Publications

Estate Planning by U.S. Trust 美國報稅與海外財產揭露(英文部分)

Chapter 1 ─ The Meaning of Inheritance

傳承意義與案例

In Chinese, Chuan (傳) refers to the act of passing things on and Cheng (承) refers to the act of taking charge. Thus, Chuan Cheng (傳承) refers to the process by which certain assets, skills and doctrines are passed from one party to another. Before discussion about familial succession, we must first understand the concepts of family, familial wealth and their relationship.

A family is created when two or more individuals are linked by kinship, blood or emotions. A family’s wealth is composed of values, ideas, intangible assets and tangible property. While there is not a single metric by which we can measure the relative successes of transferring a family’s wealth from one generation to another, we generally consider familial wealth transfering across more than four generaions (~120 years) to be a successful Chuan Cheng(傳承).

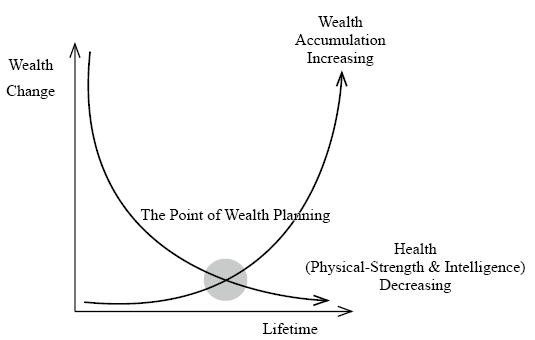

Families often fail to pass on their wealth from one generation to the next for similar reasons. From our perspective, the most common reason for the failure to pass on familial wealth is the failure to recognize the need to plan for intergenerational wealth transitions. In prior generations, Wealth Creators have been keenly aware that their time is limited and that they must find ways to pass on their wealth before their death; however, in recent years, medical advances have made matters worse by giving Wealth Creators an often overestimated sense of security regarding their health and how much more time they have to transition their wealth.

In the early to mid-1900s, life expectancy in the U.S. hovered between 55 and 65 years old. Nowadays, due to medical advances, many live until they are 80-90 years old. As a result, while many Wealth Creators put off the transition until much later on in their lives, many have also taken the opportunity to pass on their knowledge to the next generation and their third generation. Thus, the concepts of and theories behind Chuan Cheng (傳承) have become increasingly important as transitions of wealth and knowledge is spread out on a longer time horizon and with more opportunities to plan for the future.

A family is created when two or more individuals are linked by kinship, blood or emotions. A family’s wealth is composed of values, ideas, intangible assets and tangible property. While there is not a single metric by which we can measure the relative successes of transferring a family’s wealth from one generation to another, we generally consider familial wealth transfering across more than four generaions (~120 years) to be a successful Chuan Cheng(傳承).

Families often fail to pass on their wealth from one generation to the next for similar reasons. From our perspective, the most common reason for the failure to pass on familial wealth is the failure to recognize the need to plan for intergenerational wealth transitions. In prior generations, Wealth Creators have been keenly aware that their time is limited and that they must find ways to pass on their wealth before their death; however, in recent years, medical advances have made matters worse by giving Wealth Creators an often overestimated sense of security regarding their health and how much more time they have to transition their wealth.

In the early to mid-1900s, life expectancy in the U.S. hovered between 55 and 65 years old. Nowadays, due to medical advances, many live until they are 80-90 years old. As a result, while many Wealth Creators put off the transition until much later on in their lives, many have also taken the opportunity to pass on their knowledge to the next generation and their third generation. Thus, the concepts of and theories behind Chuan Cheng (傳承) have become increasingly important as transitions of wealth and knowledge is spread out on a longer time horizon and with more opportunities to plan for the future.

1. Why do intergenerational wealth transfers fail?

The following is an excerpt from Chinese folklore: Families that are able to pass on their core values can remain wealthy for more than ten generations. Families with ambition and perseverance can grow their wealth indefinitely but the wealth will not last longer than in those families that understand the importance their core values and principles. Families who are indecisive and irresponsible will quickly cease to pass on their wealth. Heirs who solely rely on their parents will inevitably lose their family’s wealth before the third generation.

Mencius, a Chinese Confucian philosopher, once said, “A man’s wealth cannot be preserved for more than five generations.” The word Ze (澤) means “rain and dew”, but also symbolizes the fruits of a family’s business; the word Zhan (斬) means “cut off”, but also symbolizes the decay of a family’s business.

“The motivation to achieve success dwindles as the sense of entitlement rises through each generation. If future generations do not find their own field of expertise, wealth generated by prior generations will only allow them to indulge in poor life choices.” Passing down a family’s principles is thus significantly more important than passing down a family’s fortune.

The author’s grandfather was born in the Qing Dynasty. He grew up and studied during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan and passed away after World War II. He dabbled in philosophy and proposed family wealth succession theories over 100 years ago. He theorized that if even one generation fails to preserve wealth, the transition of wealth will be shortened significantly.

Over the past three decades, the author has helped many families with succession planning and come to realize the various reasons why familial wealth succession generally fails.

