專業叢書

Estate Planning by U.S. Trust 美國報稅與海外財產揭露(英文部分)

Chapter 3 ─ U.S. Dynasty Trusts

Section 3: Types of U.S. Trusts

1. Irrevocable trusts

An irrevocable trust is a trust that the grantor cannot revoke, upon settling the trust. The grantor, having irrevocably transferred ownership of his or her assets into the trust, is no longer the legal owner of the property transferred. Usually, a trust agreement is so structured so that assets transferred to an irrevocable trust are not includible in the grantor’s estate.

If the beneficiary (or beneficiaries) is a U.S. person(s) and the Wealth Creator intends permanently transfer his or her assets into the U.S., a U.S. irrevocable trust may be an effective tool. Once transferred to the U.S. trust, the trust agreement would usually indicate that the U.S. (and the state in which the trust is settled) is the governing jurisdiction. Hence, assets placed in a U.S. trust is generally protected by U.S. laws. First, you must understand that if the assets are producing income in the U.S., income tax consequences are generally the same whether the trust be revocable or irrevocable. Where a trust is properly structured, tax consequences are lighter for non-U.S. persons, when compared to their U.S. counterparts. However, if a foreign grantor places U.S. situs assets for estate tax purposes in a revocable trust, his or her descendants may be subject to high U.S. estate taxes. This is especially given the fact that non-U.S. persons generally have a significantly lower estate tax exemption threshold than U.S. persons.

As a mainstay for many wealthy families in the U.S., Delaware has promoted itself as being one of the most “trust friendly” states. In 1986, Delaware abolished its rule against perpetuities in its entirety, allowing Delaware trusts to retain, invest and reinvest assets and income in perpetuity. Also, while a grantor is unable to revoke an irrevocable trust, the trust’s assets may be “decanted” into another trust. Despite limitations, decanting can often be used as a tool to amend the trust. In addition, the trustee of an irrevocable trust can apply to the Delaware Chancery Court to modify its clauses to meet the needs of the beneficiaries.5

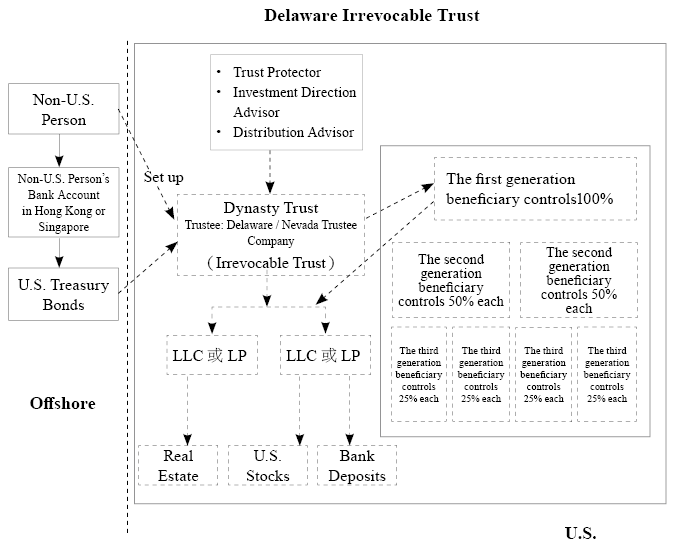

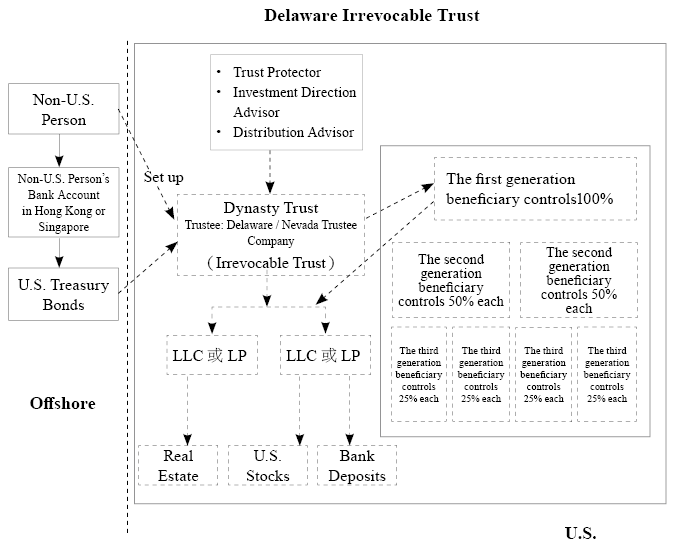

Please see below for an illustrative Delaware irrevocable trust structure:

5 Top Ten Reasons to have your Trust Administered in Delaware

https://library.wilmingtontrust.com/wealth-planning/top-ten-reasons-to-have-your-trust-administered-in-delaware

The above trust is settled by a non-U.S. person in Delaware. A local corporate trustee company is selected to be the trust’s trustee. The trust’s beneficiaries, designated by the grantor, are all U.S. persons. The trust invests in numerous LLCs or LPs, which in turn owns U.S. stocks, bank deposits and real estate.

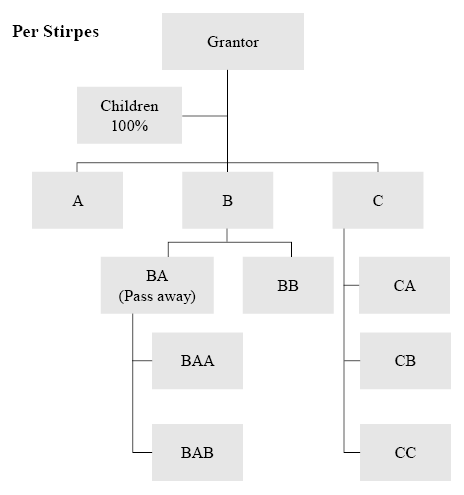

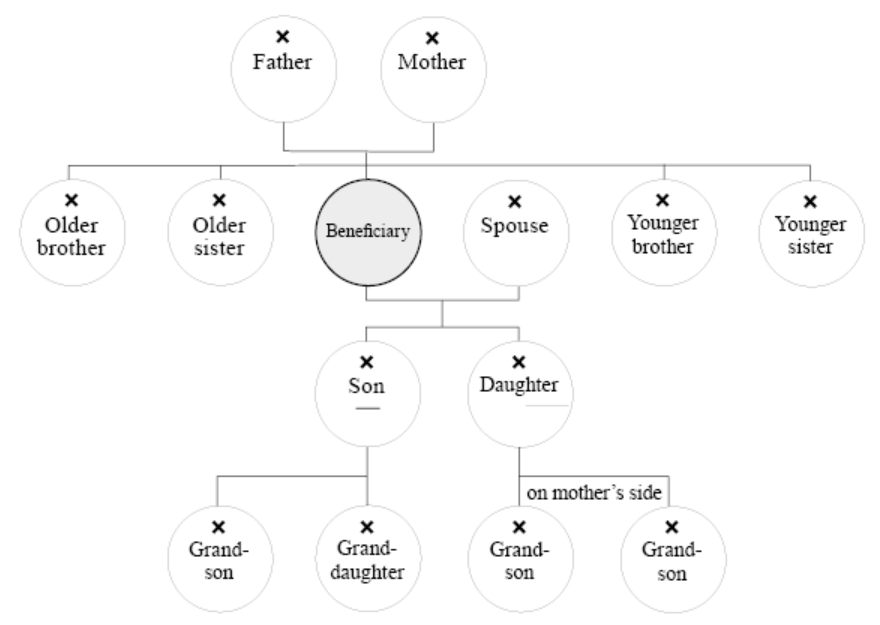

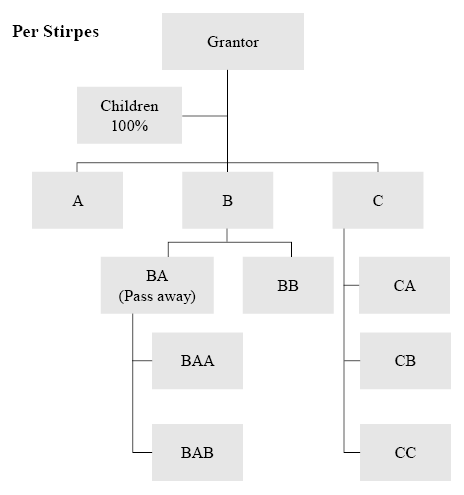

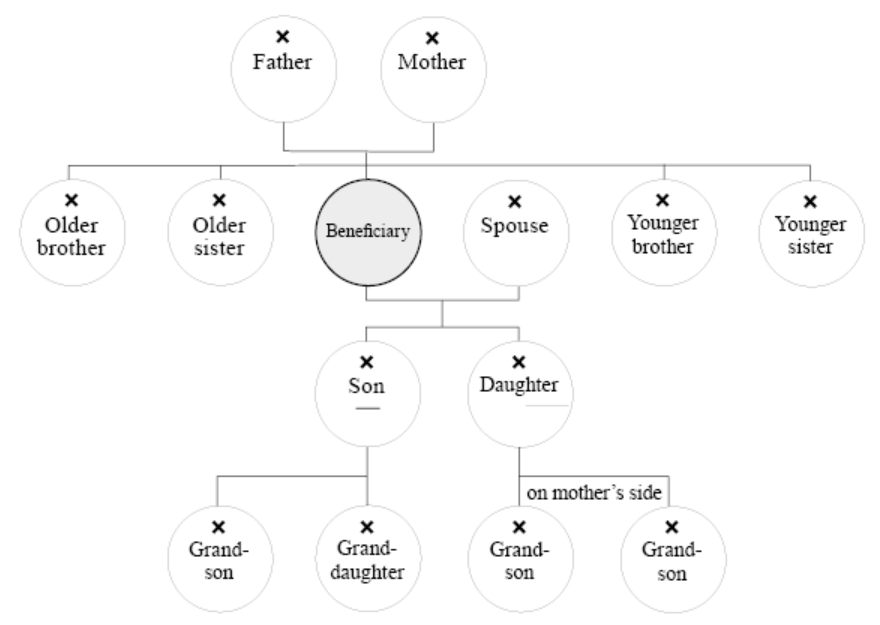

Many families that settle irrevocable trusts incorporate the concept of “per stirpes.” Generally, this means that each descendant of the grantor receives an equal amount of trust assets if the trust were to be divided in the future. The descendants of each of the grantor’s descendants would also receive an equal share of the trust’s assets left to them by their parents.

Generally, under this structure, if a beneficiary passes away with descendants, the beneficiary’s descendants would receive an equal share of that beneficiary’s share of the trust’s assets. If the beneficiary does not have descendants upon his or her death, the trust’s assets apportioned to that beneficiary would then be distributed among the beneficiaries’ siblings (or their descendants), per stirpes. Lastly, if the deceased beneficiary has no descendants or siblings upon his or her death, the assets apportioned to the deceased beneficiary would then be distributed among the deceased beneficiaries’ parents’ siblings (and their descendants), per stirpes, assuming that the deceased beneficiaries’ parents have already passed away.

The following generally indicates whether a U.S. irrevocable trust would be suitable for the Wealth Creator.

(1) The Grantor (generally, the Wealth Creator) does not have the intention of immigrating to the U.S.

If structured correctly, a transfer of assets to a U.S. irrevocable trust can be deemed a completed gift for U.S. tax purposes. If a non-U.S. person transfers non-U.S. situs assets for gift tax purposes into a U.S. irrevocable trust, there is U.S. gift taxes will generally not be owed by the grantor. Generally, the Trustee will file a 3520 Form in the calendar year after the year the gift was consummated to disclose that the trust has received assets from a non-U.S. person.

However, if the grantor is a U.S. person, then the gift of assets would trigger U.S. gift taxes if the gift exceeds the individual’s lifetime gift and estate tax exemption, subject to certain conditions, disregarding whether the assets are U.S. or non-U.S. situs for gift tax purposes.

(2) When foreign assets enter the U.S., the future assets can be used for investment, receiving fructus and distributing income in the U.S. for a long period of time.

The foreign assets will receive asset protection after it has entered the U.S. irrevocable trust for a specific number of years. The year limit of asset protection differs in every state. In Nevada, the assets will receive protection after it has entered the trust for two years. For example, the trust assets can be protected from the claim of creditor, claim of distribution of Marital Property or lawsuit and thus when the future principle of the trust distributes to the beneficiaries, it will not result in transfer taxes such as estate or gift taxes. The fructus or principle accumulated under trust assets will be subject to income tax under the U.S. tax laws.

(3) Gifting assets to an irrevocable trust could prevent inheritance disputes.

Once the irrevocable trust is established, the management of assets held by the trust should follow instructions set forth by the trust agreement. Trust agreements must be drafted (or at least reviewed) by an attorney licensed to practice law in the state the trust is settled. Since the settling of the trust requires a notary and witnesses, it is unlikely that the trust is subject to disputes regarding the legitimacy of the trust. When compared to most wills, a trust agreement is more thorough and is generally more capable of withstanding legal scrutiny.

(4) Transfer taxes including estate, gift and generation-skipping taxes, are minimized or eliminated altogether if the grantor is a non-U.S. person.

U.S. individuals are usually subject to estate taxes, gift taxes and / or generation-skipping taxes (GST) upon the transfer of substantial assets from one generation to the next. Generally, “substantial assets” is defined by the estate and gift tax exemption (and the GST exemption) at the time of the transfer. For non-U.S. persons, a properly structured dynasty trust may prevent assets held by the trust from ever facing U.S. transfer taxes.

