Publications

U.S. Trust and Estate Planning 美國信託規劃實務(英文部分)

Chapter 3 U.S. Revocable Dynasty Trusts

By definition, a Revocable Trust is set up so that the Grantor retains the right to revoke the trust and reclaim assets held under the trust. While there are many forms of Revocable Trusts, this chapter focuses primarily on Revocable Trusts with non-U.S. Grantors.

By definition, a Revocable Trust is set up so that the Grantor retains the right to revoke the trust and reclaim assets held under the trust. While there are many forms of Revocable Trusts, this chapter focuses primarily on Revocable Trusts with non-U.S. Grantors.

Under U.S. tax law, a Foreign Grantor Trust (“FGT”) is a highly preferential trust structure for U.S. income tax purposes. A FGT settled in the U.S. (generally in Nevada or Delaware) by a non-U.S. person attributes income tax to the non-U.S. grantor of the trust for income tax purposes during the grantor’s lifetime. Thus, if an FGT were to hold only non-U.S. assets (with no U.S.-sourced income), it would generally not be taxable in the U.S. Any distribution from an FGT, if properly structured, would be tax-free to both U.S. and non-U.S. beneficiaries. U.S. beneficiaries of a FGT must file Form 3520, as the distributions are deemed to be gifts from a non-U.S. person for U.S. tax purposes.

Note: For a detailed explanation of the Form 3520, please refer to the section of Chapter 4 that discusses the Form 1040 (including Form 3520).

There are two conditions that can qualify a trust to be a Foreign Grantor Trust:

A FGT allows non-U.S. persons to place assets under U.S. protection without triggering U.S. income tax consequences during the grantor’s lifetime. Furthermore, if assets in the FGT are selected carefully and the grantor only places non-U.S. situs assets in the FGT, the trust would also not be subject to U.S. estate taxes upon the grantor’s death. Lastly, as the U.S. is not a participant in the Common Reporting Standards (CRS), as developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), information regarding assets held by a FGT established in the U.S. would not be shared with other countries, further protecting the privacy of the Wealth Creator.

Aside from relevant tax considerations, Wealth Creators also often seek to establish a Revocable Trust to designate specific beneficiaries. Though most Wealth Creators establish trusts to include their descendants as beneficiaries, some may choose to exclude certain descendants or others who may seek to claim their assets after their death.

Under U.S. tax law, a Foreign Grantor Trust (“FGT”) is a highly preferential trust structure for U.S. income tax purposes. A FGT settled in the U.S. (generally in Nevada or Delaware) by a non-U.S. person attributes income tax to the non-U.S. grantor of the trust for income tax purposes during the grantor’s lifetime. Thus, if an FGT were to hold only non-U.S. assets (with no U.S.-sourced income), it would generally not be taxable in the U.S. Any distribution from an FGT, if properly structured, would be tax-free to both U.S. and non-U.S. beneficiaries. U.S. beneficiaries of a FGT must file Form 3520, as the distributions are deemed to be gifts from a non-U.S. person for U.S. tax purposes.

Note: For a detailed explanation of the Form 3520, please refer to the section of Chapter 4 that discusses the Form 1040 (including Form 3520).

There are two conditions that can qualify a trust to be a Foreign Grantor Trust:

1. During the non-U.S. Grantor’s lifetime, his right to revoke the trust is unrestricted (a Revocable Trust).

2. During the non-US. Grantor’s lifetime, the only beneficiaries must be the Grantor and his spouse (an Irrevocable Trust).

A FGT allows non-U.S. persons to place assets under U.S. protection without triggering U.S. income tax consequences during the grantor’s lifetime. Furthermore, if assets in the FGT are selected carefully and the grantor only places non-U.S. situs assets in the FGT, the trust would also not be subject to U.S. estate taxes upon the grantor’s death. Lastly, as the U.S. is not a participant in the Common Reporting Standards (CRS), as developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), information regarding assets held by a FGT established in the U.S. would not be shared with other countries, further protecting the privacy of the Wealth Creator.

Aside from relevant tax considerations, Wealth Creators also often seek to establish a Revocable Trust to designate specific beneficiaries. Though most Wealth Creators establish trusts to include their descendants as beneficiaries, some may choose to exclude certain descendants or others who may seek to claim their assets after their death.

The roles in a Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT) may be customized to the family’s needs; however, the roles and responsibilities are similar in nature to those that are found in an U.S. Irrevocable Non-Grantor Trust with certain notable exceptions:

Note: For a detailed explanation of the remainder of the roles in a trust agreement, please refer to the section of Chapter 2 that discusses the roles and responsibilities of the trust’s fiduciaries.

1. The Grantor retains the right to revoke the trust, which makes the trust a revocable trust rather than an irrevocable trust.

2. The Grantor retains the right to distribute all (and any) of the trust assets to whomever during the grantor’s lifetime.

