專業叢書

Estate Planning by U.S. Trust 美國報稅與海外財產揭露(英文部分)

Chapter 3 ─ U.S. Dynasty Trusts

Section 1: U.S. Trust Structure

There are few entities that can compare to a dynasty trust when it comes to transitioning familial wealth. As discussed in Chapter 1, many Asian family businesses are struggling with the proverbial “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations,” but wealthy non-Asian families face similar concerns. A study conducted by Merrill Lynch found that only 15% and 2% of families in East Asia successfully transition their families’ businesses to the second and third generations, respectively. Publicly available statistics in the U.S. aren’t more optimistic either. A survey conducted by U.S. Trust, a subsidiary of Bank of America found that 64% of wealthy individuals disclose little of their wealth to their children and 78% don’t feel that the next generation is financially responsible enough to handle the inheritance they are given.1 On the other hand, the Rockefeller family has managed to pass their fortune on for generations. The Rockefellers were the first family to establish a family office to manage their wealth. Through actively investing their vast family fortune through dynasty trusts, the Rockefellers have passed on their wealth to the seventh generation.

Many dynasty trusts are irrevocable “directed” trusts. A dynasty trust is primarily established for the benefit of one or more descendants (beneficiaries). The trust’s grantor appoints a trustee to manage the investment and administration of trust assets and distribute income or principal. Typically, a trust’s grantor also appoints a Trust Protector to make key decisions relating to the trust. This structure allows the grantor’s descendants to benefit from trust distributions without being able to take control of the trust’s assets.

1 Taylor, Chris (2015, June 17). 70% of Rich Families Lose Their Wealth by the Second Generation. Money. https://money.com/rich-families-lose-wealth/

A dynasty trust may also be structured as a grantor trust or non-grantor trust for U.S. income tax purposes. A trust is generally considered a “grantor trust” if the grantor is liable for paying income tax on the trust’s income. If the grantor is not liable for paying income taxes on the trust’s income, the trust is generally considered a “non-grantor trust.”

Under the U.S. federal income tax system, a U.S. trust is treated as a U.S. tax resident. The IRS defines a U.S. trust and foreign trust for federal income tax purposes under IRC §§ 7701(a)(30)(E) and (31)(B), effected in 1996. A trust is a U.S. trust when both of the following conditions are satisfied. A trust is considered a foreign trust if either of the following conditions is not satisfied:

I. A court within the U.S. is able to exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust (referred to as the Court Test);

II. One or more U.S. persons have the authority to control all substantial decisions of the trust (referred to as the Control Test)2.

2 26 U.S.C. § 7701 (a)(30)(E) (“the term ‘United Person’ means any trust if: (i) a court within the United States is able to exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust; and (ii) one or more United States persons have the authority to control all substantial decisions of the trust.”)

Thus, by definition, a U.S. trust is a trust governed by U.S. laws and has a U.S. controller. A foreign trust, on the other hand, is a trust established in the U.S. without a U.S. controller or a trust established outside of the U.S., regardless of whether the trust’s controller is a U.S. person, thus failing the court test or the control test. For U.S. federal income tax purposes, a foreign trust is regarded as a non-U.S. tax resident if the controller of the trust is a non-U.S. person. Thus, unless the foreign trust produces income effectively connected to the U.S., the trust will not be subject to U.S. income taxes.

We recommend that the person with the power to control all substantial decisions be the Trust Protector. The Trust Protector is, generally speaking, a fiduciary who holds many powers specified in a trust agreement.

In accordance with Treasury Reg. 301-7701-7(d)(2), if a U.S. trustee is replaced by a foreign trustee, the trust is allotted 12 months to replace the foreign trustee with a U.S. trustee to maintain U.S. trust status. If the change is not made within the 12 months specified, the trust will be considered a foreign trust the day the trustee changes to a non-U.S. trustee. 3

For example, if a New York resident creates a testamentary trust for his children by his will probated in New York, with a New York bank (a U.S. person) and an Irish cousin (a foreign person) acting as trustees. If principal distributions to the children can only be made by a majority vote of the trustees, the trust is a foreign trust under control test since a substantial decision is not controlled by a U.S. fiduciary. 4

3 26 CFR § 301.7701-7 (d)(2)(i).