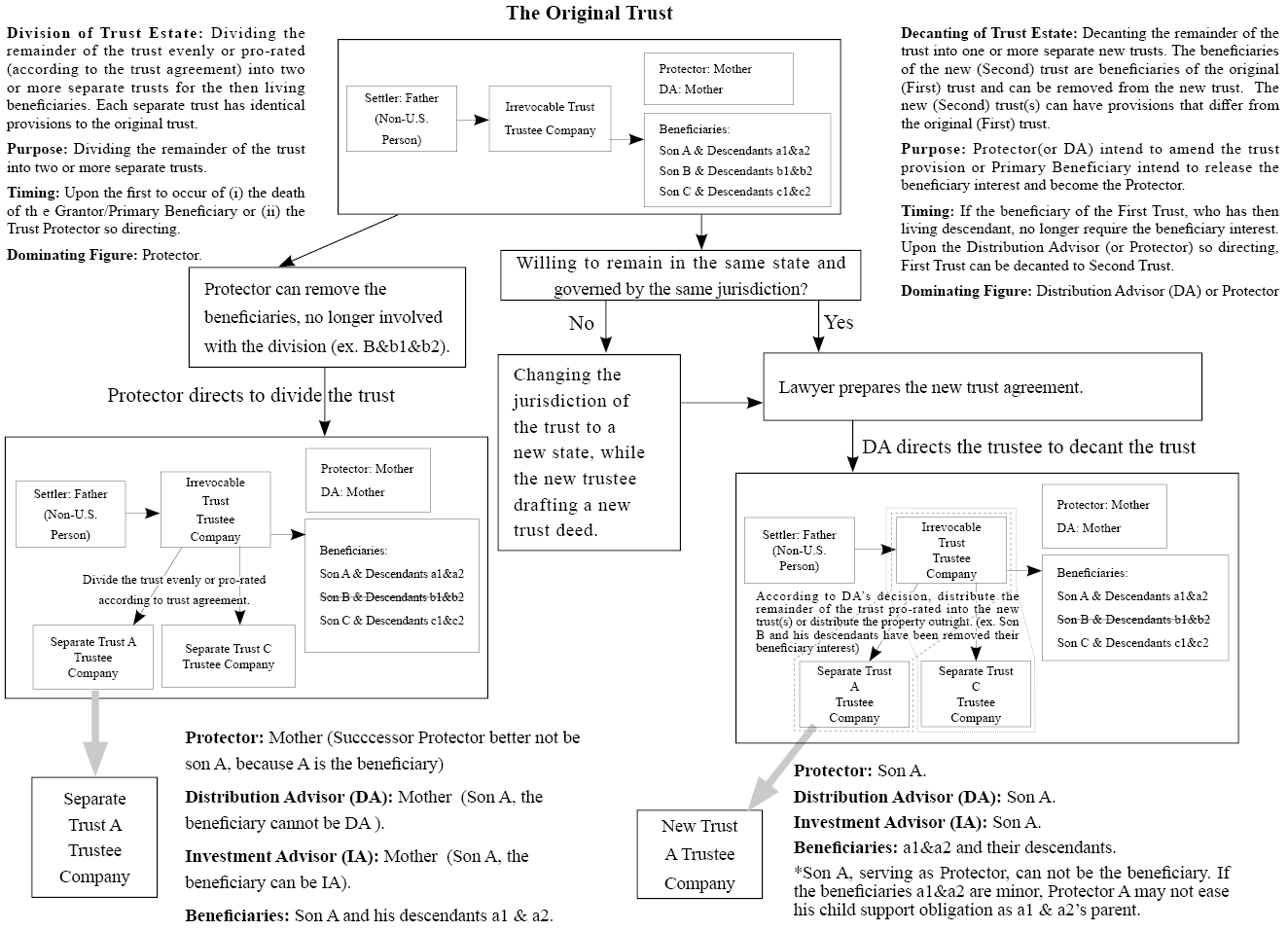

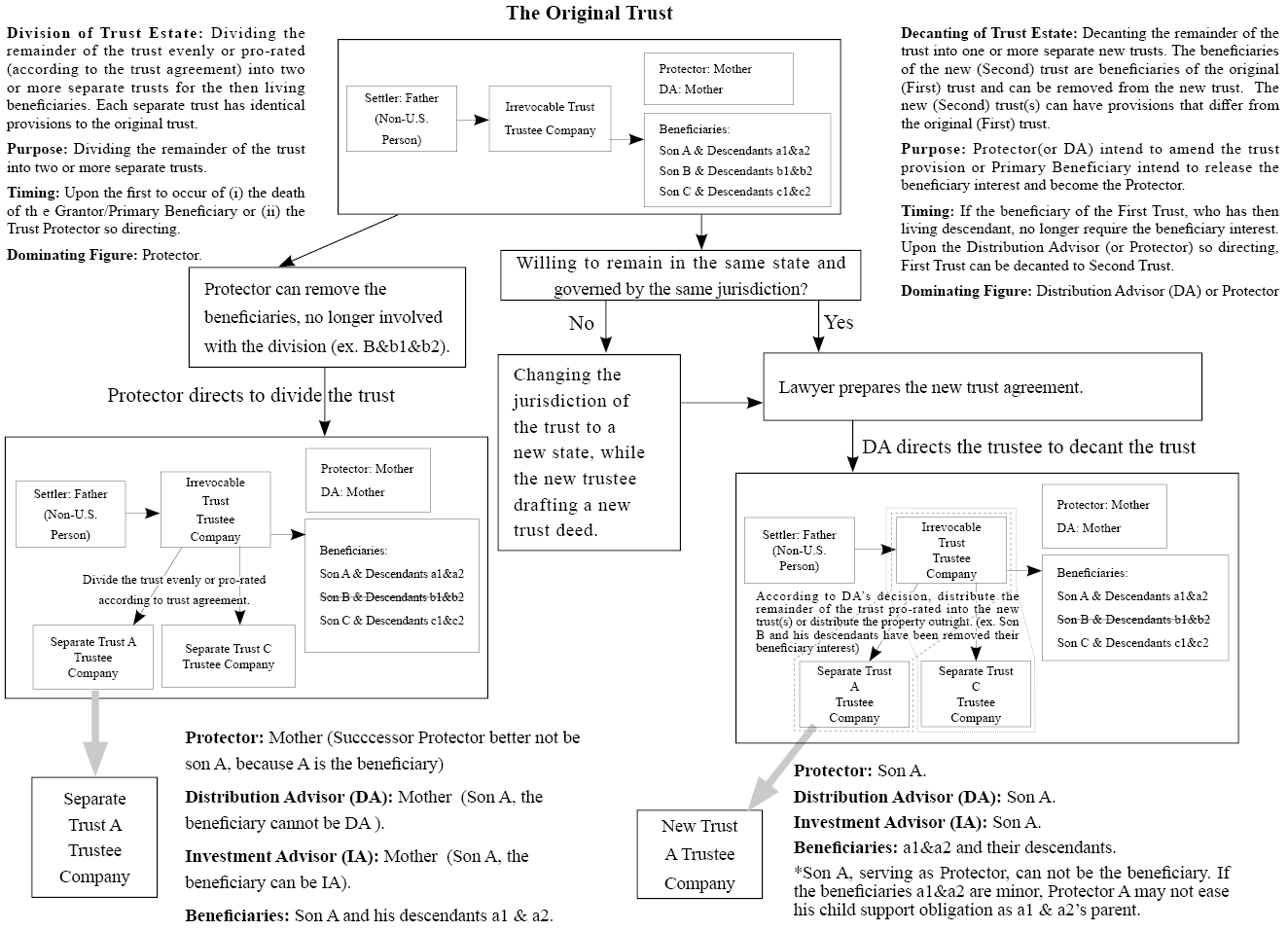

To avoid the double taxation during the assets transfer, the family could pass on the assets to the next generation by means of “division” and “decanting” within the irrevocable trust. (Please refer to the next page.)

(5) Gifting assets to an irrevocable trust could prevent creditors (including spouses, in cases of a marriage dissolution) of the trust’s grantor or beneficiaries from claiming the trust assets.

Once assets are transferred to an irrevocable trust, the trust then becomes the owner of those assets from that point onwards. Among the myriad of reasons to settle an irrevocable trust, asset protection is one of the most important considerations for many Wealth Creators. When properly drafted and operated legitimately, the trust agreement and the trust’s jurisdiction can pose considerable difficulties for any potential creditors.

2. U.S. Revocable Trusts

Generally, revocable trusts are drafted so that the grantor is able to revoke the trust or amend the trust’s provisions at his or her discretion without any third party consent. After transferring assets into revocable trust, the grantor can generally distribute any principal and / or income to the trust’s beneficiaries or to himself without triggering any transfer tax consequences. For Wealth Creators who wish to create revocable dynasty trusts, the trust provisions could provide that, upon the grantor’s death, the trust will automatically convert to an irrevocable trust for the benefit of the Wealth Creator’s descendants.

In accordance with IRC§§ 671 to 679, trusts are classified either as “Grantor Trusts” or “Non-Grantor Trusts” for U.S. income tax purposes. Generally, revocable trusts are grantor trusts for U.S. tax purposes and the transfer of the grantor’s assets to a revocable trust is not considered a “completed gift” for U.S. tax purposes. Since assets in the trust can be retrieved by the grantor at any given time, the assets are still considered owned by the grantor for most legal purposes and income tax purposes. When the grantor deceases, the assets held by the revocable trust are generally includible in the grantor’s estate. Thus, transfer taxes (gift taxes, estate taxes and GST) may be levied.

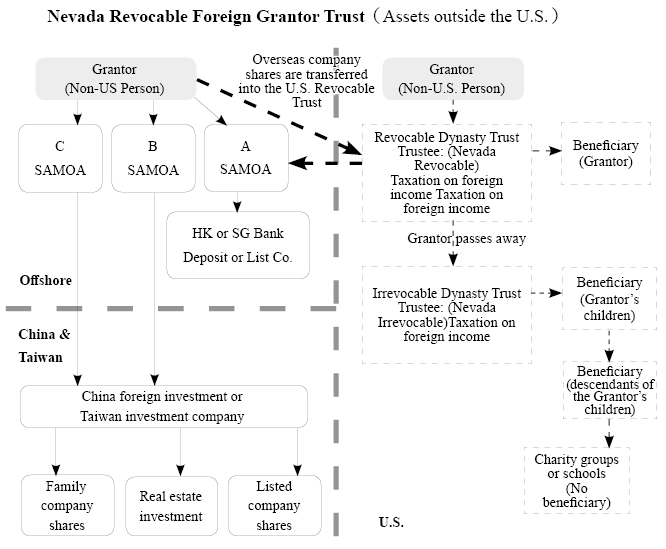

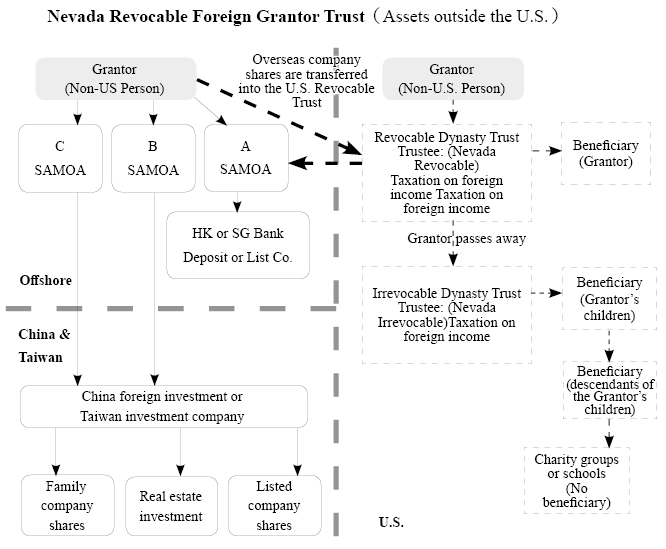

Please see below for an illustrative U.S. revocable trust structure:

Whether the assets held by the trust are subject to income tax and / or transfer taxes generally depend on a number of factors, including the nationality of the grantor and the source of the income generated.

(1) A Non-U.S. person settles a U.S. Revocable Dynasty Trust

Prior to settling a U.S. trust, a non-U.S. person should consider ① whether the assets he wishes to place in the trust are U.S.-based assets (or generate income effectively connected to the U.S.) and ②whether the beneficiaries (current and future) are U.S. persons or non-U.S. persons.

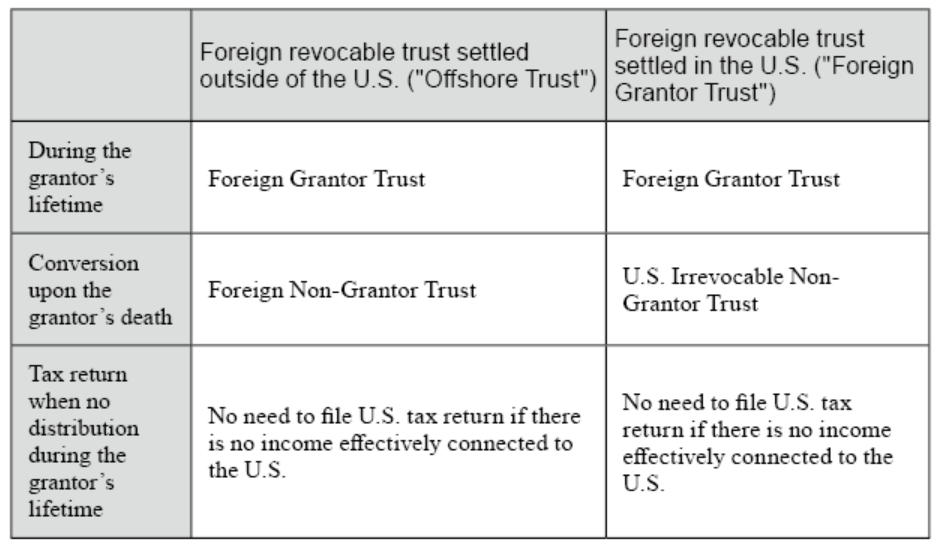

When settling a revocable trust, the trust provisions are most likely drafted so that the trust maintains a grantor trust status, which allow the income of the trust to be taxed to the grantor rather than the trust itself. If the grantor is a non-U.S. person and the trust fails the control test (described previously, essentially having a non-U.S. company or individual serve as the Trust Protector), he or she will have settled a foreign grantor trust. Once the grantor passes away, the foreign grantor trust automatically converts to a foreign non-grantor trust. At this point, if the beneficiaries of the trust are U.S. persons, throwback tax rules may apply to the income generated by the trust. Generally, throwback tax rules only apply when the trust is a foreign trust and when current year distributions exceed current year income. When this happens, income earned in the past is distributed from the trust and taxed at generally heavy rates. Thus, it is preferred that the foreign non-grantor trust be converted to a U.S. non-grantor trust to prevent throwback tax rules from applying.