The prophesy of the three generations is as follows:

A successful Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “First Generation” in Asia, most often marks the peak of a family’s wealth and economic status. The “classic” first generation refuses to live in luxury but prefers a modest lifestyle, driving a single car for many years and flying in economy. Born with a passion to understand their surroundings, they seek to singlehandedly make something of themselves and are able to grasp opportunities. Their modest upbringing, exhaustive diligence and multifaceted talents allow them to generate a rather significant sum of wealth in their lifetimes.

The children of the Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “Second Generation” in Asia, often focus on growing and preserving the family’s wealth, accomplishments and status. As they grow up, they learn from the Wealth Creators directly and are mostly able to continue familial ethics and rituals. Since most of the second generation realize that they are not as gifted as their predecessors, they tone down their lifestyles around their ascendants but live a moderately comfortable life nevertheless.

The children of the second generation, commonly referred to as the “Third Generation” in Asia, often remove themselves from the preservation of wealth altogether. The third generation often grow up in an environment ill fitted for learning the difficult task of preserving the family’s wealth and status. Since the minute they were born, they are endowed a luxurious lifestyle without a care in the world. This breeds shortsightedness, leading many in the third generation to believe that money can buy happiness.

Studies also show that passing wealth on for more than three generations is indeed a challenge for many families.

(1) A survey conducted by U.S. Trust, a subsidiary of Bank of America, found that 64% of wealth creators disclosed little of their wealth to their children and 78% feel that the next generation is not financially responsible enough to handle assets they are given.

(2) A separate study conducted by Merrill Lynch found that only 15% and 2% of families in East Asia successfully transition their family businesses to the second and third generations, respectively.

(3) In 2017, CNBC reported that, “one-third of Asia’s wealth may change hands in the next five years.” It reported that many families will see their wealth reduced due to familial disputes and transition taxes.

2. Types of Wealth Creators and the problem they face

Wealth Creators often work their entire lives dedicated to their profession. By starting early and integrating their succession plan with their businesses, they can expand upon their creations and build a lasting legacy, one that incorporates their family, their employees and society at large. Wealth Creators who fail to invest adequate time and energies in creating and protecting their legacies often leave behind lasting familial disputes, shareholder disagreements, employee distress and unnecessary conflict various judicial and administrative organizations. As a Wealth Creator, you must ask yourself, “Who is my successor?” After all, the first step in familial succession is choosing a viable successor.

After meeting with many Wealth Creators, the author has come to the conclusion that the main reason they fail to act is because they fear that their actions would lead to succession inequality. Thus, they shy away from discussing or planning their legacies. Generally, Wealth Creators can be categorized into the four following categories:

If you are a potential successor and become aware of your family’s assets, you may want to consider which category your ascendants belong under. This could potentially determine your next course of action. After thinking about your ascendants, you should also think about your role in the family. Generally, the second generation falls in one of the following categories:

(1) The second generation often have less pronounced Asian values. This is especially true of descendants who have lived abroad for many years or those who started families outside of Asia. Although they are of Asian descent, they identify more closely with Western values and focus more on realizing personal goals rather than strengthening the family business and thinking on behalf of the greater family at large.

(2) The second generation may not need financial support from their families: they are often efficient workers, enjoying high socioeconomic statuses wherever they settle. Many may play an active role in their communities. Some second generation are even financially independent and live comfortably even without their families’ assets. They may not want or need wealth created by their ascendants and the responsibilities that come with that wealth. For this category of second generation, their family’s various businesses and assets could actually end up becoming a sizable burden rather than an asset.

(3) Some second generation may lack the foresight or strategic direction necessary to continue the family business. Familial disputes may arise if the second generation refuses to make decisions regarding the family business. Relationships with longstanding employees in the family business may also falter as a result of inaction or poor decision-making. The author believes that the second generation should hold themselves responsible for their family’s business, whether they choose to manage it themselves or have others manage it on their behaves.

While many Wealth Creators and their descendants want to transition their family businesses and other assets to the next generation, four major points of contention generally arise when they begin to consider succession:

(1) Transfer Costs

In many jurisdictions, there is a significant cost related to the transfer of assets from one generation to the next, especially if the assets transferred are sizable. For example, the highest intergenerational transfer tax rates in Taiwan, the United States and Japan can run as high as 20%, 40%3 and 55%, respectively. As it stands, according to various online sources, the transfer tax rate in China is slated to be implemented at 50%.

3 Excludes U.S. generation-skipping taxes (GST).(此處40%不含美國隔代移轉稅)。

(2) Succession Disputes

Succession disputes may arise as a result of a number of factors, often exacerbated by a lack of prior planning by the Wealth Creator before he or she is incapacitated. Typically, the second generation either dispute ① the assets they are entitled to or ② the various business responsibilities delegated to them.

When the first generation fails to create a comprehensive succession plan, the family business and other familial assets are often hurriedly passed on. The second generation, often unaware of the situation prior to the Wealth Creator’s death or incapacity, may be woefully unprepared to singlehandedly handle familial businesses and affairs.

The use of nominal holders of assets, commonly referred to as “nominees,” a common tactic in Asia, may only serve to further complicate the situation. If a nominee passes away or become incapacitated, the transfer of assets to the second generation may become fraught with additional expenses and challenges. It is common that disputes (either in or out of court) with nominees significantly reduce the assets passed to the second generation.