4 G. Warren Whitaker, U.S. Tax Planning for Non-U.S. Persons and Trusts: An Introductory Outline (2012 Edition), p. 3.

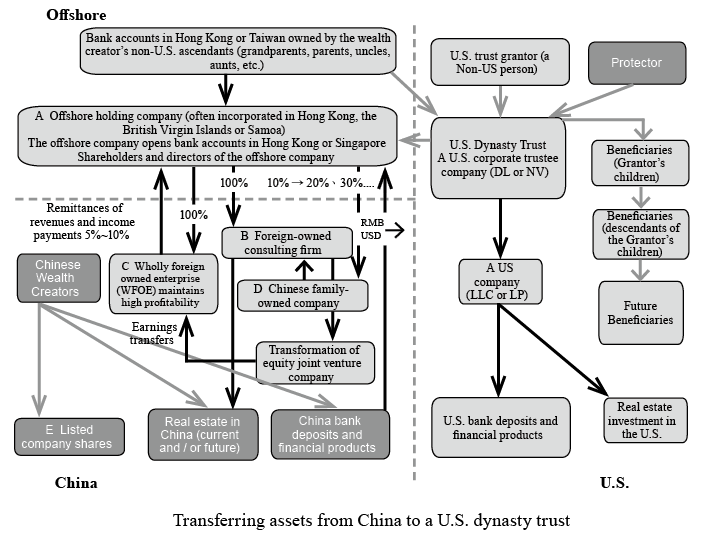

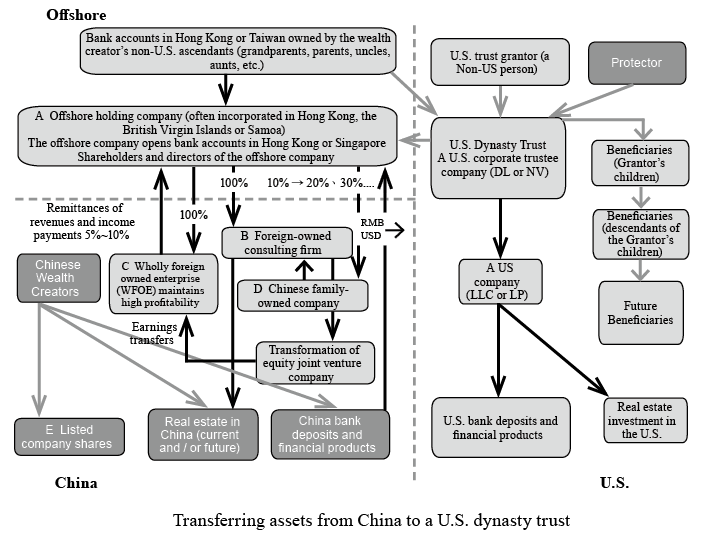

Grantors often hope to achieve many goals by setting up a dynasty trust. The most prevalent goals include protecting one’s assets, securing an inheritance for one’s descendants, saving taxes and transferring assets across countries. A grantor can achieve many objectives through the settling of a dynasty trust. The following example will illustrate a U.S. dynasty trust that accomplishes all of these goals.

Many dynasty trusts are irrevocable “directed” trusts. A dynasty trust is primarily established for the benefit of one or more descendants (beneficiaries). The trust’s grantor appoints a trustee to manage the investment and administration of trust assets and distribute income or principal. Typically, a trust’s grantor also appoints a Trust Protector to make key decisions relating to the trust. This structure allows the grantor’s descendants to benefit from trust distributions without being able to take control of the trust’s assets.

1 Taylor, Chris (2015, June 17). 70% of Rich Families Lose Their Wealth by the Second Generation. Money. https://money.com/rich-families-lose-wealth/

A dynasty trust may also be structured as a grantor trust or non-grantor trust for U.S. income tax purposes. A trust is generally considered a “grantor trust” if the grantor is liable for paying income tax on the trust’s income. If the grantor is not liable for paying income taxes on the trust’s income, the trust is generally considered a “non-grantor trust.”

Under the U.S. federal income tax system, a U.S. trust is treated as a U.S. tax resident. The IRS defines a U.S. trust and foreign trust for federal income tax purposes under IRC §§ 7701(a)(30)(E) and (31)(B), effected in 1996. A trust is a U.S. trust when both of the following conditions are satisfied. A trust is considered a foreign trust if either of the following conditions is not satisfied:

I. A court within the U.S. is able to exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust (referred to as the Court Test);

II. One or more U.S. persons have the authority to control all substantial decisions of the trust (referred to as the Control Test)2.

2 26 U.S.C. § 7701 (a)(30)(E) (“the term ‘United Person’ means any trust if: (i) a court within the United States is able to exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust; and (ii) one or more United States persons have the authority to control all substantial decisions of the trust.”)

Thus, by definition, a U.S. trust is a trust governed by U.S. laws and has a U.S. controller. A foreign trust, on the other hand, is a trust established in the U.S. without a U.S. controller or a trust established outside of the U.S., regardless of whether the trust’s controller is a U.S. person, thus failing the court test or the control test. For U.S. federal income tax purposes, a foreign trust is regarded as a non-U.S. tax resident if the controller of the trust is a non-U.S. person. Thus, unless the foreign trust produces income effectively connected to the U.S., the trust will not be subject to U.S. income taxes.

We recommend that the person with the power to control all substantial decisions be the Trust Protector. The Trust Protector is, generally speaking, a fiduciary who holds many powers specified in a trust agreement.

In accordance with Treasury Reg. 301-7701-7(d)(2), if a U.S. trustee is replaced by a foreign trustee, the trust is allotted 12 months to replace the foreign trustee with a U.S. trustee to maintain U.S. trust status. If the change is not made within the 12 months specified, the trust will be considered a foreign trust the day the trustee changes to a non-U.S. trustee. 3

For example, if a New York resident creates a testamentary trust for his children by his will probated in New York, with a New York bank (a U.S. person) and an Irish cousin (a foreign person) acting as trustees. If principal distributions to the children can only be made by a majority vote of the trustees, the trust is a foreign trust under control test since a substantial decision is not controlled by a U.S. fiduciary. 4

3 26 CFR § 301.7701-7 (d)(2)(i).

4 G. Warren Whitaker, U.S. Tax Planning for Non-U.S. Persons and Trusts: An Introductory Outline (2012 Edition), p. 3.

Grantors often hope to achieve many goals by setting up a dynasty trust. The most prevalent goals include protecting one’s assets, securing an inheritance for one’s descendants, saving taxes and transferring assets across countries. A grantor can achieve many objectives through the settling of a dynasty trust. The following example will illustrate a U.S. dynasty trust that accomplishes all of these goals.