3. The trust agreement will have provisions that provide that the trust will remain a grantor trust unless the Grantor passes away or until the Grantor explicitly and unilaterally relinquish his right to revoke the trust. In either scenario, the trust will henceforth become an irrevocable trust.

4. The trust agreement would typically incorporate language that would facilitate the transition of the FGT to a U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust. This would be especially important if the trust has current or future U.S.-based beneficiaries.

Note: For a detailed explanation of the remainder of the roles in a trust agreement, please refer to the section of Chapter 2 that discusses the roles and responsibilities of the trust’s fiduciaries.

Assets held in a Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT) shift income tax liability from the trust to the Grantor (non-U.S. person) for U.S. income tax purposes. As such, for both U.S. and non-U.S. assets, the Grantor of the trust is viewed as the income taxpayer for U.S. income tax purposes.

When a foreigner (a non-U.S. person) holds non-U.S. assets, he is generally not liable for U.S. income tax (on income not “effectively connected” to the U.S.); however, when a foreigner holds U.S. assets, he is liable for U.S. income tax (often at a considerable higher tax rate than a U.S. person). As such, almost all assets placed in FGTs are non-U.S. assets.

It is often recommended that clients place interest in non-U.S. holding and / or operating companies into FGTs. These assets primarily consist of offshore companies established in offshore jurisdictions, including the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Cayman Islands, Samoa, or other countries.