(3) Debt Disputes

While debt is instrumental in many businesses’ growth, it can also be a source of disputes during a family’s wealth transition from one generation to the next. With a larger scale comes larger profits; however, disputes regarding the legitimate owner(s) of a family’s assets and liabilities may be exacerbated by the existence of significant outstanding debts. A family’s equity can quickly be reduced if the family lacks the ability to pay either the interest expense of debt or the balloon payment upon maturity.

(4) Differences in Familial Focus and Values

The second generation often focus on different aspects of life, when compared to the Wealth Creators. While the Wealth Creator may be concerned about his or her profits and legacy, his or her descendants can focus on their time and energies on pursuing matters of interest to them rather than the profitability of the family’s businesses. Thus, without adequate and timely communication, familial values and virtues will likely not stand the test of time.

The following is an excerpt from Chinese folklore: Families that are able to pass on their core values can remain wealthy for more than ten generations. Families with ambition and perseverance can grow their wealth indefinitely but the wealth will not last longer than in those families that understand the importance their core values and principles. Families who are indecisive and irresponsible will quickly cease to pass on their wealth. Heirs who solely rely on their parents will inevitably lose their family’s wealth before the third generation.

Mencius, a Chinese Confucian philosopher, once said, “A man’s wealth cannot be preserved for more than five generations.” The word Ze (澤) means “rain and dew”, but also symbolizes the fruits of a family’s business; the word Zhan (斬) means “cut off”, but also symbolizes the decay of a family’s business.

“The motivation to achieve success dwindles as the sense of entitlement rises through each generation. If future generations do not find their own field of expertise, wealth generated by prior generations will only allow them to indulge in poor life choices.” Passing down a family’s principles is thus significantly more important than passing down a family’s fortune.

The author’s grandfather was born in the Qing Dynasty. He grew up and studied during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan and passed away after World War II. He dabbled in philosophy and proposed family wealth succession theories over 100 years ago. He theorized that if even one generation fails to preserve wealth, the transition of wealth will be shortened significantly.

Over the past three decades, the author has helped many families with succession planning and come to realize the various reasons why familial wealth succession generally fails.

The prophesy of the three generations is as follows:

A successful Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “First Generation” in Asia, most often marks the peak of a family’s wealth and economic status. The “classic” first generation refuses to live in luxury but prefers a modest lifestyle, driving a single car for many years and flying in economy. Born with a passion to understand their surroundings, they seek to singlehandedly make something of themselves and are able to grasp opportunities. Their modest upbringing, exhaustive diligence and multifaceted talents allow them to generate a rather significant sum of wealth in their lifetimes.

The children of the Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “Second Generation” in Asia, often focus on growing and preserving the family’s wealth, accomplishments and status. As they grow up, they learn from the Wealth Creators directly and are mostly able to continue familial ethics and rituals. Since most of the second generation realize that they are not as gifted as their predecessors, they tone down their lifestyles around their ascendants but live a moderately comfortable life nevertheless.

The children of the second generation, commonly referred to as the “Third Generation” in Asia, often remove themselves from the preservation of wealth altogether. The third generation often grow up in an environment ill fitted for learning the difficult task of preserving the family’s wealth and status. Since the minute they were born, they are endowed a luxurious lifestyle without a care in the world. This breeds shortsightedness, leading many in the third generation to believe that money can buy happiness.

Studies also show that passing wealth on for more than three generations is indeed a challenge for many families.

(1) A survey conducted by U.S. Trust, a subsidiary of Bank of America, found that 64% of wealth creators disclosed little of their wealth to their children and 78% feel that the next generation is not financially responsible enough to handle assets they are given.

(2) A separate study conducted by Merrill Lynch found that only 15% and 2% of families in East Asia successfully transition their family businesses to the second and third generations, respectively.

(3) In 2017, CNBC reported that, “one-third of Asia’s wealth may change hands in the next five years.” It reported that many families will see their wealth reduced due to familial disputes and transition taxes.

2. Types of Wealth Creators and the problem they face

Wealth Creators often work their entire lives dedicated to their profession. By starting early and integrating their succession plan with their businesses, they can expand upon their creations and build a lasting legacy, one that incorporates their family, their employees and society at large. Wealth Creators who fail to invest adequate time and energies in creating and protecting their legacies often leave behind lasting familial disputes, shareholder disagreements, employee distress and unnecessary conflict various judicial and administrative organizations. As a Wealth Creator, you must ask yourself, “Who is my successor?” After all, the first step in familial succession is choosing a viable successor.

After meeting with many Wealth Creators, the author has come to the conclusion that the main reason they fail to act is because they fear that their actions would lead to succession inequality. Thus, they shy away from discussing or planning their legacies. Generally, Wealth Creators can be categorized into the four following categories:

- Type 1: The Staunch Believer thinks that their children and grandchildren should and will take care of themselves. They are steadfast in their beliefs and willingly choose to disregard potential disputes that may arise after their death.

- Type 2:The Procrastinator believes that their legacy is still a distant concern and fails to plan for their legacy in time.

- Type 3: The Overthinker fails to act due to their inability to make a coherent decision about his or her legacy. As the years pass by, they fail to make any progress in planning for their successors. They often regard potential successors, some as old as 60 years old, as children incapable of handling their family’s business affairs. Often times, Overthinkers also leave a multitude of different assets in a disarray and do not wish to plan the eventual transition of their wealth.