Another important aspect to consider is whether the assets and income are “U.S. based.” As described above, when the grantor is a non-U.S. person and the trust fails the control test, the trust becomes a foreign grantor trust. Thus, income generated from the trust are not taxed at the trust level but rather taxable to the grantor. As a foreigner, for U.S. federal income tax purposes, the grantor is only taxed on income effectively connected to the U.S. As such, assets placed in these trust consist primarily of foreign assets, which do not trigger U.S. tax consequences so long as the grantor is alive. Further, if the assets placed in the trust are not U.S.-situs assets for estate tax purposes (please refer to Appendices, Section A), the assets held in the trust would not be subject to U.S. estate taxes upon the grantor’s death. Once the grantor deceases, the trust would become irrevocable and thus subject to U.S. income tax.

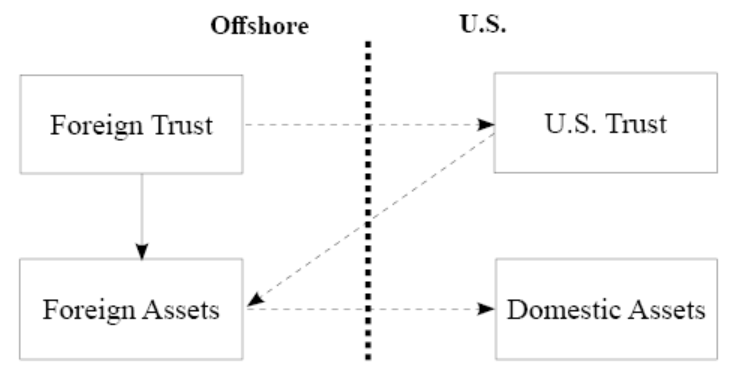

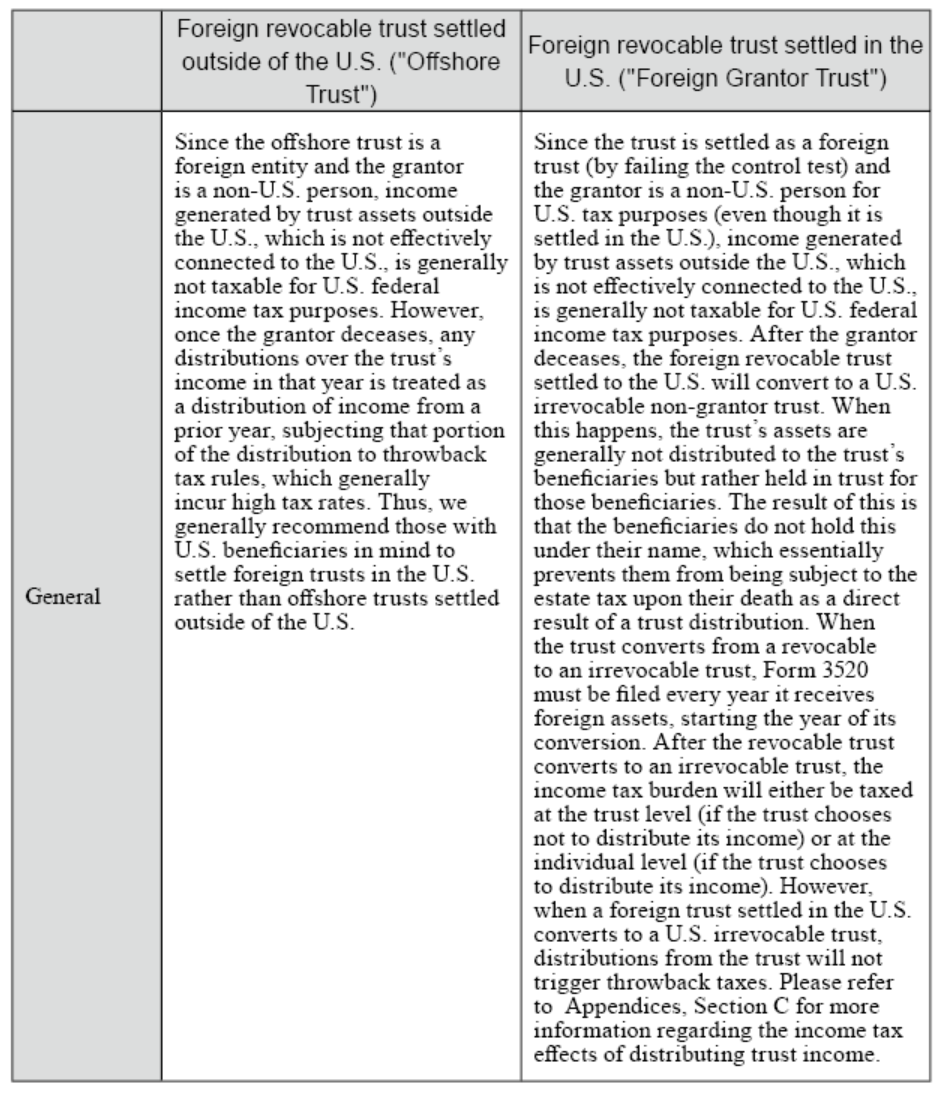

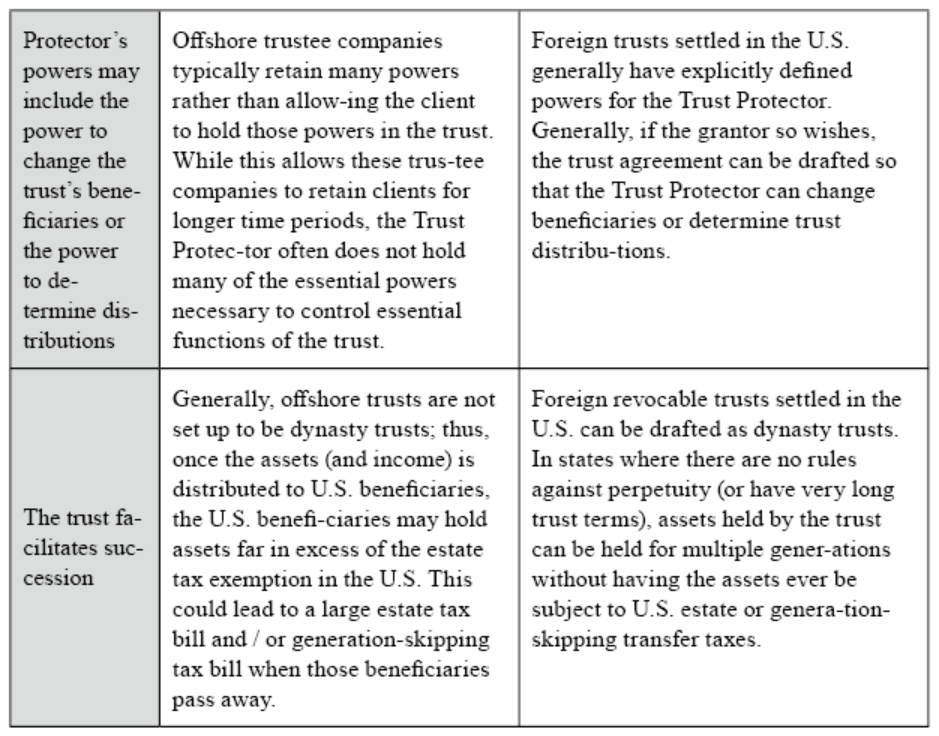

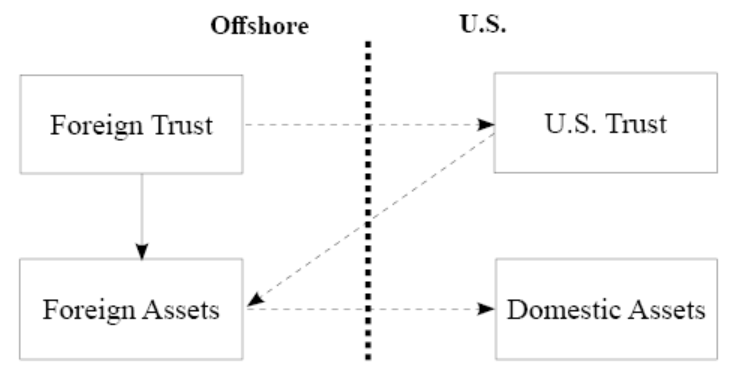

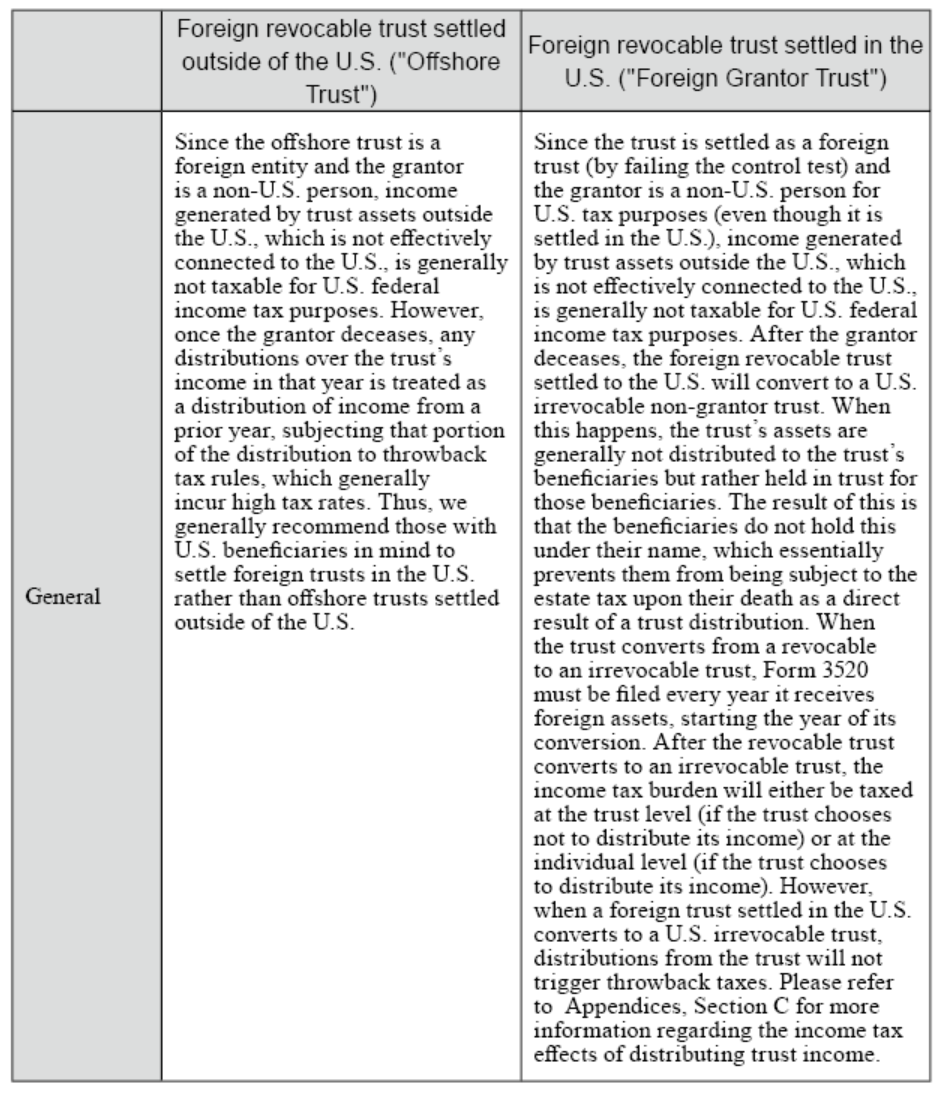

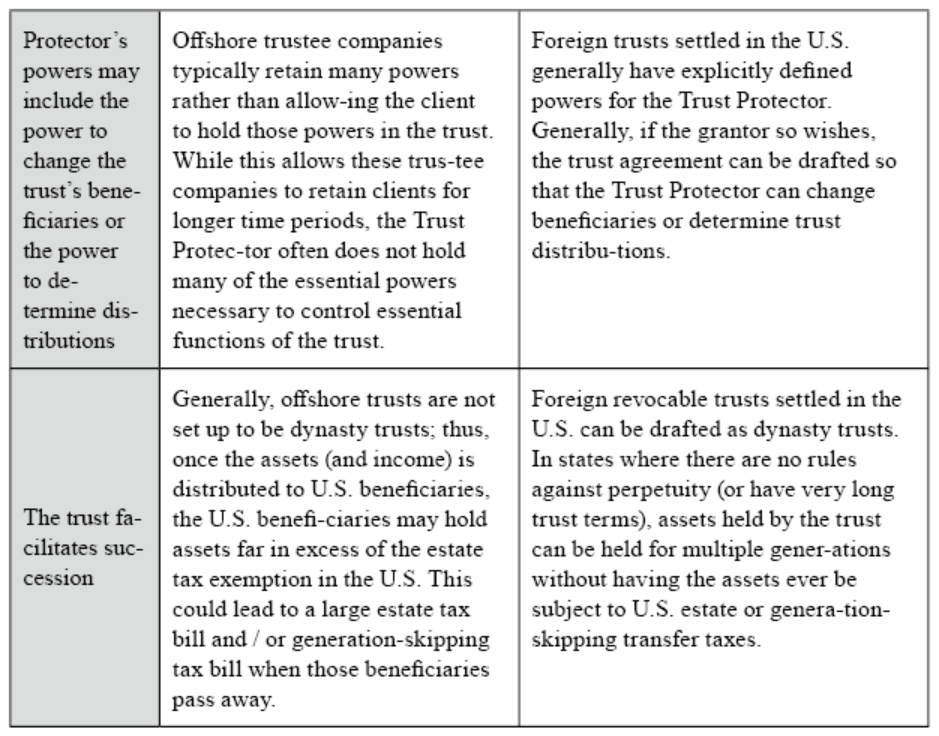

If beneficiaries are U.S. persons for income tax purposes and the grantor holds primarily assets generating income outside of the U.S., a U.S. revocable trust structured as a foreign grantor trust may be suitable. The primary benefits are that ① U.S. income tax is deferred until the grantor deceases and② U.S. beneficiaries will not be subject to throwback tax rules if they receive distributions greater than the trust’s income in a particular year.Please see below for a detailed comparison between foreign trusts settled in the U.S. and offshore trusts:

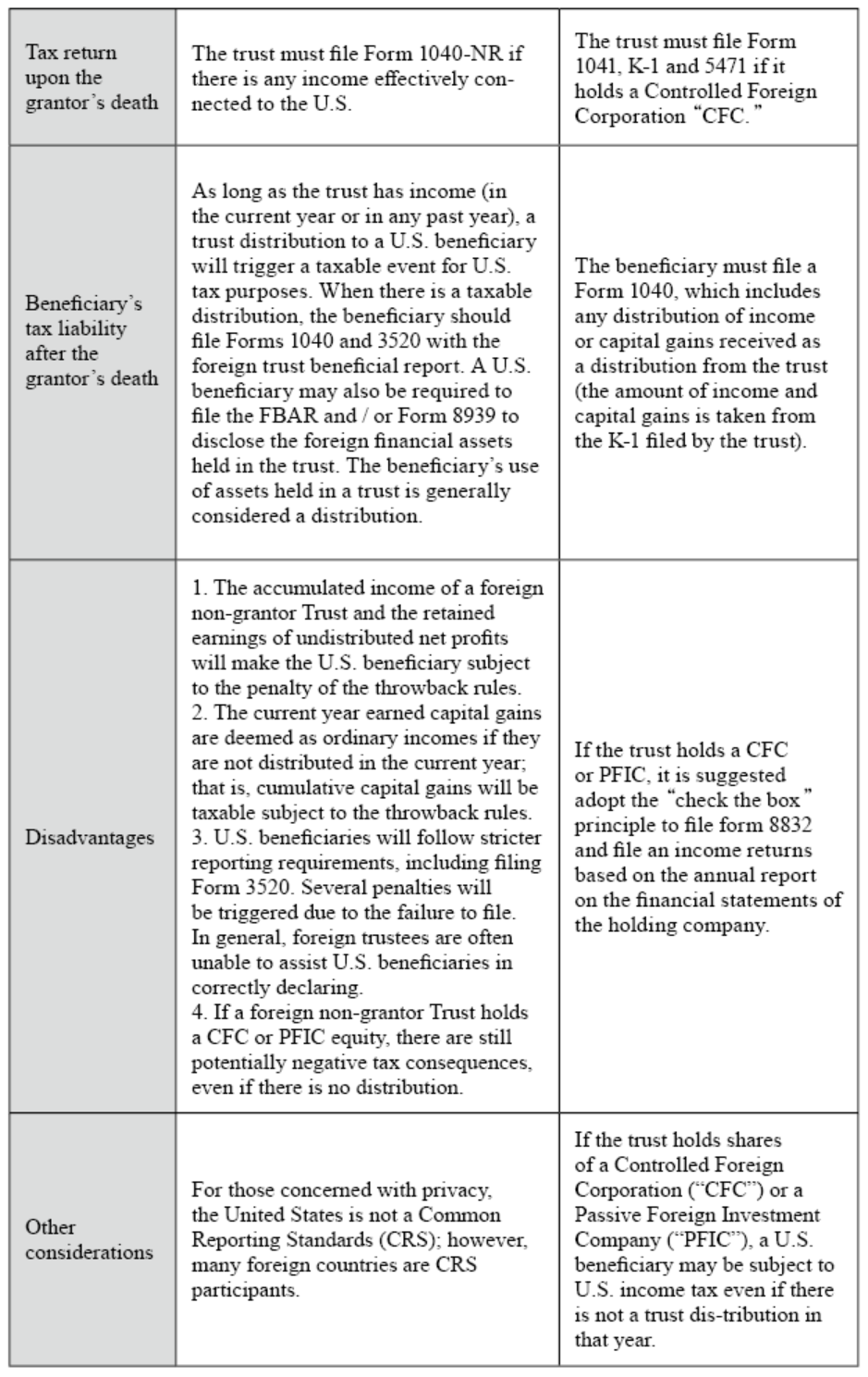

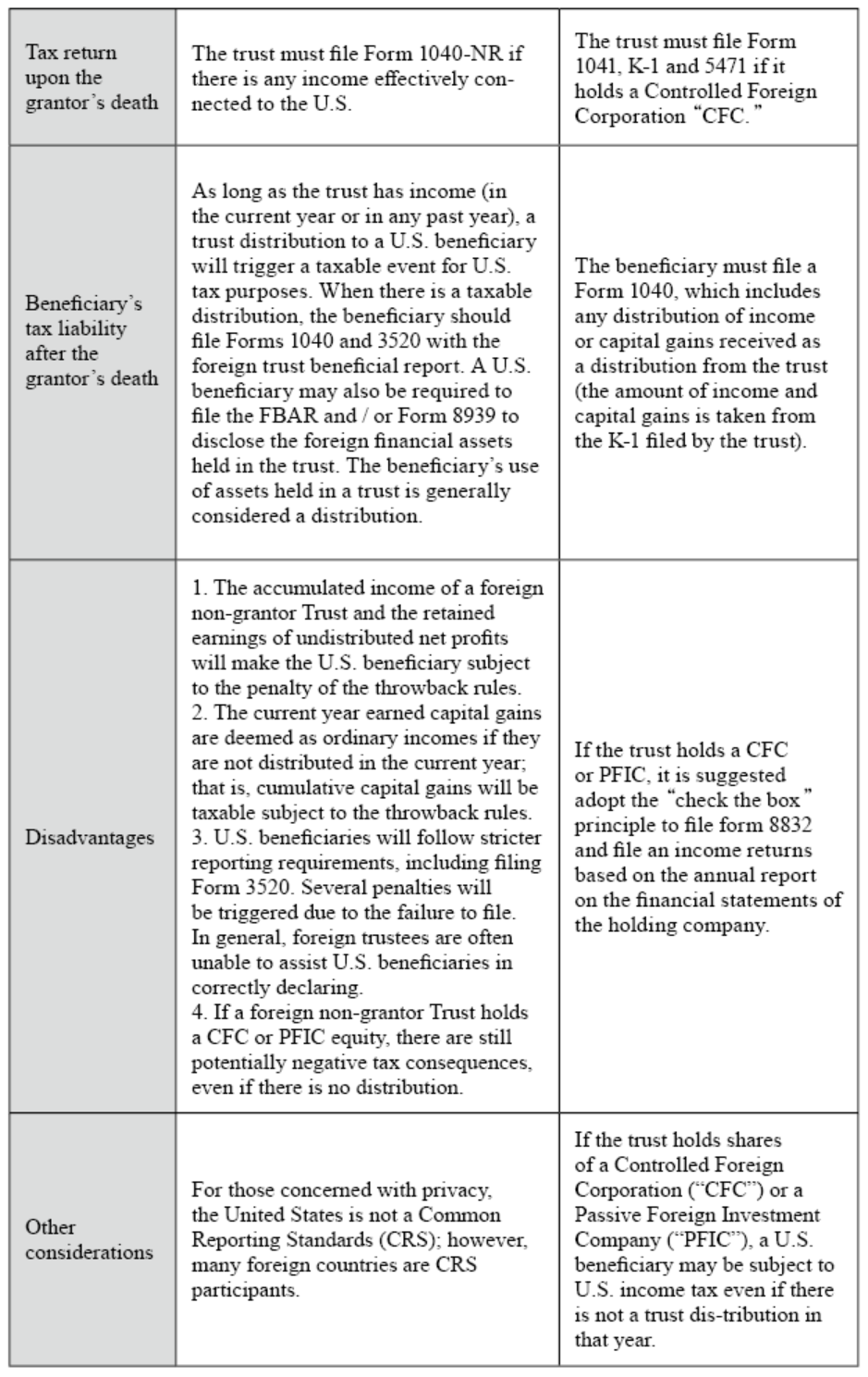

If a trust is established by a non-U.S. person (non-U.S. tax resident) and its beneficiary is a U.S. person, the comparison of the U.S. taxation on the Trust income is as follows:

(2) Non-U.S. person settles a Revocable Dynasty Trust in the U.S. and gifts foreign assets to the trust

When a U.S. revocable grantor trust holds foreign assets, income generated from trust assets are still attributed to the grantor for U.S. income tax purposes. As long as there is no income effectively connected to the U.S., income generated by trust assets would not be subject to U.S. income tax. Since U.S. person beneficiaries are not liable for income tax when receiving distributions prior to the grantor’s death, they would only be required to file the Form 3520 (section three) to disclose the receipt of assets from a foreigner. When the grantor deceases, as long as the Trust continues to satisfy the court test and the control test, the Trust will become a U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust. Since the trust assets are foreign, no transfer taxes will be due upon the conversion. Once the trust converts into a U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust, both domestic and foreign assets will begin to be subject to U.S. income tax. Further, the trust is also then required to disclose information regarding its foreign assets in accordance with the Internal Revenue Code.

Non-U.S. persons who settle revocable dynasty trusts with the plan of using the trust to hold foreign assets usually consider the following:

I. Since the trust is revocable, it can be revoked by the grantor at any time. If revoked, the assets are transferred back to the grantor.

According to IRC§§671-678, as long as the grantor owns significant power over the decision on the trust asset, or the income generated from the trust assets can only be owned by the grantor, the trust is a grantor trust as defined in U.S. trust Law. This kind of trust is definitely a grantor trust due to the grantor’s ability to revoke the trust. With a grantor trust, the grantor can control the trust assets and revoke the trust to retrieve the assets without any restrictions.

II. A revocable dynasty trust protects property so that the property will not be claimed by others other than the beneficiaries.

As a revocable trust, the trust will be classified as a grantor trust for U.S. income tax purposes under IRC§§671-678. Since the trust is revocable, the asset protection function of the trust is not as strong as in the case of an irrevocable trust. Creditors of the grantor may still claim those assets as the grantors assets. On the other hand, in most instances, the legal owner of the assets has shifted from the grantor to the revocable trust; thus, other countries could view these assets as being owned by the trust and not the grantor himself.

III. Before the grantor deceases, the obligation to report the trust’s income and assets to the U.S. is limited.

Even though the trust may not be subject to U.S. taxation, the trust may still be obligated to file the FBAR form.