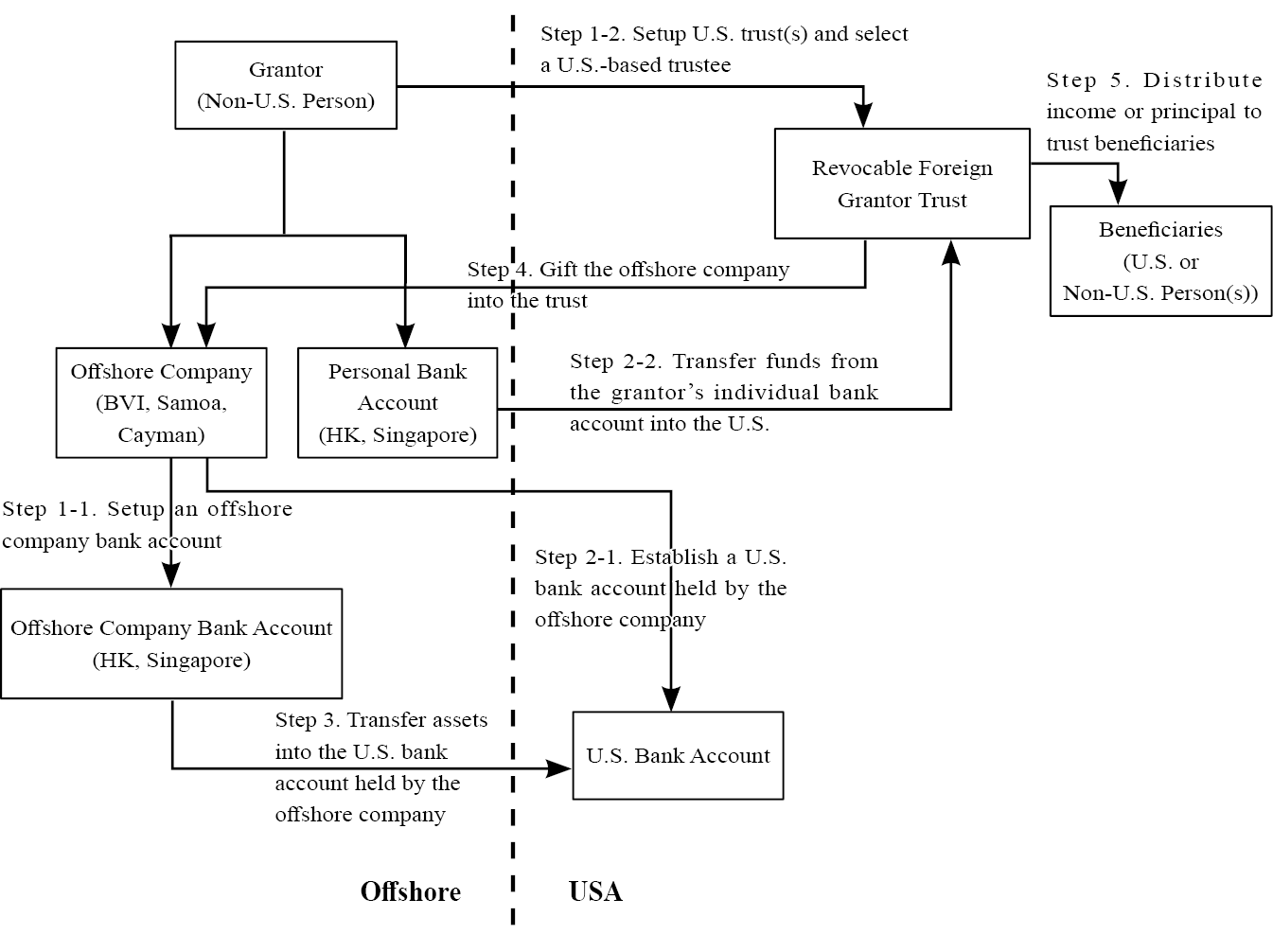

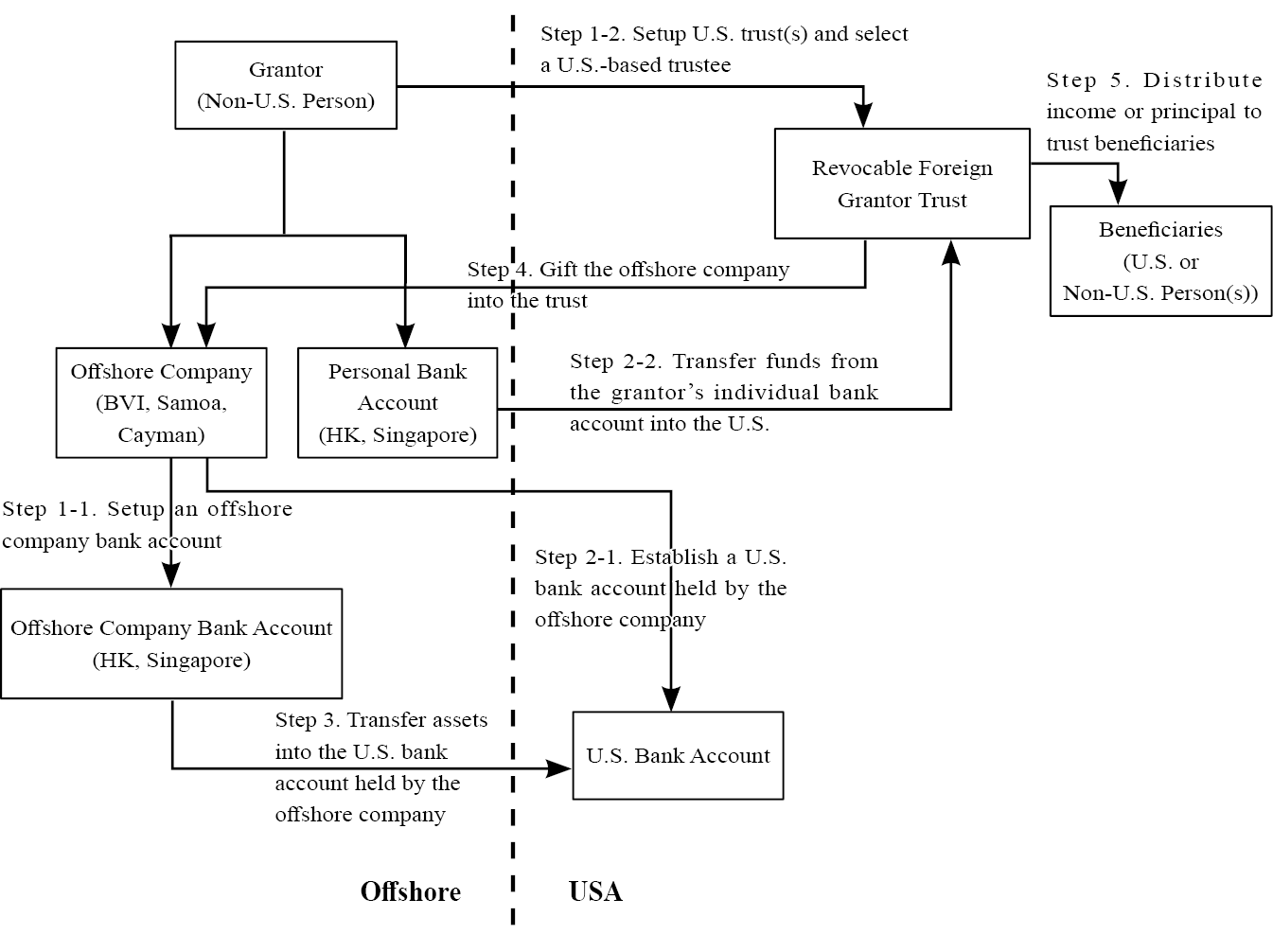

Could you provide an example of a Foreign Grantor Trust structure?

When a foreigner (a non-U.S. person) holds non-U.S. assets, he is generally not liable for U.S. income tax (on income not “effectively connected” to the U.S.); however, when a foreigner holds U.S. assets, he is liable for U.S. income tax (often at a considerable higher tax rate than a U.S. person). As such, almost all assets placed in FGTs are non-U.S. assets.