- Type 4:

If you are a potential successor and become aware of your family’s assets, you may want to consider which category your ascendants belong under. This could potentially determine your next course of action. After thinking about your ascendants, you should also think about your role in the family. Generally, the second generation falls in one of the following categories:

(1) The second generation often have less pronounced Asian values. This is especially true of descendants who have lived abroad for many years or those who started families outside of Asia. Although they are of Asian descent, they identify more closely with Western values and focus more on realizing personal goals rather than strengthening the family business and thinking on behalf of the greater family at large.

(2) The second generation may not need financial support from their families: they are often efficient workers, enjoying high socioeconomic statuses wherever they settle. Many may play an active role in their communities. Some second generation are even financially independent and live comfortably even without their families’ assets. They may not want or need wealth created by their ascendants and the responsibilities that come with that wealth. For this category of second generation, their family’s various businesses and assets could actually end up becoming a sizable burden rather than an asset.

(3) Some second generation may lack the foresight or strategic direction necessary to continue the family business. Familial disputes may arise if the second generation refuses to make decisions regarding the family business. Relationships with longstanding employees in the family business may also falter as a result of inaction or poor decision-making. The author believes that the second generation should hold themselves responsible for their family’s business, whether they choose to manage it themselves or have others manage it on their behaves.

While many Wealth Creators and their descendants want to transition their family businesses and other assets to the next generation, four major points of contention generally arise when they begin to consider succession:

(1) Transfer Costs

In many jurisdictions, there is a significant cost related to the transfer of assets from one generation to the next, especially if the assets transferred are sizable. For example, the highest intergenerational transfer tax rates in Taiwan, the United States and Japan can run as high as 20%, 40%3 and 55%, respectively. As it stands, according to various online sources, the transfer tax rate in China is slated to be implemented at 50%.

3 Excludes U.S. generation-skipping taxes (GST).(此處40%不含美國隔代移轉稅)。

(2) Succession Disputes

Succession disputes may arise as a result of a number of factors, often exacerbated by a lack of prior planning by the Wealth Creator before he or she is incapacitated. Typically, the second generation either dispute ① the assets they are entitled to or ② the various business responsibilities delegated to them.

When the first generation fails to create a comprehensive succession plan, the family business and other familial assets are often hurriedly passed on. The second generation, often unaware of the situation prior to the Wealth Creator’s death or incapacity, may be woefully unprepared to singlehandedly handle familial businesses and affairs.

The use of nominal holders of assets, commonly referred to as “nominees,” a common tactic in Asia, may only serve to further complicate the situation. If a nominee passes away or become incapacitated, the transfer of assets to the second generation may become fraught with additional expenses and challenges. It is common that disputes (either in or out of court) with nominees significantly reduce the assets passed to the second generation.

(3) Debt Disputes

While debt is instrumental in many businesses’ growth, it can also be a source of disputes during a family’s wealth transition from one generation to the next. With a larger scale comes larger profits; however, disputes regarding the legitimate owner(s) of a family’s assets and liabilities may be exacerbated by the existence of significant outstanding debts. A family’s equity can quickly be reduced if the family lacks the ability to pay either the interest expense of debt or the balloon payment upon maturity.

(4) Differences in Familial Focus and Values

The second generation often focus on different aspects of life, when compared to the Wealth Creators. While the Wealth Creator may be concerned about his or her profits and legacy, his or her descendants can focus on their time and energies on pursuing matters of interest to them rather than the profitability of the family’s businesses. Thus, without adequate and timely communication, familial values and virtues will likely not stand the test of time.

A Wealth Creator, most frequently the Founder of the family business, must place an emphasis not only on the continued growth of the family business, but also the transfer of those interests from the first generation to the second. How should the first generation constructively preserve and pass on familial businesses and assets? If the Wealth Creators’ descendants have no interest in the family’s business, should the Wealth Creator approach the situation differently? While not all Wealth Creators are founders of companies, concepts behind familial business succession are valuable for all families alike.

A family should undoubtedly include concepts of succession, financial estimation and projection, familial governance, tax and estate planning, company management and ownership transition when developing their succession strategy. To build a sustainable family business that fits with the family’s philosophy, a bespoke set of rules regulating family activity and a separate set of rules regulating corporate activity must be written down and adhered to by all family members. As additional family members take part in and contribute to the family business, establishing effective governance is essential to preventing future disputes.

Generally, there are four ways to pass on a family’s wealth when it comes to business succession:

(1) Passing the entire family business on to the second generation: Family members, generally descendants of the Wealth Creator, take control over the entire business, including its ownership and management. Participating family members are widely encouraged to participate in the company’s operations in accordance with the business’ corporate hierarchy.

(2) Passing only ownership on to the second generation: In this scenario, only the ownership of the company (generally, the shares of the company) is passed on to the second generation, while both day-to-day management and executive functions of the company largely falls on professionals hired by the Wealth Creator and / or the second generation. Ideally, the second generation will serve as members of the Board of Directors, governing the company and making the most important decisions regarding the company’s new ventures and ongoing operations.