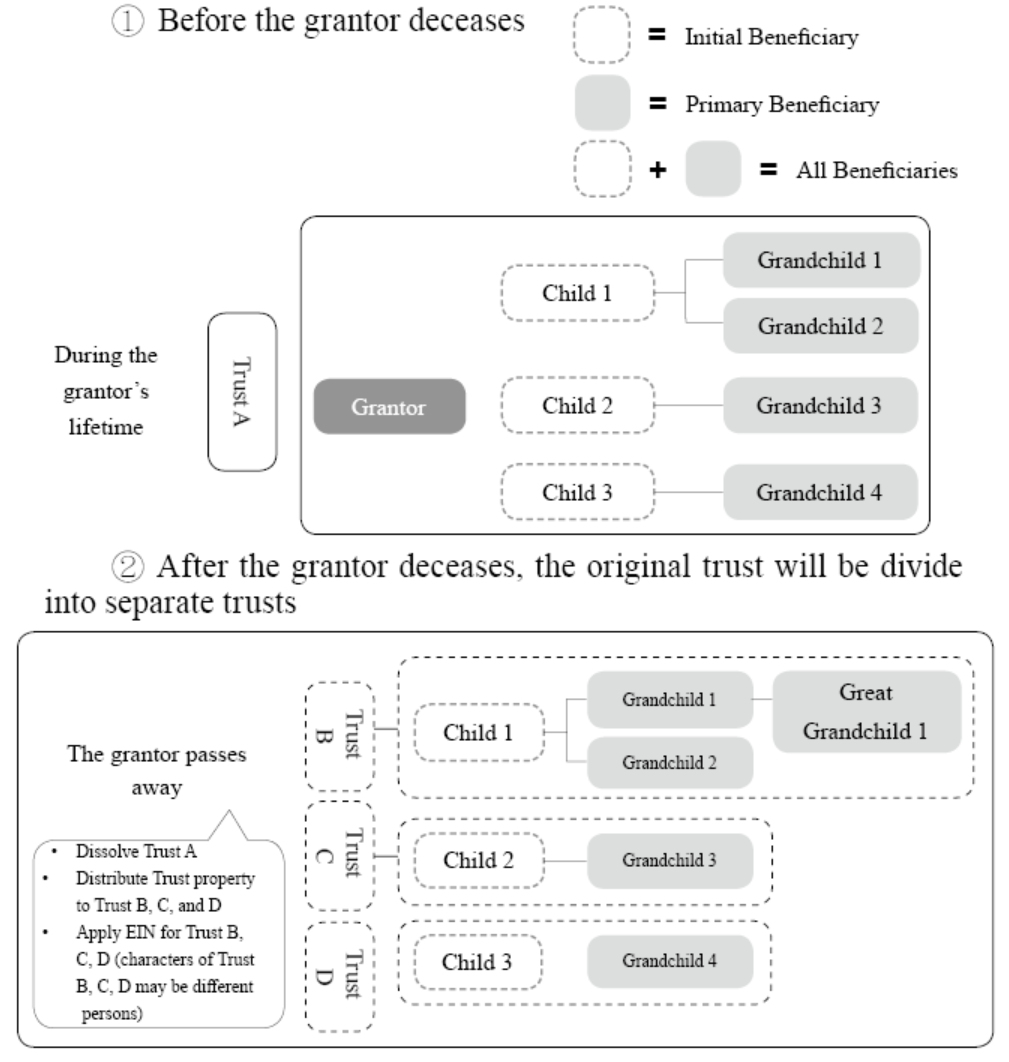

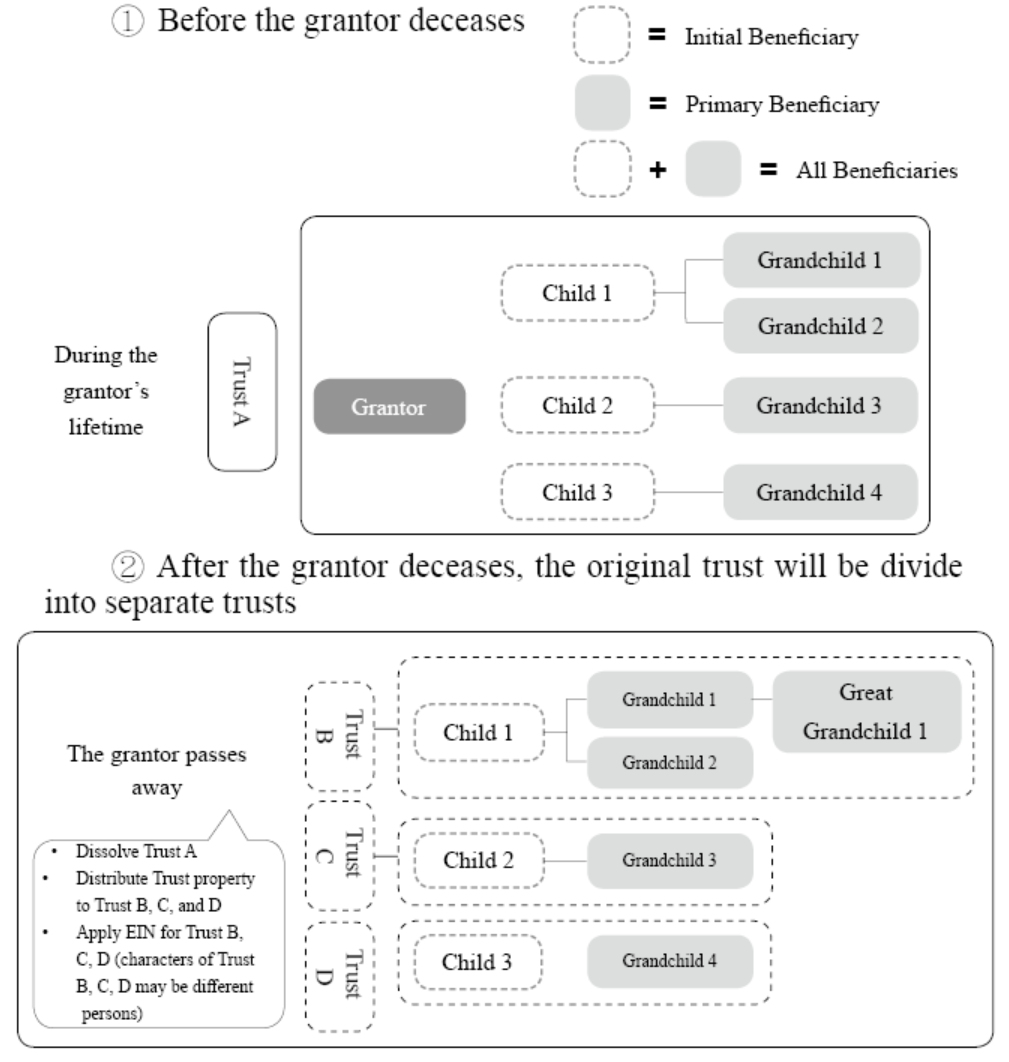

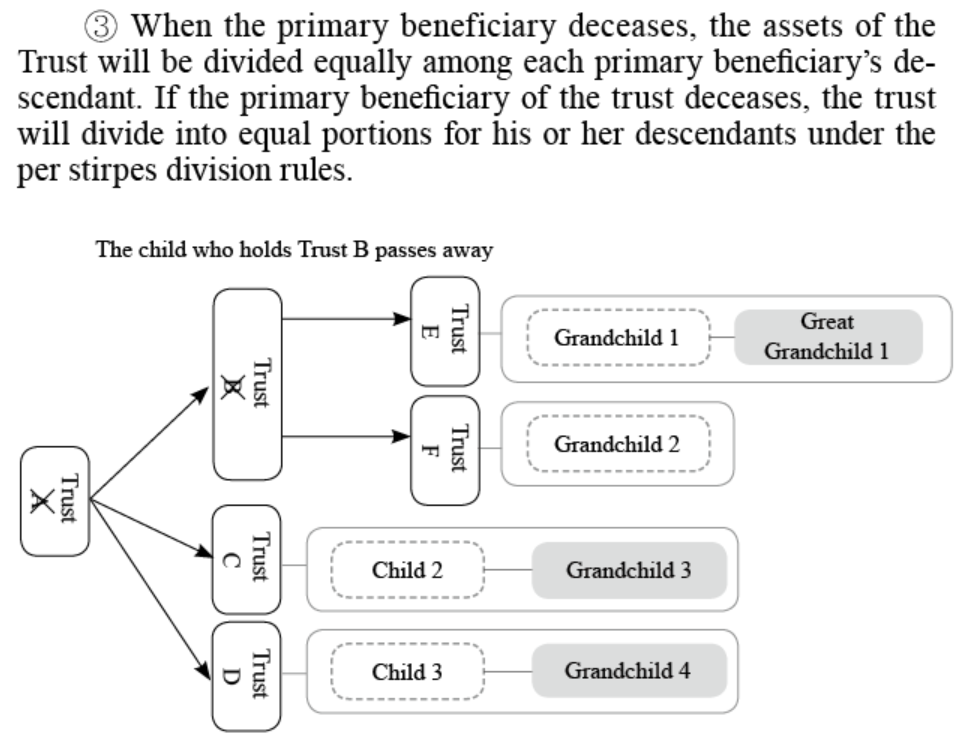

IV. The trust will convert into an irrevocable trust after the grantor deceases and you could apply “check the box” to step up in basis of assets in the Trust.(please refer to appendix C) Otherwise, separate trusts can be established for each beneficiary through decanting or division. Accordingly, it can achieve the goal of wealth succession from one generation to the next without incurring any estate tax, gift tax or GST. The trust agreement may specify that the trust be divided per stirpes:

As previously described, when the grantor deceases, the trust will convert into a U.S. irrevocable trust if it continues to satisfy both the court test and control test. Since the grantor is a foreigner and the trust assets gifted are as non-U.S. situs assets for U.S. estate tax purposes, there is no U.S. transfer tax. After the trust becomes a U.S. irrevocable trust, the trust can be divided into separate trusts for each beneficiary The trust would also protect protection from the beneficiaries’ creditors (including in the event of divorce) both during the grantor’s lifetime and after the grantor’s death.

(3) The main content of trust agreement for the U.S. revocable dynasty trust.