It is often recommended that clients place interest in non-U.S. holding and / or operating companies into FGTs. These assets primarily consist of offshore companies established in offshore jurisdictions, including the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Cayman Islands, Samoa, or other countries.

Could you provide an example of a Foreign Grantor Trust structure?

An NRA is subject to gift and estate tax only on U.S. situs assets. However, domicile for U.S. gift and estate tax purposes is defined differently than that for U.S. income tax purposes. Unlike the substantial presence test for income tax purposes, which is generally based on the number of days one spends in the U.S., domicile for U.S. gift and estate tax purposes centers around being physically present in the U.S. and intending to permanently remain in the U.S. An individual can be deemed an income tax resident but not have a domicile in the U.S. and vice versa.

Whether an individual is deemed to remain permanently in the U.S. is a facts and circumstances test. The IRS characterizes the following as facts that may point to a U.S. domicile:

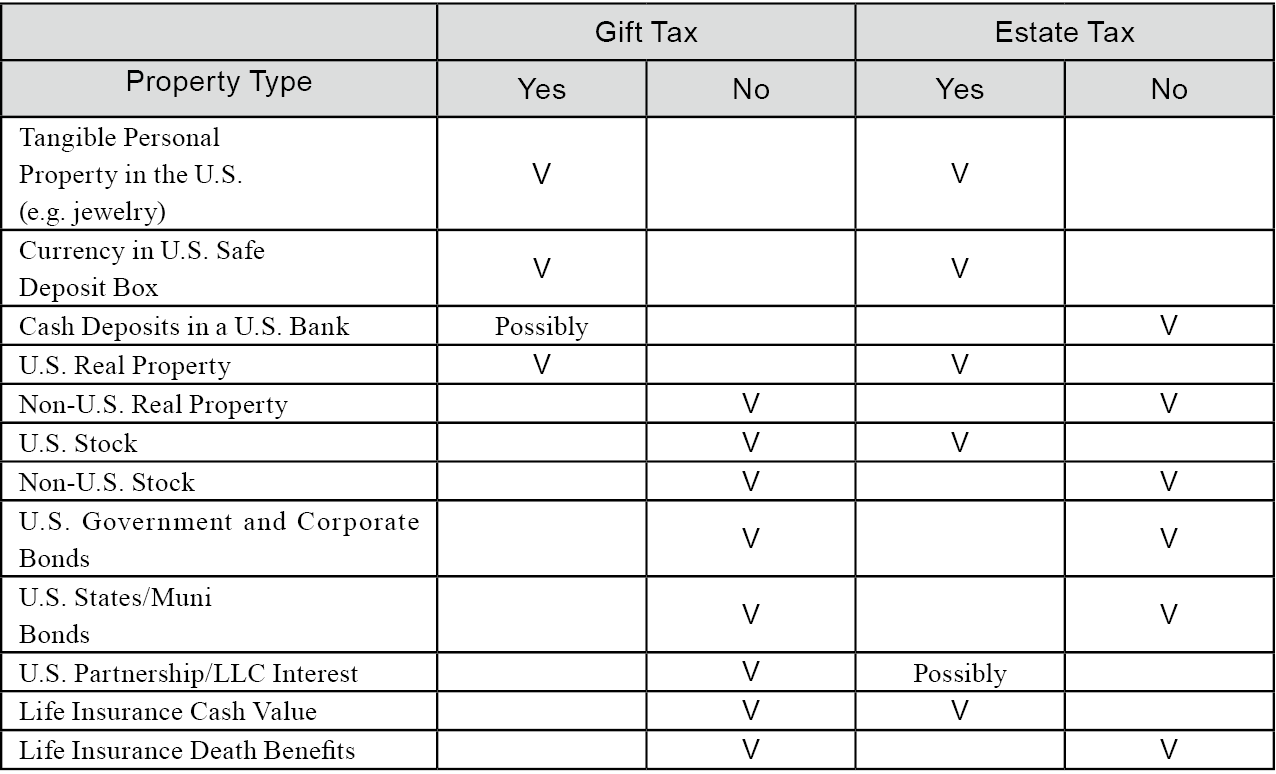

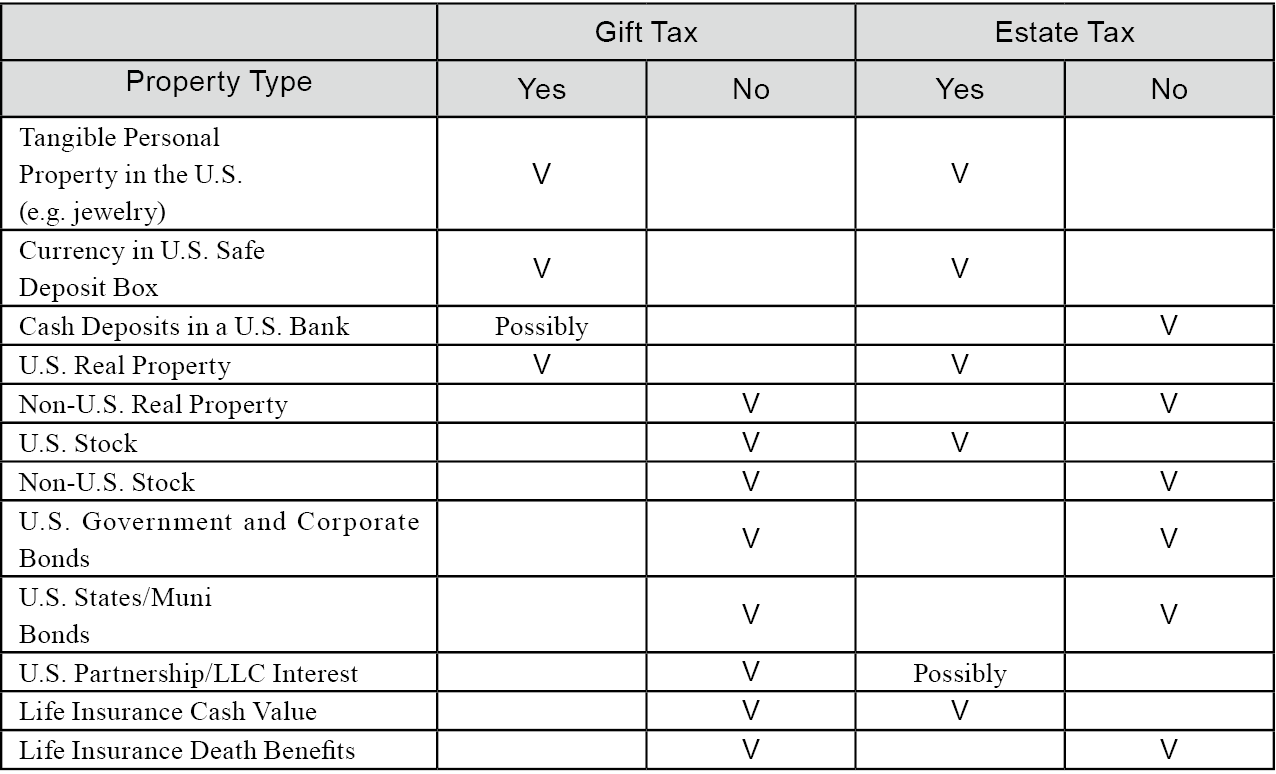

The IRS has defined assets that are and are not subject to U.S. gift and estate taxes when they are transferred by an individual who does not have a U.S. domicile. Assets that do trigger U.S. gift and estate taxes are generally termed assets with a U.S. situs.

The categorization of assets is different for U.S. estate and gift taxes. The following chart categorizes assets as those generally subject to U.S. gift tax, U.S. estate tax or both, when they are transferred from a person without a U.S. domicile.

Whether an individual is deemed to remain permanently in the U.S. is a facts and circumstances test. The IRS characterizes the following as facts that may point to a U.S. domicile:

- Where does the individual pay state income tax?

- Where does the individual vote?

- Where does the individual own property?

- Where is the individual’s citizenship?