This method of passing down the family business is especially tricky, since the professionals at the company and the second generations may find themselves increasingly at odds with one another. When not properly structured and monitored, this method often leads to the consistent decline of the family’s wealth and businesses. Thus, it is essential that those seeking to pass on only the ownership of the family business to the second generation consider professional assistance and guidance to ensure a smooth transition.

(3) Distribute ownership and management to both the second generation and professionals at the firm: In this scenario, it is imperative that the Wealth Creator clearly sets aside rules for the distribution of profits, company shares and management rights to encourage the second generation to join the business and incentivize existing and new managers to continue to perform.

(4) Liquidate the family business and pass down the proceeds of the sale to the second generation: While this method is likely the least popular among Wealth Creators, the sale of a family’s business is a big decision for any family and requires long-term planning and a thought out strategy.

When choosing between the four methods of passing on the family business, families must first consider their needs, wants, strengths and weaknesses. To ensure a successful transition, families must adjust their approach over time and reevaluate their strategy from time to time.

A family should undoubtedly include concepts of succession, financial estimation and projection, familial governance, tax and estate planning, company management and ownership transition when developing their succession strategy. To build a sustainable family business that fits with the family’s philosophy, a bespoke set of rules regulating family activity and a separate set of rules regulating corporate activity must be written down and adhered to by all family members. As additional family members take part in and contribute to the family business, establishing effective governance is essential to preventing future disputes.

Generally, there are four ways to pass on a family’s wealth when it comes to business succession:

(1) Passing the entire family business on to the second generation: Family members, generally descendants of the Wealth Creator, take control over the entire business, including its ownership and management. Participating family members are widely encouraged to participate in the company’s operations in accordance with the business’ corporate hierarchy.

(2) Passing only ownership on to the second generation: In this scenario, only the ownership of the company (generally, the shares of the company) is passed on to the second generation, while both day-to-day management and executive functions of the company largely falls on professionals hired by the Wealth Creator and / or the second generation. Ideally, the second generation will serve as members of the Board of Directors, governing the company and making the most important decisions regarding the company’s new ventures and ongoing operations.

This method of passing down the family business is especially tricky, since the professionals at the company and the second generations may find themselves increasingly at odds with one another. When not properly structured and monitored, this method often leads to the consistent decline of the family’s wealth and businesses. Thus, it is essential that those seeking to pass on only the ownership of the family business to the second generation consider professional assistance and guidance to ensure a smooth transition.

(3) Distribute ownership and management to both the second generation and professionals at the firm: In this scenario, it is imperative that the Wealth Creator clearly sets aside rules for the distribution of profits, company shares and management rights to encourage the second generation to join the business and incentivize existing and new managers to continue to perform.

(4) Liquidate the family business and pass down the proceeds of the sale to the second generation: While this method is likely the least popular among Wealth Creators, the sale of a family’s business is a big decision for any family and requires long-term planning and a thought out strategy.

When choosing between the four methods of passing on the family business, families must first consider their needs, wants, strengths and weaknesses. To ensure a successful transition, families must adjust their approach over time and reevaluate their strategy from time to time.

While understanding key concepts can help, case studies are often the best way to truly understand business succession and wealth succession. In the face of an ever-changing world, families should consider their succession strategy an increasingly important task and prioritize the creation of a sustainable plan to pass their assets on to the next generation.

1. Cases of Business Succession

Business Succession Case 1: How can companies continue their legacy and improve upon their operations as COVID-19 spreads across the world?

Background:

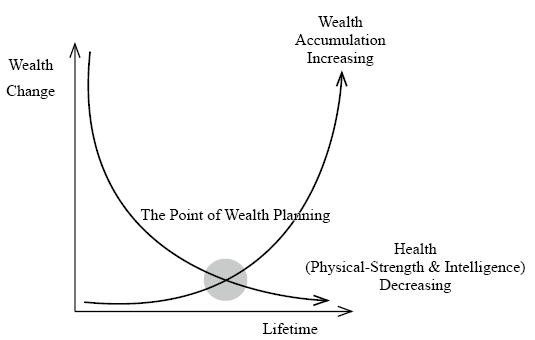

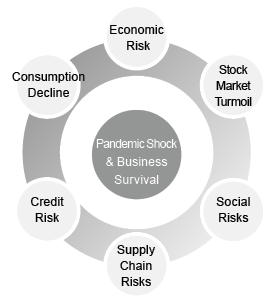

The world is now in a VUCA era (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous) with the sustained impact of COVID-19. As the Coronavirus and its variants spread globally, many businesses are suffering.