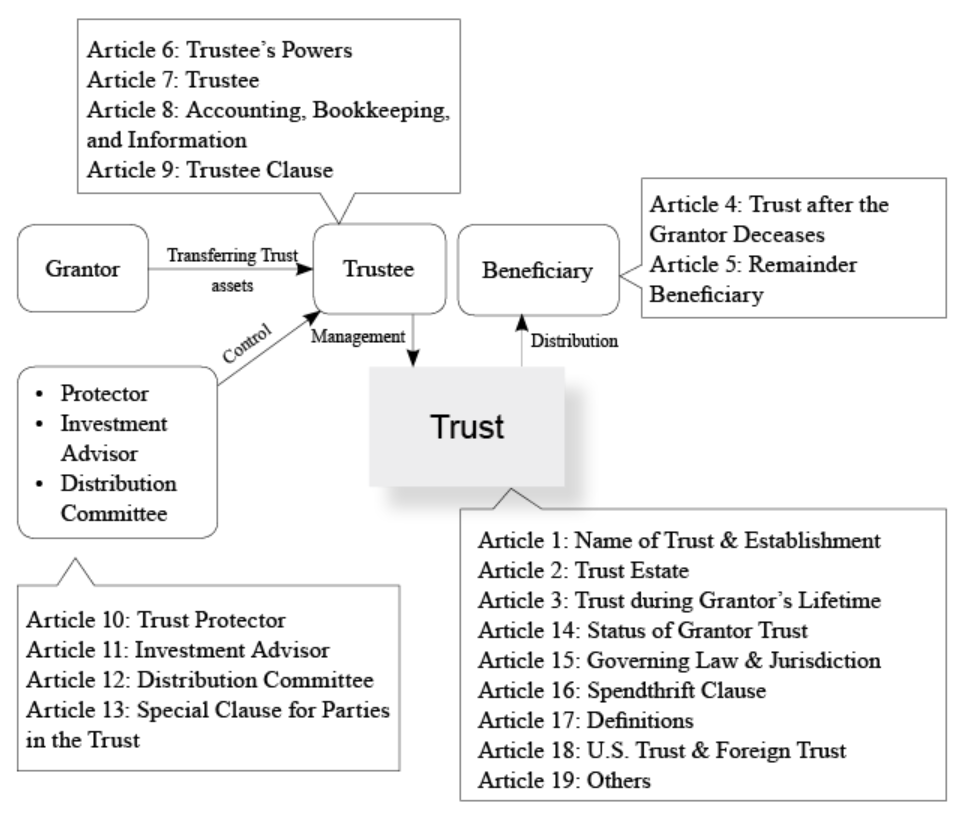

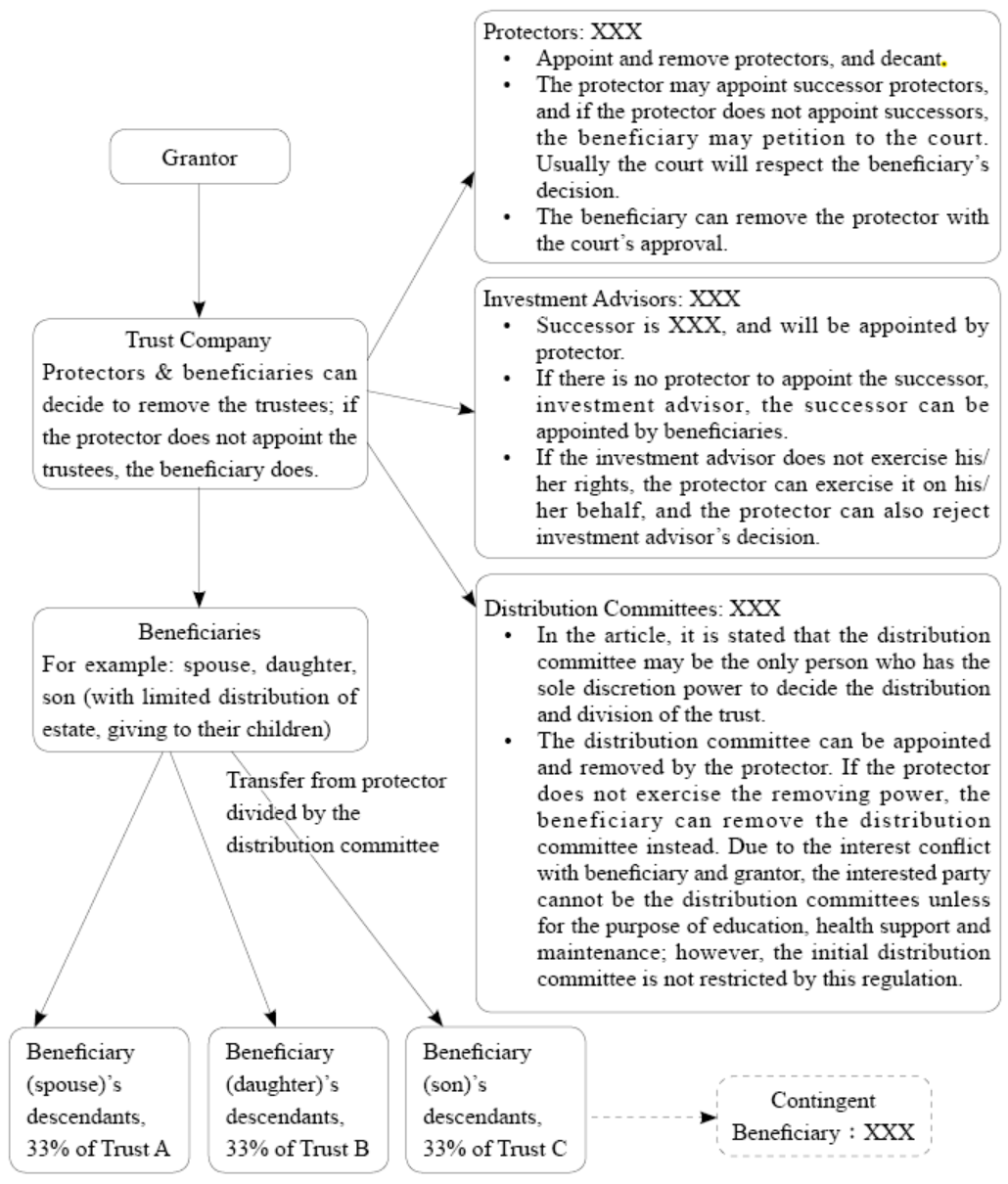

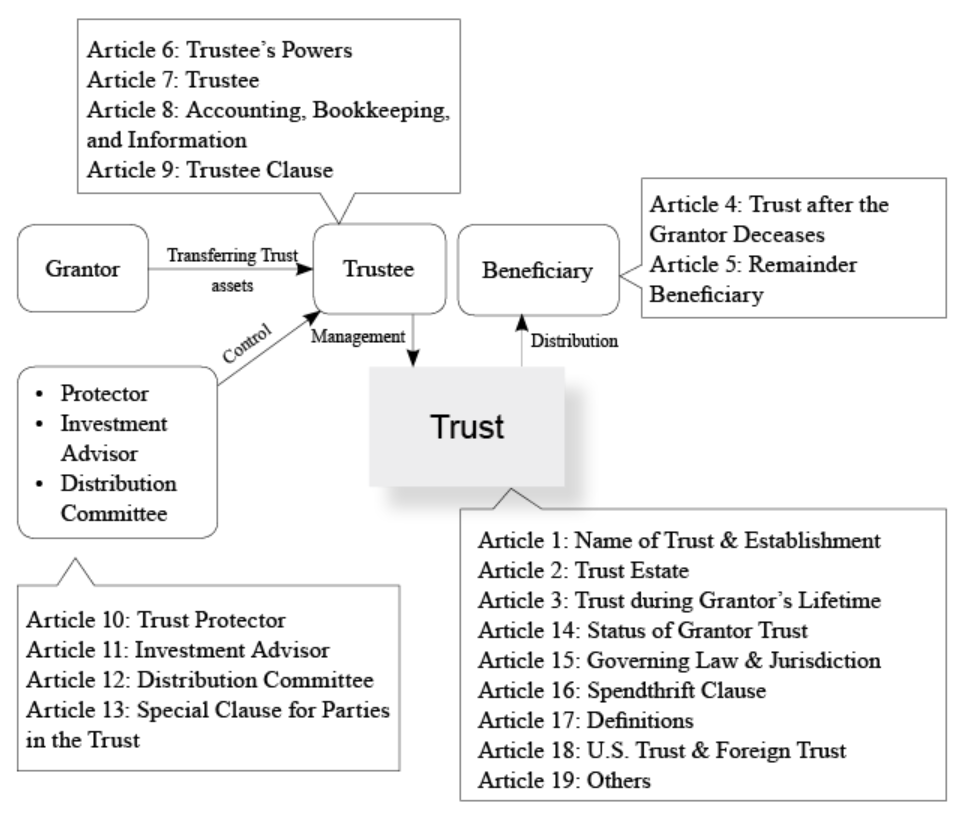

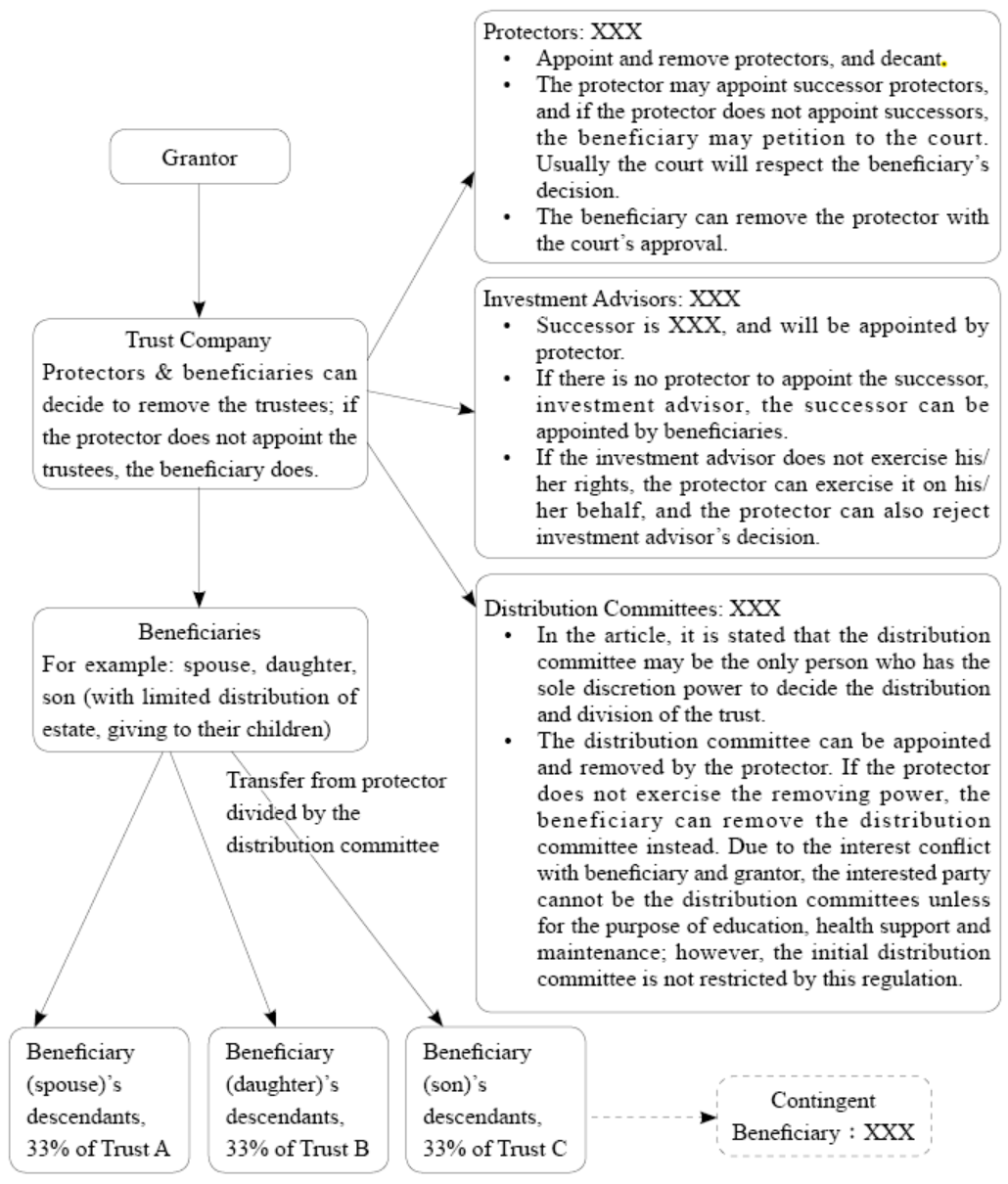

The illustrative structure below briefly introduces the trust agreement and the various roles defined in the trust agreement:

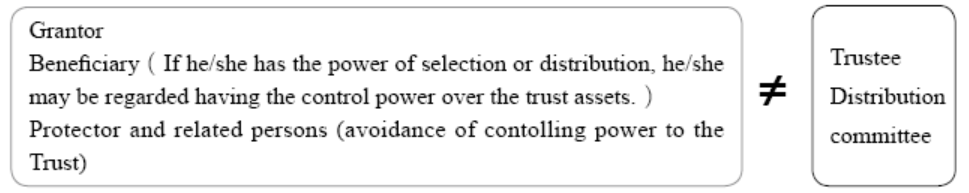

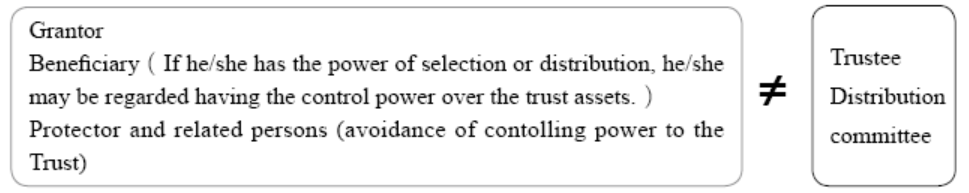

Most trust agreements are drafted so that each power holder (each of the roles) is independent of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. The main purpose of this independence is to separate the trust assets from the assets of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. By doing so, the structure minimizes the risk of incurring both income taxes and transfer taxes. Primarily, trust attorneys look at the following when determining independence (though other rules may apply for specific situations):

I. The trust should not allow the grantor or any beneficiary from attaining too much power. This could affect the trust from both an income tax perspective and an estate tax perspective..

II. If the Trust Protector or Distribution Advisor is related to the grantor or any beneficiary, the trust agreement should disallow these power holders from distributing trust assets to themselves or persons they are related to. If the trust agreement does not disallow these distributions and a distribution as described above is made, the power holders may be deemed to have control over the trust, leading to adverse tax consequences.

If the beneficiary has the power to appoint the trustee, protector, investment direction advisor or the distribution advisor or committee, the trust agreement typically limits his or her ability to assign related parties to those roles. In the example below, a trust agreement specifies the assignment powers given to the beneficiaries of the trust:

I. Trustee: The trustee may be appointed by the trust protector. If the protector is unable to exercise his power of assignment, the related parties (typically beneficiaries) can apply to have one appointed by a competent court in the trust’s jurisdiction.

II. Trust Protector:

During the grantor’s lifetime:

III. Investment direction advisor: The initial investment direction advisor can appoint a successor investment direction advisor. If the initial investment advisor appoint his or her successor, the trust protector can appoint his successor. The protector can also appoint himself or a beneficiary as investment direction advisor.

IV. Distribution Committee: Typically, the distribution committee or distribution advisor is assigned by the trust protector.

The following diagram summarizes the concepts regarding related parties:

Each role holds an important power within the trusts:

In addition, when the initial trust protector passes away, the main beneficiary becomes the new trust protector. The trust protector has the right to appoint and remove those serving in the following capacities: (i) the investment direction advisor, (ii) the distribution advisor and (iii) the trustee. Trust agreements typically limit the powers assigned to the trust’s beneficiaries to prevent the trust assets from being includible in the beneficiaries’ estate. Based on the Code of Federal Regulation (C.F.R), the successor of the protector cannot be the related to the beneficiary as listed: a spouse, parent, lineal blood relative, sibling, employee or employee of the trust.

3. Foreign Trust settled in the U.S.

For U.S. tax purposes, a trust is considered as a U.S. domestic trust or a foreign trust in accordance with the court test and the control test. If a trust satisfy both the court test and the control test, the trust will be considered a U.S. domestic trust. If the trust fails either the court test or the control test, it will be considered a foreign trust. To learn more about court test and control test, please refer to Appendices, Section D.

The trust and its grantor are not obligated to pay U.S. income tax or file a U.S. Federal income tax return if:

IV. Moving Offshore Trusts into the U.S.

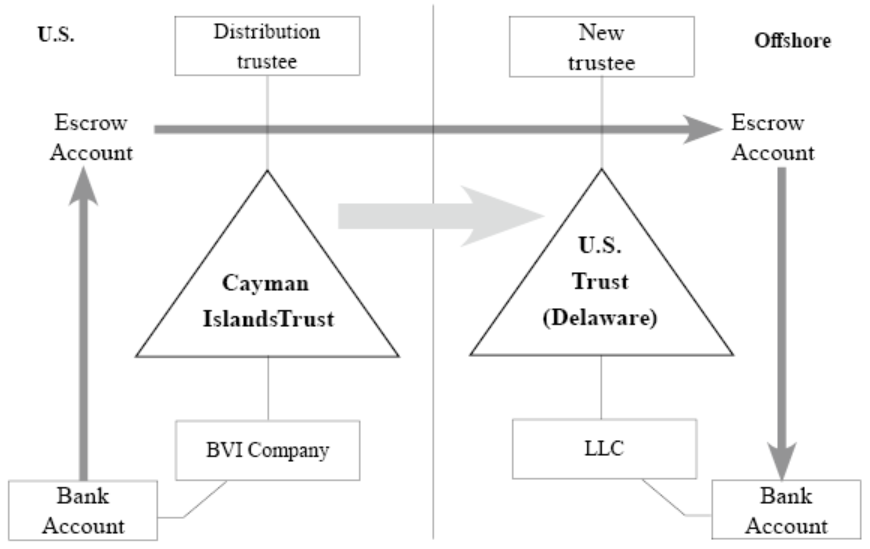

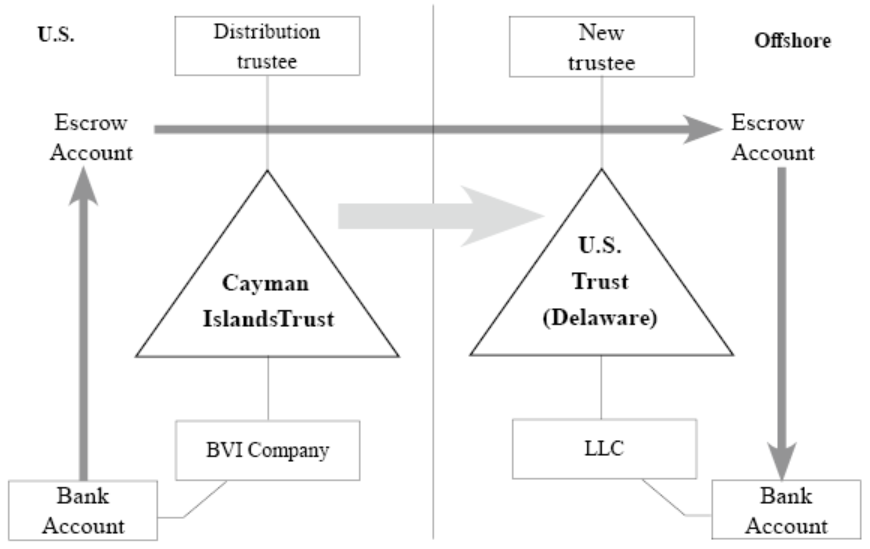

If the original trust agreement allows, the trustee can decant the trust’s assets to a new trust for the same beneficiaries. The terms of the new trust agreement could be drafted to suit the needs of the various power holders or the trust’s beneficiaries. While the transfer of trust assets may give the existing trust flexibility, it could also obligate the trust or its beneficiaries to pay additional taxes. As such, the trustee is often careful when considering a decanting, especially if it is from one jurisdiction to another.