- How long is the individual length of residence?

- Where is the individual’s business based?

- Where does the individual have social ties to his or her community?

The IRS has defined assets that are and are not subject to U.S. gift and estate taxes when they are transferred by an individual who does not have a U.S. domicile. Assets that do trigger U.S. gift and estate taxes are generally termed assets with a U.S. situs.

The categorization of assets is different for U.S. estate and gift taxes. The following chart categorizes assets as those generally subject to U.S. gift tax, U.S. estate tax or both, when they are transferred from a person without a U.S. domicile.

While we generally recommend that clients stray away from establishing offshore trusts (defined herein as trusts settled outside of the U.S.), particularly if they have U.S. descendants, Wealth Creators who previously established offshore trusts should familiarize themselves with Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT) rules. Offshore trusts include trusts settled in the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Cayman Islands, Bahamas, Bermuda, Switzerland, Cook Islands, Jersey, Nevis, or any other non-U.S. jurisdiction.

When a U.S. person is a beneficiary of a foreign trust, the tax consequences are generally quite punitive (often involving “throwback” taxes for distributions of undistributed net income (“UNI”). Oftentimes, when offshore trusts are established, the tax consequences of future distributions are not adequately analyzed by the recommending party (frequently non-U.S. financial advisors and bankers at non-U.S. financial institutions).

Offshore trusts are also frequently established prior to the grantor either having U.S. person beneficiaries or prior to the grantor disclosing their U.S. person beneficiaries. Wealth Creators should be extremely wary of this, as non-U.S. financial institutions tend to downplay the tax impact of trusts with U.S. beneficiaries or, in certain cases, choose to outright ignore the fact that the trust has U.S. persons.

