifting cash or other assets to an ILIT is a common and simple funding method. U.S. persons often need to consider their lifetime gift exemptions ($13.6 million per person in 2024). When funded properly, non-U.S. persons can make gifts to an ILIT free of U.S. gift tax.

3. Crummey Powers: To ensure that contributions to the trust qualify for the annual gift tax exclusion, the trust can include Crummey powers, allowing beneficiaries to withdraw contributions for a limited time. U.S. persons can generally make gifts of $18,000 to each beneficiary of the trust (in 2024) without using their lifetime gift exemptions.

Conclusion

ILITs can be a valuable tool for both U.S. and non-U.S. persons with significant assets. When purchasing a life insurance, always consult with your financial, legal and tax advisors to see if the policy is a good fit for your needs.