II. State trust law

Evaluate whether the new trust jurisdiction (the U.S., in this case) is superior to the original trust jurisdiction (the Cayman Islands, in this case). If so, notify both the trustee of the original trust and the trustee of the new trust and request that they process the decanting. The grantor should transfer funds from a company’s bank account (held under the original trust) to the original trust’s escrow account. Then, the grantor should notify the original trustees to transfer those funds to the new trust’s escrow account. After entering the new trust’s escrow account, the funds can then be sent to the bank account of the company held by the new trust.

(3) Preparation of information required by the original trustee

II. Provide background information of the new trustee

III. Providing information regarding the controlling persons of the new trustee

IV. Attorneys operating in the new trust’s jurisdiction draft a new trust agreement; the new trust agreement must indemnify the original trustee to allow for a smooth decanting.

V. A letter drafted for the original trustee explaining the reasons for the creation of a new trust and the transfer of assets to the new trust. Generally, this letter explains that the transfer is in the best interest of the trust’s beneficiaries and that the decanting would not trigger adverse tax consequences for the trust’s beneficiaries.

(4) Preparation of information required for the new trustees

An irrevocable trust is a trust that the grantor cannot revoke, upon settling the trust. The grantor, having irrevocably transferred ownership of his or her assets into the trust, is no longer the legal owner of the property transferred. Usually, a trust agreement is so structured so that assets transferred to an irrevocable trust are not includible in the grantor’s estate.

If the beneficiary (or beneficiaries) is a U.S. person(s) and the Wealth Creator intends permanently transfer his or her assets into the U.S., a U.S. irrevocable trust may be an effective tool. Once transferred to the U.S. trust, the trust agreement would usually indicate that the U.S. (and the state in which the trust is settled) is the governing jurisdiction. Hence, assets placed in a U.S. trust is generally protected by U.S. laws. First, you must understand that if the assets are producing income in the U.S., income tax consequences are generally the same whether the trust be revocable or irrevocable. Where a trust is properly structured, tax consequences are lighter for non-U.S. persons, when compared to their U.S. counterparts. However, if a foreign grantor places U.S. situs assets for estate tax purposes in a revocable trust, his or her descendants may be subject to high U.S. estate taxes. This is especially given the fact that non-U.S. persons generally have a significantly lower estate tax exemption threshold than U.S. persons.

As a mainstay for many wealthy families in the U.S., Delaware has promoted itself as being one of the most “trust friendly” states. In 1986, Delaware abolished its rule against perpetuities in its entirety, allowing Delaware trusts to retain, invest and reinvest assets and income in perpetuity. Also, while a grantor is unable to revoke an irrevocable trust, the trust’s assets may be “decanted” into another trust. Despite limitations, decanting can often be used as a tool to amend the trust. In addition, the trustee of an irrevocable trust can apply to the Delaware Chancery Court to modify its clauses to meet the needs of the beneficiaries.5

Please see below for an illustrative Delaware irrevocable trust structure:

5 Top Ten Reasons to have your Trust Administered in Delaware

https://library.wilmingtontrust.com/wealth-planning/top-ten-reasons-to-have-your-trust-administered-in-delaware

The above trust is settled by a non-U.S. person in Delaware. A local corporate trustee company is selected to be the trust’s trustee. The trust’s beneficiaries, designated by the grantor, are all U.S. persons. The trust invests in numerous LLCs or LPs, which in turn owns U.S. stocks, bank deposits and real estate.

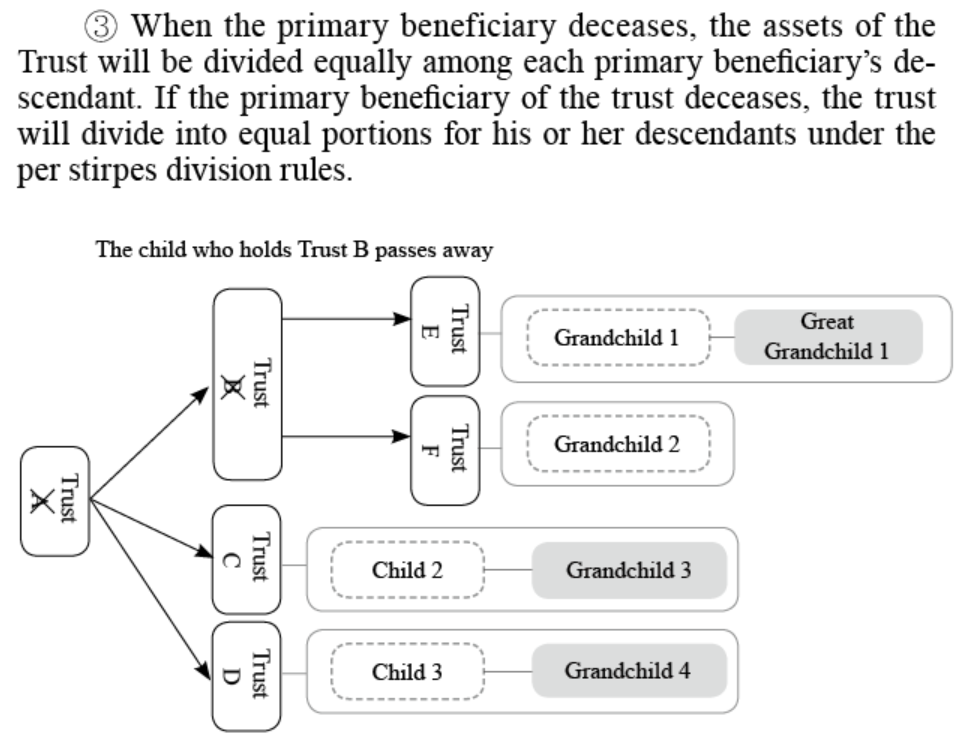

Many families that settle irrevocable trusts incorporate the concept of “per stirpes.” Generally, this means that each descendant of the grantor receives an equal amount of trust assets if the trust were to be divided in the future. The descendants of each of the grantor’s descendants would also receive an equal share of the trust’s assets left to them by their parents.

Generally, under this structure, if a beneficiary passes away with descendants, the beneficiary’s descendants would receive an equal share of that beneficiary’s share of the trust’s assets. If the beneficiary does not have descendants upon his or her death, the trust’s assets apportioned to that beneficiary would then be distributed among the beneficiaries’ siblings (or their descendants), per stirpes. Lastly, if the deceased beneficiary has no descendants or siblings upon his or her death, the assets apportioned to the deceased beneficiary would then be distributed among the deceased beneficiaries’ parents’ siblings (and their descendants), per stirpes, assuming that the deceased beneficiaries’ parents have already passed away.

The following generally indicates whether a U.S. irrevocable trust would be suitable for the Wealth Creator.

(1) The Grantor (generally, the Wealth Creator) does not have the intention of immigrating to the U.S.

If structured correctly, a transfer of assets to a U.S. irrevocable trust can be deemed a completed gift for U.S. tax purposes. If a non-U.S. person transfers non-U.S. situs assets for gift tax purposes into a U.S. irrevocable trust, there is U.S. gift taxes will generally not be owed by the grantor. Generally, the Trustee will file a 3520 Form in the calendar year after the year the gift was consummated to disclose that the trust has received assets from a non-U.S. person.

However, if the grantor is a U.S. person, then the gift of assets would trigger U.S. gift taxes if the gift exceeds the individual’s lifetime gift and estate tax exemption, subject to certain conditions, disregarding whether the assets are U.S. or non-U.S. situs for gift tax purposes.

(2) When foreign assets enter the U.S., the future assets can be used for investment, receiving fructus and distributing income in the U.S. for a long period of time.

The foreign assets will receive asset protection after it has entered the U.S. irrevocable trust for a specific number of years. The year limit of asset protection differs in every state. In Nevada, the assets will receive protection after it has entered the trust for two years. For example, the trust assets can be protected from the claim of creditor, claim of distribution of Marital Property or lawsuit and thus when the future principle of the trust distributes to the beneficiaries, it will not result in transfer taxes such as estate or gift taxes. The fructus or principle accumulated under trust assets will be subject to income tax under the U.S. tax laws.

(3) Gifting assets to an irrevocable trust could prevent inheritance disputes.

Once the irrevocable trust is established, the management of assets held by the trust should follow instructions set forth by the trust agreement. Trust agreements must be drafted (or at least reviewed) by an attorney licensed to practice law in the state the trust is settled. Since the settling of the trust requires a notary and witnesses, it is unlikely that the trust is subject to disputes regarding the legitimacy of the trust. When compared to most wills, a trust agreement is more thorough and is generally more capable of withstanding legal scrutiny.

(4) Transfer taxes including estate, gift and generation-skipping taxes, are minimized or eliminated altogether if the grantor is a non-U.S. person.

U.S. individuals are usually subject to estate taxes, gift taxes and / or generation-skipping taxes (GST) upon the transfer of substantial assets from one generation to the next. Generally, “substantial assets” is defined by the estate and gift tax exemption (and the GST exemption) at the time of the transfer. For non-U.S. persons, a properly structured dynasty trust may prevent assets held by the trust from ever facing U.S. transfer taxes.

To avoid the double taxation during the assets transfer, the family could pass on the assets to the next generation by means of “division” and “decanting” within the irrevocable trust. (Please refer to the next page.)

(5) Gifting assets to an irrevocable trust could prevent creditors (including spouses, in cases of a marriage dissolution) of the trust’s grantor or beneficiaries from claiming the trust assets.

Once assets are transferred to an irrevocable trust, the trust then becomes the owner of those assets from that point onwards. Among the myriad of reasons to settle an irrevocable trust, asset protection is one of the most important considerations for many Wealth Creators. When properly drafted and operated legitimately, the trust agreement and the trust’s jurisdiction can pose considerable difficulties for any potential creditors.

2. U.S. Revocable Trusts

Generally, revocable trusts are drafted so that the grantor is able to revoke the trust or amend the trust’s provisions at his or her discretion without any third party consent. After transferring assets into revocable trust, the grantor can generally distribute any principal and / or income to the trust’s beneficiaries or to himself without triggering any transfer tax consequences. For Wealth Creators who wish to create revocable dynasty trusts, the trust provisions could provide that, upon the grantor’s death, the trust will automatically convert to an irrevocable trust for the benefit of the Wealth Creator’s descendants.

In accordance with IRC§§ 671 to 679, trusts are classified either as “Grantor Trusts” or “Non-Grantor Trusts” for U.S. income tax purposes. Generally, revocable trusts are grantor trusts for U.S. tax purposes and the transfer of the grantor’s assets to a revocable trust is not considered a “completed gift” for U.S. tax purposes. Since assets in the trust can be retrieved by the grantor at any given time, the assets are still considered owned by the grantor for most legal purposes and income tax purposes. When the grantor deceases, the assets held by the revocable trust are generally includible in the grantor’s estate. Thus, transfer taxes (gift taxes, estate taxes and GST) may be levied.

Please see below for an illustrative U.S. revocable trust structure:

Whether the assets held by the trust are subject to income tax and / or transfer taxes generally depend on a number of factors, including the nationality of the grantor and the source of the income generated.

(1) A Non-U.S. person settles a U.S. Revocable Dynasty Trust

Prior to settling a U.S. trust, a non-U.S. person should consider ① whether the assets he wishes to place in the trust are U.S.-based assets (or generate income effectively connected to the U.S.) and ②whether the beneficiaries (current and future) are U.S. persons or non-U.S. persons.

When settling a revocable trust, the trust provisions are most likely drafted so that the trust maintains a grantor trust status, which allow the income of the trust to be taxed to the grantor rather than the trust itself. If the grantor is a non-U.S. person and the trust fails the control test (described previously, essentially having a non-U.S. company or individual serve as the Trust Protector), he or she will have settled a foreign grantor trust. Once the grantor passes away, the foreign grantor trust automatically converts to a foreign non-grantor trust. At this point, if the beneficiaries of the trust are U.S. persons, throwback tax rules may apply to the income generated by the trust. Generally, throwback tax rules only apply when the trust is a foreign trust and when current year distributions exceed current year income. When this happens, income earned in the past is distributed from the trust and taxed at generally heavy rates. Thus, it is preferred that the foreign non-grantor trust be converted to a U.S. non-grantor trust to prevent throwback tax rules from applying.

Another important aspect to consider is whether the assets and income are “U.S. based.” As described above, when the grantor is a non-U.S. person and the trust fails the control test, the trust becomes a foreign grantor trust. Thus, income generated from the trust are not taxed at the trust level but rather taxable to the grantor. As a foreigner, for U.S. federal income tax purposes, the grantor is only taxed on income effectively connected to the U.S. As such, assets placed in these trust consist primarily of foreign assets, which do not trigger U.S. tax consequences so long as the grantor is alive. Further, if the assets placed in the trust are not U.S.-situs assets for estate tax purposes (please refer to Appendices, Section A), the assets held in the trust would not be subject to U.S. estate taxes upon the grantor’s death. Once the grantor deceases, the trust would become irrevocable and thus subject to U.S. income tax.