Offshore trust companies typically retain many powers rather than stipulating that the family itself would control the trust. Sometimes, offshore trust agreements may also stipulate that the trustee would not be able to be removed barring certain exceptions. While this allows these trust companies to improve client retention, the Wealth Creator’s family oftentimes lacks powers necessary to govern the trust.

Furthermore, the drafting of these trust agreements often leads to the Wealth Creator directing the offshore trustee to manage investments and distributions using Letters of Wish. While the Wealth Creator may feel like he or she is in charge of all functions of the trust, the trust could be deemed a sham trust if any lawsuit were to arise, leading to the trust’s asset protection powers to be severely eroded.

In sharp contrast, Foreign Grantor Trusts established in the U.S. generally have explicitly defined powers for the trust’s fiduciaries (trust protector, investment direction advisor, and distribution advisor), which allows the family to both stay in control of trust assets and swap out trustees if necessary. In addition, since the roles and responsibilities are generally set forth clearly in the trust agreement, it is extremely unlikely that the trust could be deemed a sham trust by outside creditors.

For Wealth Creators that had the foresight to adequately review and / or modify their offshore trusts, they often have them structured as Foreign Grantor Trusts (under certain circumstances, offshore trusts may qualify as FGTs as well). When doing so, Wealth Creators should undoubtedly seek U.S. tax advice from competent counsel.

Wealth Creators with offshore trusts should take steps to mitigate the risk of their trusts being deemed sham trusts by clearly delineating the powers assigned to each of the trust’s fiduciaries in the trust agreement. If this cannot be done, the Wealth Creator should consider establishing a new trust and decanting (transferring) assets from the old trust to the new trust.

When a U.S. person is a beneficiary of a foreign trust, the tax consequences are generally quite punitive (often involving “throwback” taxes for distributions of undistributed net income (“UNI”). Oftentimes, when offshore trusts are established, the tax consequences of future distributions are not adequately analyzed by the recommending party (frequently non-U.S. financial advisors and bankers at non-U.S. financial institutions).

Offshore trusts are also frequently established prior to the grantor either having U.S. person beneficiaries or prior to the grantor disclosing their U.S. person beneficiaries. Wealth Creators should be extremely wary of this, as non-U.S. financial institutions tend to downplay the tax impact of trusts with U.S. beneficiaries or, in certain cases, choose to outright ignore the fact that the trust has U.S. persons.

Offshore trust companies typically retain many powers rather than stipulating that the family itself would control the trust. Sometimes, offshore trust agreements may also stipulate that the trustee would not be able to be removed barring certain exceptions. While this allows these trust companies to improve client retention, the Wealth Creator’s family oftentimes lacks powers necessary to govern the trust.

Furthermore, the drafting of these trust agreements often leads to the Wealth Creator directing the offshore trustee to manage investments and distributions using Letters of Wish. While the Wealth Creator may feel like he or she is in charge of all functions of the trust, the trust could be deemed a sham trust if any lawsuit were to arise, leading to the trust’s asset protection powers to be severely eroded.

In sharp contrast, Foreign Grantor Trusts established in the U.S. generally have explicitly defined powers for the trust’s fiduciaries (trust protector, investment direction advisor, and distribution advisor), which allows the family to both stay in control of trust assets and swap out trustees if necessary. In addition, since the roles and responsibilities are generally set forth clearly in the trust agreement, it is extremely unlikely that the trust could be deemed a sham trust by outside creditors.

For Wealth Creators that had the foresight to adequately review and / or modify their offshore trusts, they often have them structured as Foreign Grantor Trusts (under certain circumstances, offshore trusts may qualify as FGTs as well). When doing so, Wealth Creators should undoubtedly seek U.S. tax advice from competent counsel.

Wealth Creators with offshore trusts should take steps to mitigate the risk of their trusts being deemed sham trusts by clearly delineating the powers assigned to each of the trust’s fiduciaries in the trust agreement. If this cannot be done, the Wealth Creator should consider establishing a new trust and decanting (transferring) assets from the old trust to the new trust.

Historically, many Asian Wealth Creators did not view the U.S. as a viable jurisdiction in which to establish trusts. As such, many families opted for offshore trusts (trusts established outside of the U.S.), perceiving the tax and disclosure requirements for those jurisdictions as less risky or stringent.

While establishing offshore trusts may satisfy certain Wealth Creators that have no U.S. ties (assets or descendants), the vast majority of Asian Wealth Creators have certain ties to the U.S. Specifically, if their descendants become U.S. persons or live in the U.S., offshore trusts are generally not as suitable as certain U.S.-based trusts.

Aside from tax consequences, many offshore trust agreements also contain language that unnecessarily restrict the family’s control over the trust’s assets. Trustees of offshore trusts often have immense control over the trusts they administer. Furthermore, the trust agreement’s language is often static, and Wealth Creators are frequently convinced to “just sign” instead of reviewing all the trust agreement’s terms and suggesting changes. By doing so, Wealth Creators and their families may face considerable and unexpected obstacles when managing their offshore trusts.