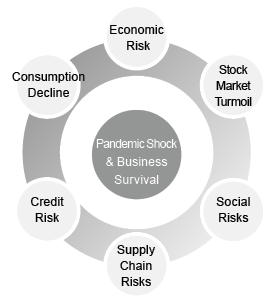

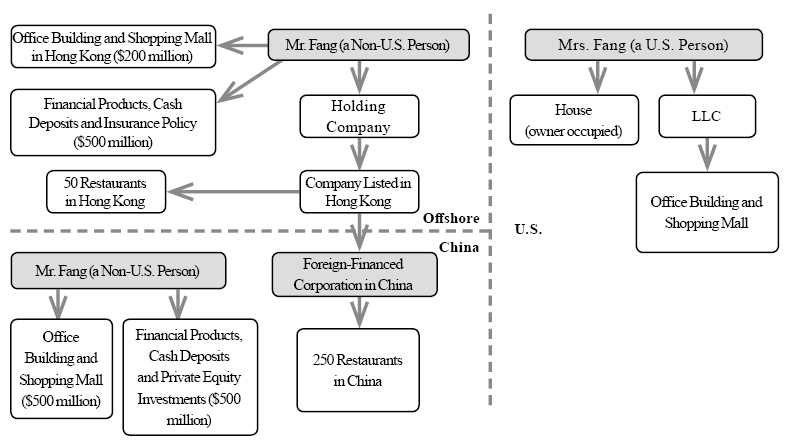

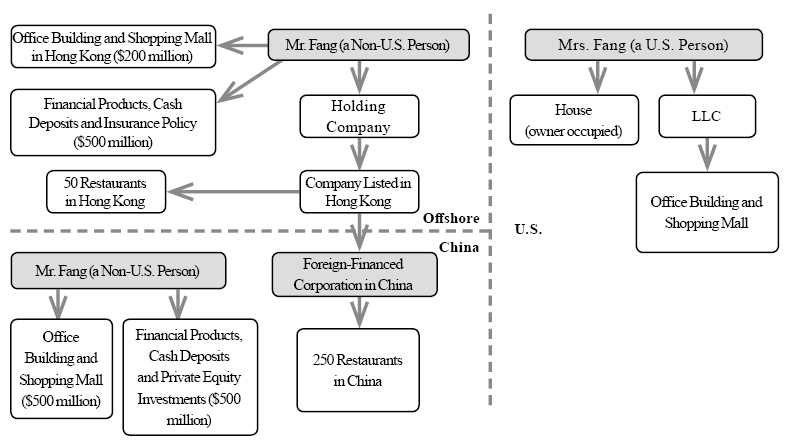

Mr. Fang, the head of a large restaurant group in Shanghai, saw that many businesses had failed in the face of the pandemic. When his family’s catering business was forcibly shut in 2020, Mr. Fang too became worried and wanted to segregate his family’s business entities from companies holding their other familial assets to prevent what happened to Chinese businessman Yueting Jia.

COVID-19 has served as a catalyst for familial wealth and business planning. Chance favors the prepared minds. Business leaders now need to know how to respond to and confront the tremendous impact of the global pandemic.

Reflections on Succession:

(1) Although Mr. Fang’s wife and children have moved to Los Angeles for many years now, the family lacked a wealth succession plan. What can Mr. Fang do to turn the COVID-19 crisis into an important planning opportunity?

(2) Companies should have business continuity plans in place for emergencies and management absences both temporary and permanent. Steps that a wealth creator can take include (A) establishing an emergency decision-making body, (B) comprehensively assessing risks, (C) clarifying emergency response mechanisms to stakeholders, (D) implementing clear divisions of labor, (E) establishing an effective, positive and proactive line of communication among the businesses stakeholders, (F) regularly evaluating the physical and psychological health of employees and (G) analyzing the nature of business segments and adapting return-to-work plans accordingly.