If beneficiaries are U.S. persons for income tax purposes and the grantor holds primarily assets generating income outside of the U.S., a U.S. revocable trust structured as a foreign grantor trust may be suitable. The primary benefits are that ① U.S. income tax is deferred until the grantor deceases and② U.S. beneficiaries will not be subject to throwback tax rules if they receive distributions greater than the trust’s income in a particular year.Please see below for a detailed comparison between foreign trusts settled in the U.S. and offshore trusts:

If a trust is established by a non-U.S. person (non-U.S. tax resident) and its beneficiary is a U.S. person, the comparison of the U.S. taxation on the Trust income is as follows:

(2) Non-U.S. person settles a Revocable Dynasty Trust in the U.S. and gifts foreign assets to the trust

When a U.S. revocable grantor trust holds foreign assets, income generated from trust assets are still attributed to the grantor for U.S. income tax purposes. As long as there is no income effectively connected to the U.S., income generated by trust assets would not be subject to U.S. income tax. Since U.S. person beneficiaries are not liable for income tax when receiving distributions prior to the grantor’s death, they would only be required to file the Form 3520 (section three) to disclose the receipt of assets from a foreigner. When the grantor deceases, as long as the Trust continues to satisfy the court test and the control test, the Trust will become a U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust. Since the trust assets are foreign, no transfer taxes will be due upon the conversion. Once the trust converts into a U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust, both domestic and foreign assets will begin to be subject to U.S. income tax. Further, the trust is also then required to disclose information regarding its foreign assets in accordance with the Internal Revenue Code.

Non-U.S. persons who settle revocable dynasty trusts with the plan of using the trust to hold foreign assets usually consider the following:

I. Since the trust is revocable, it can be revoked by the grantor at any time. If revoked, the assets are transferred back to the grantor.

According to IRC§§671-678, as long as the grantor owns significant power over the decision on the trust asset, or the income generated from the trust assets can only be owned by the grantor, the trust is a grantor trust as defined in U.S. trust Law. This kind of trust is definitely a grantor trust due to the grantor’s ability to revoke the trust. With a grantor trust, the grantor can control the trust assets and revoke the trust to retrieve the assets without any restrictions.

II. A revocable dynasty trust protects property so that the property will not be claimed by others other than the beneficiaries.

As a revocable trust, the trust will be classified as a grantor trust for U.S. income tax purposes under IRC§§671-678. Since the trust is revocable, the asset protection function of the trust is not as strong as in the case of an irrevocable trust. Creditors of the grantor may still claim those assets as the grantors assets. On the other hand, in most instances, the legal owner of the assets has shifted from the grantor to the revocable trust; thus, other countries could view these assets as being owned by the trust and not the grantor himself.

III. Before the grantor deceases, the obligation to report the trust’s income and assets to the U.S. is limited.

Even though the trust may not be subject to U.S. taxation, the trust may still be obligated to file the FBAR form.

IV. The trust will convert into an irrevocable trust after the grantor deceases and you could apply “check the box” to step up in basis of assets in the Trust.(please refer to appendix C) Otherwise, separate trusts can be established for each beneficiary through decanting or division. Accordingly, it can achieve the goal of wealth succession from one generation to the next without incurring any estate tax, gift tax or GST. The trust agreement may specify that the trust be divided per stirpes:

As previously described, when the grantor deceases, the trust will convert into a U.S. irrevocable trust if it continues to satisfy both the court test and control test. Since the grantor is a foreigner and the trust assets gifted are as non-U.S. situs assets for U.S. estate tax purposes, there is no U.S. transfer tax. After the trust becomes a U.S. irrevocable trust, the trust can be divided into separate trusts for each beneficiary The trust would also protect protection from the beneficiaries’ creditors (including in the event of divorce) both during the grantor’s lifetime and after the grantor’s death.

(3) The main content of trust agreement for the U.S. revocable dynasty trust.

The illustrative structure below briefly introduces the trust agreement and the various roles defined in the trust agreement:

Most trust agreements are drafted so that each power holder (each of the roles) is independent of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. The main purpose of this independence is to separate the trust assets from the assets of both the grantor and the beneficiaries. By doing so, the structure minimizes the risk of incurring both income taxes and transfer taxes. Primarily, trust attorneys look at the following when determining independence (though other rules may apply for specific situations):

I. The trust should not allow the grantor or any beneficiary from attaining too much power. This could affect the trust from both an income tax perspective and an estate tax perspective..

II. If the Trust Protector or Distribution Advisor is related to the grantor or any beneficiary, the trust agreement should disallow these power holders from distributing trust assets to themselves or persons they are related to. If the trust agreement does not disallow these distributions and a distribution as described above is made, the power holders may be deemed to have control over the trust, leading to adverse tax consequences.

If the beneficiary has the power to appoint the trustee, protector, investment direction advisor or the distribution advisor or committee, the trust agreement typically limits his or her ability to assign related parties to those roles. In the example below, a trust agreement specifies the assignment powers given to the beneficiaries of the trust:

I. Trustee: The trustee may be appointed by the trust protector. If the protector is unable to exercise his power of assignment, the related parties (typically beneficiaries) can apply to have one appointed by a competent court in the trust’s jurisdiction.

II. Trust Protector:

During the grantor’s lifetime:

a. Appointed by the person designated in trust agreement; or

b. Appointed by the grantor.

After the grantor deceases:

a. Appointed by the person designated in trust agreement (the main beneficiary in the separate trusts); or

b. Appointed by the qualified beneficiaries’ vote.

- Voting order:

- Appointed by the majority of the adult beneficiaries who are competent.

- If there are no adult beneficiaries who are competent, then the protector is appointed by the majority of the custodians of minors.

- If no action is taken within 30 days, then the trustee may petition to have the court assign a trust protector.

III. Investment direction advisor: The initial investment direction advisor can appoint a successor investment direction advisor. If the initial investment advisor appoint his or her successor, the trust protector can appoint his successor. The protector can also appoint himself or a beneficiary as investment direction advisor.

IV. Distribution Committee: Typically, the distribution committee or distribution advisor is assigned by the trust protector.

The following diagram summarizes the concepts regarding related parties:

Each role holds an important power within the trusts:

- The trust protector yields the greatest power, allowing him or her to secure the trust’s assets. Thus, many trust agreements provide that the appointment of the trust protector be made by the qualified beneficiaries.

- The investment direction advisor is not involved in determining distributions from the trust. As such, the beneficiary or a related party of the beneficiary is typically capable of serving in the capacity of investment direction advisor.

- The selection committee only add charitable organizations as beneficiaries. Typically, the trust protector may appoint members of the selection committee.

- The distribution advisor is appointed by the protector directly and has the power to determine trust distributions to beneficiaries.

In addition, when the initial trust protector passes away, the main beneficiary becomes the new trust protector. The trust protector has the right to appoint and remove those serving in the following capacities: (i) the investment direction advisor, (ii) the distribution advisor and (iii) the trustee. Trust agreements typically limit the powers assigned to the trust’s beneficiaries to prevent the trust assets from being includible in the beneficiaries’ estate. Based on the Code of Federal Regulation (C.F.R), the successor of the protector cannot be the related to the beneficiary as listed: a spouse, parent, lineal blood relative, sibling, employee or employee of the trust.

3. Foreign Trust settled in the U.S.

For U.S. tax purposes, a trust is considered as a U.S. domestic trust or a foreign trust in accordance with the court test and the control test. If a trust satisfy both the court test and the control test, the trust will be considered a U.S. domestic trust. If the trust fails either the court test or the control test, it will be considered a foreign trust. To learn more about court test and control test, please refer to Appendices, Section D.

The disclosures are explained as follows:

(1) The U.S. income tax

In accordance with 26 U.S. Code §641(b), income generated by assets held by foreign or offshore trusts established by non-U.S. persons is attributable to the foreign grantor for U.S. tax purposes. Generally, NRAs are subject to U.S. income tax only on ① U.S. source “fixed, determinable , annual, or periodical income,” generally subject to withholding at a 30% rate on a gross basis (with no offsetting deductions), and ② income that is effectively connected with a U.S. trade or business (“effectively connected income”), which is taxed on a net basis at graduated rates. Generally, foreign trusts are settled to hold shares of offshore companies. This allows the trust to not be taxed in the U.S., in accordance with U.S. tax laws. The trust and its grantor are not obligated to pay U.S. income tax or file a U.S. Federal income tax return if:

① the grantor is a non-U.S. person

② the trust is a foreign trust (or offshore trust)

③ the trust’s assets produce no U.S. source income

④ none of the beneficiaries of the trust are U.S. persons

(2) Information disclosure requirement

A foreign trust settled by a non-resident alien can be categorized as a grantor trust or a non-grantor trust. Since the grantor is a non-resident alien, neither the grantor nor the trust is obligated to file Form 926, Form 3520, Form 3520-A, Form 5471, Form 5472, Form 8865, and Form 8938. However, in accordance with FBAR regulations, the owner or legal holder as determined by 31CFR§1010.350(e)(2)(ii), shall be a U.S. person owns, directly or indirectly, more than 50% voting rights or total shares value of a company, a US person owns, directly or indirectly, more than 50% profit or capital benefits of a partnership or a U.S. person owns, directly or indirectly, 50% or more voting rights, equity or total assets value of the other entity (except those mentioned in (e)(2)(iii) to (iv)). Under these conditions, the offshore financial account held by the trust, the BVI company, the Chinese company or the Taiwanese company is obligated to file FBAR. Thus, the U.S. corporate trustee will be asked to disclose any bank accounts held by companies held by the trust. Under the Bank Secrecy Act, a U.S. person who has a financial interest in, signature authority or other authority over one or more bank, securities, or other financial accounts in a foreign country, must file FinCEN Form 114and Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (a.k.a. FBAR), for each calendar year if the accounts exceed $10,000 in aggregate value. The FBAR is due on the year following the tax year on April 15 and it can be extended until October 15. The non-willful failure to file penalties is upwards of $10,000 per account, while the willful failure to file penalties can reach the greater of $100,000 and 50% of the account value. The FBAR is completely independent of the tax return. The federal income tax return is filed to the Internal Revenue Service while FBAR is filed to the U.S. Department of Treasury.IV. Moving Offshore Trusts into the U.S.

If the original trust agreement allows, the trustee can decant the trust’s assets to a new trust for the same beneficiaries. The terms of the new trust agreement could be drafted to suit the needs of the various power holders or the trust’s beneficiaries. While the transfer of trust assets may give the existing trust flexibility, it could also obligate the trust or its beneficiaries to pay additional taxes. As such, the trustee is often careful when considering a decanting, especially if it is from one jurisdiction to another.

(1) Does the original trustee have the power to decant?

I. Trust agreement

(i) If the trust agreement allows for decanting → O

(ii) If the trust agreement does not allow decanting → X

(iii) If the trust agreement is silent on whether the trust assets may be decanted → competent attorneys from that jurisdiction must check the jurisdiction’s laws and determine whether a decanting is permissible

II. State trust law

(i) If the state’s trust law allows a decanting → O

(ii) If the state’s trust law does not allow decanting or if the trust agreement does not allow for decanting→ X

(iii) If the trust agreement is silent on whether the trust assets may be decanted → competent attorneys from that state must check the state’s laws and determine whether a decanting is permissible; they must also determine whether the state’s laws allow for all decanting or only court-approved decanting.

(2) Evaluate new trustee(s) and the jurisdiction of the new trustEvaluate whether the new trust jurisdiction (the U.S., in this case) is superior to the original trust jurisdiction (the Cayman Islands, in this case). If so, notify both the trustee of the original trust and the trustee of the new trust and request that they process the decanting. The grantor should transfer funds from a company’s bank account (held under the original trust) to the original trust’s escrow account. Then, the grantor should notify the original trustees to transfer those funds to the new trust’s escrow account. After entering the new trust’s escrow account, the funds can then be sent to the bank account of the company held by the new trust.

(3) Preparation of information required by the original trustee

I. Provide background information on the new trust

(i) Full names and addresses of the new trustee(s) and the new trust

(ii) The date the new trust was established

(iii) The tax identification number (EIN) of the new trust

II. Provide background information of the new trustee

(i) Name of the new trustee

(ii) Certificate of Incorporation

(iii) Articles of Incorporation

(iv) Registered address

(v) Business address (if different from the registered address)

III. Providing information regarding the controlling persons of the new trustee

(i) List of current directors

(ii) Identification documents and address vouchers (within three months) of the two directors who instructed the transfer of assets to the new trust, e.g. payment details.

(iii) If the transfer directed is not by the directors provided above, the following documents shall be provided:

① List of the new trustee’s authorized signer

② The consent resolution signed by an authorized signer of the new trustee

IV. Attorneys operating in the new trust’s jurisdiction draft a new trust agreement; the new trust agreement must indemnify the original trustee to allow for a smooth decanting.

V. A letter drafted for the original trustee explaining the reasons for the creation of a new trust and the transfer of assets to the new trust. Generally, this letter explains that the transfer is in the best interest of the trust’s beneficiaries and that the decanting would not trigger adverse tax consequences for the trust’s beneficiaries.

VI. The new trustee provides a signed asset transfer agreement, a deed of appointment and an indemnity.

VII. Attorneys operating in the new trust’s jurisdiction draft a legal validity opinion confirming the validity of the new trust under local laws and the new trustee’s capacity to act as trustee.

VIII. The new trustee confirms the tax liability of the original trust for the year in which assets are transferred to the new trust; this information will be reported by the new trustee the following year.

(4) Preparation of information required for the new trustees

I. Provide Original Trust Deed

II. Provide information related to the establishment of the new trust, such as background information on the original trust grantor and the source of wealth and funding (New Trust Information)

III. If the new trustee requires the beneficiary to sign a Release and Indemnity Agreement, it is important to note whether signing such an agreement creates a tax risk for the beneficiary.

IV. The original trustee is required to provide the new trustee with the Foreign Non-Grantor Trust Beneficiary Statement for the year:

(i) Background information on the foreign trust

(ii) Information of U.S. beneficiaries

(iii) Trust income distributed to U.S. beneficiaries

(iv) U.S. agent information of foreign trusts

(v) Types and amounts of proceeds transferred from the original foreign trust to the new U.S. trust