Luckily, many Wealth Creators are able to transfer assets held in their offshore trust into a U.S.-based trust in a process typically called decanting. Decanting is especially important for families with investments in the U.S. or family members based in the U.S.

When initiating a decanting, Wealth Creators may face considerable resistance from their offshore trust’s trustee (typically an offshore trust company) and the Wealth Creator’s non-U.S. financial advisors (typically employed by a non-U.S. financial institution), both of whom could impose obstacles to such a transfer. The reluctance to transferring assets can typically be attributed to the loss of future revenues from the account, including both investment management fees and trust administration service fees. To facilitate a seamless transition and an efficient timeline, experienced advisors should be retained to negotiate on the family’s behalf.

When decanting assets from an offshore trust to a U.S. trust, the Wealth Creator should prepare the following documents for original and new trustees, respectively:

Original Trustee(s)

New Trustee(s)

While establishing offshore trusts may satisfy certain Wealth Creators that have no U.S. ties (assets or descendants), the vast majority of Asian Wealth Creators have certain ties to the U.S. Specifically, if their descendants become U.S. persons or live in the U.S., offshore trusts are generally not as suitable as certain U.S.-based trusts.

Aside from tax consequences, many offshore trust agreements also contain language that unnecessarily restrict the family’s control over the trust’s assets. Trustees of offshore trusts often have immense control over the trusts they administer. Furthermore, the trust agreement’s language is often static, and Wealth Creators are frequently convinced to “just sign” instead of reviewing all the trust agreement’s terms and suggesting changes. By doing so, Wealth Creators and their families may face considerable and unexpected obstacles when managing their offshore trusts.

Luckily, many Wealth Creators are able to transfer assets held in their offshore trust into a U.S.-based trust in a process typically called decanting. Decanting is especially important for families with investments in the U.S. or family members based in the U.S.

When initiating a decanting, Wealth Creators may face considerable resistance from their offshore trust’s trustee (typically an offshore trust company) and the Wealth Creator’s non-U.S. financial advisors (typically employed by a non-U.S. financial institution), both of whom could impose obstacles to such a transfer. The reluctance to transferring assets can typically be attributed to the loss of future revenues from the account, including both investment management fees and trust administration service fees. To facilitate a seamless transition and an efficient timeline, experienced advisors should be retained to negotiate on the family’s behalf.

When decanting assets from an offshore trust to a U.S. trust, the Wealth Creator should prepare the following documents for original and new trustees, respectively:

Original Trustee(s)

1. Background information regarding the new trust (the trust assets will be decanted into):

-

- the name of the new trust

- the name and address of the new trustee

- the date the new trust was established

- the U.S. tax identification number (EIN) of the new trust

2. Background information regarding the new Trustee:

-

- the name of the new Trustee

- the contact information of the new Trustee

- other background information required of the original Trustee

3. The structure of the new trust agreement:

-

- a list of the new trust’s fiduciaries

- background information of the new trust’s fiduciaries (including identification documents and background checks)

- a list of authorized signers in the new trust

- any consent to accept trust assets by the new trustee

4. Other required information:

-

- the contact information of drafting attorneys in the new trust’s jurisdiction

- documents indemnifying the original trustee for legal responsibility over the decanting

- a memo detailing the rationale for the creation of the new trust (this would generally state that decanting the trust assets is in the best interest of the trust’s beneficiaries)

- a memo discussing the tax ramifications of decanting the assets to the trust’s new jurisdiction (often provided by a tax attorney)

- an asset transfer agreement whereby assets to be transferred are listed

New Trustee(s)

1. The notarized version of the original trust agreement (electronic copies are often acceptable)

2. Information regarding the new trust agreement:

-

- the new trust agreement, as drafted by a competent attorney in the new trust jurisdiction

- background information regarding the new trusts’ Grantor(s), fiduciaries and beneficiaries (including identification information)

- information regarding the Grantor’s sources of wealth

- information regarding the assets being transferred to the new trust

3. A release and indemnity agreement signed by the beneficiaries (if required)

4. A Beneficiary Statement for the previous year prepared by the original Trustee detailing:

-

- background information on the original trust

- known information regarding the original trusts’ beneficiaries

- any trust income previously distributed to the original trusts’ beneficiarie

- the types of assets held by the original trust agreement

- information regarding any funds held directly by the original trust

When the grantor of a Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT) dies, the trust generally becomes irrevocable. Depending on the language of the trust agreement, the trust either becomes a U.S. irrevocable trust or a foreign irrevocable trust, as determined by the Control Test and Court Test (described in length in the previous chapter).