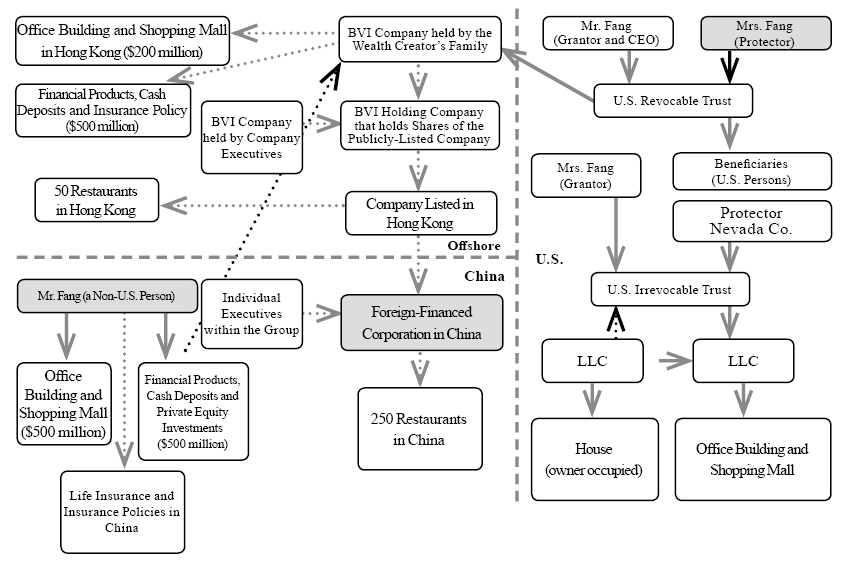

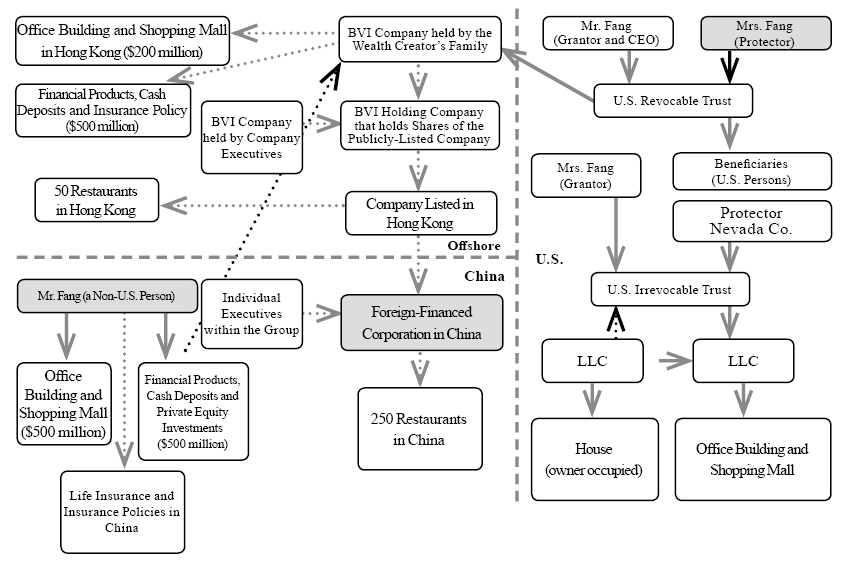

(3) When a business owner looks to restructure either his personal holdings or his business operations, he should also incorporate business succession concepts. In Mr. Fang’s case, prior to a reorganization, assets were primarily held by his company’s general manager and his wife. The reorganization restructured his family’s holdings and changed ownership of his assets from individuals to his family trust, greatly reducing future legal and tax risks.

Business Succession Framework Proposal

Succession Framework Analysis:

(1) Mr. Fang owns many assets in China. If China enacts a estate and transfer tax regime, a large proportion of Mr. Fang’s assets may be subject to taxation. To pay this tax, his descendants may have to sell off their families’ assets, potentially including shares of their publicly listed company.

(2) Since many of Mr. Fang’s family members have immigrated to the U.S. over the years, Mr. Fang should transfer a proportion of his assets into the U.S. He should do so before applying for U.S. Green Card or Citizenship for himself, if he wishes to do so. An irrevocable trust can serve as an excellent vehicle to hold his funds currently held by offshore companies in Hong Kong or Singaporean bank accounts.

(3) When Mr. Fang makes gifts to his wife and children in the U.S., it is important to consider U.S. gift and estate tax implications of any such transfer. If Mrs. Fang holds assets in the U.S., it is likely that she will be liable for estate tax if she receives additional assets from Mr. Fang over time. We recommend that Mr. Fang establish an irrevocable trust in the U.S. and transfer his assets into the U.S. irrevocable trust. This would minimize the family’s exposure to a U.S. estate tax and facilitate smooth asset transitions to the second and future generations.

(4) The management team in China should hold shares in the Foreign-Financed Corporation in China, while non-Chinese shareholders should hold shares in the BVI Company.

(5) Mr. Fang should also consider restructuring his holdings in China. Due to tight currency controls, moving assets out of China has become increasingly difficult. If the opportunity arises, Mr. Fang should consider transferring his direct or nominee-held shares of Chinese companies to offshore companies to facilitate the transfer of assets from him to his spouse or descendants. This can generally be done through direct transfers, financing events and gifts.

Business Succession Case 2: How should non-U.S. Wealth Creators transfer wealth to their descendants if their descendants are primarily U.S. persons?

Background:

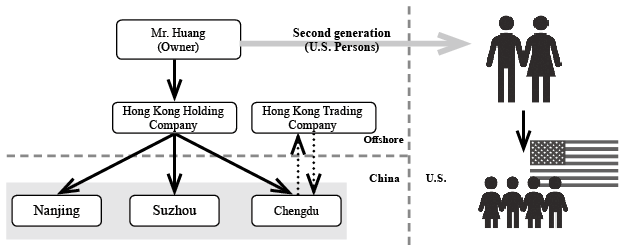

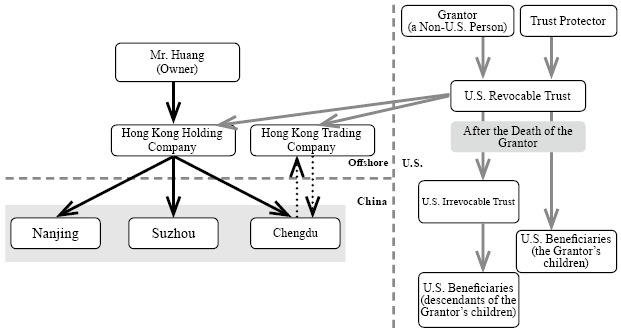

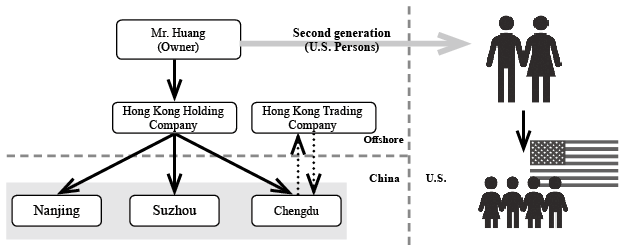

Mr. Huang owns many factories in Nanjing, Suzhou and Chengdu. His company is a major electronic parts supplier in China. Many years ago, he transferred ownership of his holding company to a Hong Kong holding company to facilitate transactions with customers and conduct research and development. Over the years, he wonders whether he should transfer ownership and / or management of his company to his U.S. children. If so, how should he balance control of the company between his children and current executives at the company before or after his death?