As the grantor is no longer alive, the trust typically becomes a non-grantor trust and becomes its own taxable entity for U.S. income tax purposes. Assets held by the FGT are generally only taxable for U.S. estate tax purposes to the extent that trust assets possess U.S. situs.

For Wealth Creators with U.S.-person beneficiaries, it is extremely important to note that these two types of trusts fall under vastly different U.S. income tax regimes. Clients should seek competent U.S. tax counsel in determining the most favorable form of taxation and have the FGT trust agreement drafted accordingly. Both the drafting attorney and the tax attorney should review and sign off on the final version of the trust agreement. This can ensure that the trust agreement is optimized for the client’s specific needs, the trust jurisdiction’s state laws, and U.S. tax consequences.

Generally speaking, it is advisable that Wealth Creators with U.S. beneficiaries consider language that would effectively convert a FGT into a U.S. irrevocable trust, rather than a foreign irrevocable trust, upon the grantor’s death. Typically, if this is the grantor’s intent, the trust agreement would incorporate language that would allow it to fulfill the Control Test and Court Test immediately upon the grantor’s death.

Even if the trust does not immediately fulfill both the Control Test and the Court Test, thereby becoming a U.S. trust, it generally has one year to fulfill both and “cure” itself of foreign trust status. Thus, the trust would be treated as a U.S. trust from the day the grantor deceases, thereby relieving the trust of foreign trust status for U.S. tax purposes for the period between the grantor’s death and the time it fulfills both the Control and Court Tests in accordance with Regs. Sec. 301.7701-7(d)(2).

After converting the trust to a U.S. irrevocable trust, all trust income is generally taxed on a current basis, which could avoid any “throwback” taxes that may arise for trusts treated as foreign trusts.

As the grantor is no longer alive, the trust typically becomes a non-grantor trust and becomes its own taxable entity for U.S. income tax purposes. Assets held by the FGT are generally only taxable for U.S. estate tax purposes to the extent that trust assets possess U.S. situs.

For Wealth Creators with U.S.-person beneficiaries, it is extremely important to note that these two types of trusts fall under vastly different U.S. income tax regimes. Clients should seek competent U.S. tax counsel in determining the most favorable form of taxation and have the FGT trust agreement drafted accordingly. Both the drafting attorney and the tax attorney should review and sign off on the final version of the trust agreement. This can ensure that the trust agreement is optimized for the client’s specific needs, the trust jurisdiction’s state laws, and U.S. tax consequences.

Generally speaking, it is advisable that Wealth Creators with U.S. beneficiaries consider language that would effectively convert a FGT into a U.S. irrevocable trust, rather than a foreign irrevocable trust, upon the grantor’s death. Typically, if this is the grantor’s intent, the trust agreement would incorporate language that would allow it to fulfill the Control Test and Court Test immediately upon the grantor’s death.

Even if the trust does not immediately fulfill both the Control Test and the Court Test, thereby becoming a U.S. trust, it generally has one year to fulfill both and “cure” itself of foreign trust status. Thus, the trust would be treated as a U.S. trust from the day the grantor deceases, thereby relieving the trust of foreign trust status for U.S. tax purposes for the period between the grantor’s death and the time it fulfills both the Control and Court Tests in accordance with Regs. Sec. 301.7701-7(d)(2).

After converting the trust to a U.S. irrevocable trust, all trust income is generally taxed on a current basis, which could avoid any “throwback” taxes that may arise for trusts treated as foreign trusts.

Form 8832 Election (step up basis)

Assets in the FGT ae includible in the grantor’s estate for U.S. estate tax purposes. Any capital gains held in the trust may be “stepped up” to fair market value through a “deemed liquidation” immediately prior to the grantor’s death by filing an entity classification election (Form 8832). This election may be activated retroactively, subject to certain limitations.

Note: For a detailed explanation of entity classification elections, please refer to the section of Chapter 4 that discusses the Form 8832

U.S. Tax Treatment for Foreign Estates

Under certain circumstances, assets held in a FGT may also be treated as being held by a foreign estate rather than a U.S. trust. When properly structured, this tax treatment may defer or alleviate U.S. income taxes for a period of time not exceeding two years. This could allow for the foreign estate to realize income without incurring U.S. income taxes.

Assets in the FGT ae includible in the grantor’s estate for U.S. estate tax purposes. Any capital gains held in the trust may be “stepped up” to fair market value through a “deemed liquidation” immediately prior to the grantor’s death by filing an entity classification election (Form 8832). This election may be activated retroactively, subject to certain limitations.

Note: For a detailed explanation of entity classification elections, please refer to the section of Chapter 4 that discusses the Form 8832

U.S. Tax Treatment for Foreign Estates

Under certain circumstances, assets held in a FGT may also be treated as being held by a foreign estate rather than a U.S. trust. When properly structured, this tax treatment may defer or alleviate U.S. income taxes for a period of time not exceeding two years. This could allow for the foreign estate to realize income without incurring U.S. income taxes.