Specifically, he had the following questions:

(1) How should he balance the company responsibilities between his children and current executives?

(2) How should he balance ownership and the company’s profit share between his children and current executives?

(3) What is a trust? Can a family trust help him achieve his goals?

(4) If so, which trust jurisdiction should he settle his trust in? Who should he engage to draft the trust agreement or maintain the trust?

(5) How should the assets be transferred to a trust after it is established?

(6) Who should manage the trust’s assets once a trust is established?

(7) Which advisors can he trust to help him consummate his business succession plans?

Holding Company Succession Framework Proposal:

Prior to Restructuring

Analysis:

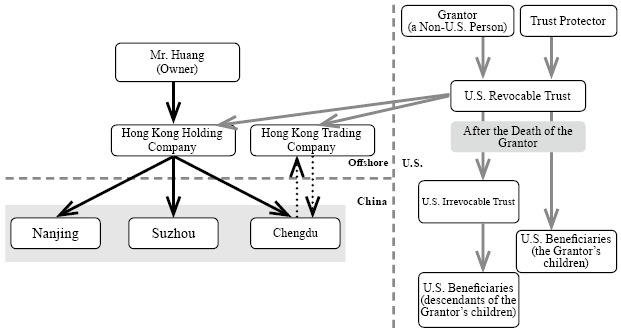

(1) An important step in business succession for Chinese Wealth Creators is transferring their ownership of their Chinese holding company from a mainland Chinese natural person or company to one or more Hong Kong and / or offshore companies. In this case, Mr. Huang’s wife and children have immigrated to the U.S., while he remains a Chinese national. It is important that Mr. Huang remains a non-U.S. person for U.S. tax and legal considerations. Once Mr. Huang’s family trust is established, he can easily gift his Hong Kong or offshore company to the trust.

(2) Usually, a trust’s domicile is chosen based on where the assets and the Beneficiaries are situated. In this scenario, all trust beneficiaries are U.S. persons. Thus, upon Mr. Huang’s death, the trust will either become a U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust or a Foreign irrevocable non-grantor trust for U.S. tax purposes. Since his descendants are U.S. persons, if the trust he settles becomes a Foreign irrevocable non-grantor trust, any trust distributions will be subject to Distributable Net Income (DNI) and Undistributed Net Income (UNI) tax rules. Income produced by foreign trusts are taxed heavily. Thus, we recommend that families with U.S. beneficiaries establish trusts treated in the U.S. as U.S. trusts rather than foreign trusts. Although foreign trusts for U.S. tax purposes are taxed heavily in the U.S., many Chinese family offices, banks and trust companies still recommend Wealth Creators foreign trusts, often settling their trusts in offshore jurisdictions, without regard for future U.S. tax consequences. Even if a trust is initially domiciled outside of the U.S., most offshore trusts can “migrate” to the U.S. or decant their assets to a U.S. trust; however, the legal and administrative hurdles to migration and decanting may pose multijurisdictional legal and tax challenges for the second generation. We recommend that Wealth Creators with U.S. beneficiaries set up U.S.-based trusts to reduce U.S. tax liability and potential legal repercussions.

(3) Mr. Huang should settle a revocable trust in the U.S. During his lifetime, the trust will be treated as a Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT) for U.S. tax purposes. All assets held outside of the U.S. are treated as directly owned by Mr. Huang (a non-resident alien, or NRA) for U.S. income tax purposes. Income earned by trust assets are neither taxable to the trust nor to the beneficiaries for the duration of Mr. Huang’s life. For U.S. income tax purposes, Mr. Huang would be liable for any income taxes; however, as a NRA in the U.S., his income tax burden generally includes only income effectively connected to the U.S. All foreign-sourced income earned by Mr. Huang is thus not taxable. When Mr. Huang passes away, the FGT converts to a U.S. non-grantor trust, relieving his descendants from the hassles of migrating an offshore trust to the U.S.

(4) By settling a U.S. Revocable Trust, Mr. Huang does not cede control of his assets during his lifetime. He is also able to separate management of his company from ownership of his company. By transferring his shares into a U.S. revocable trust, he will generally not be deemed the owner of the company’s shares outside of the U.S.; however, he is still able to control any corporate decision-making. This could potentially buy him additional time to train qualified managers to take over the business, while knowing that shares of his company will be passed on to his descendants upon his death.

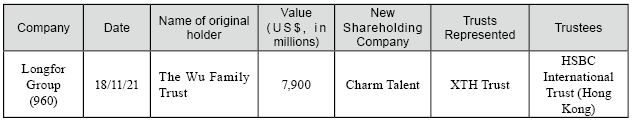

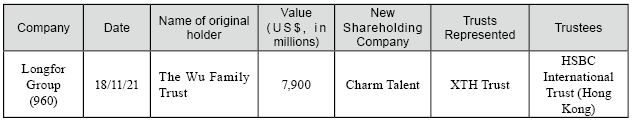

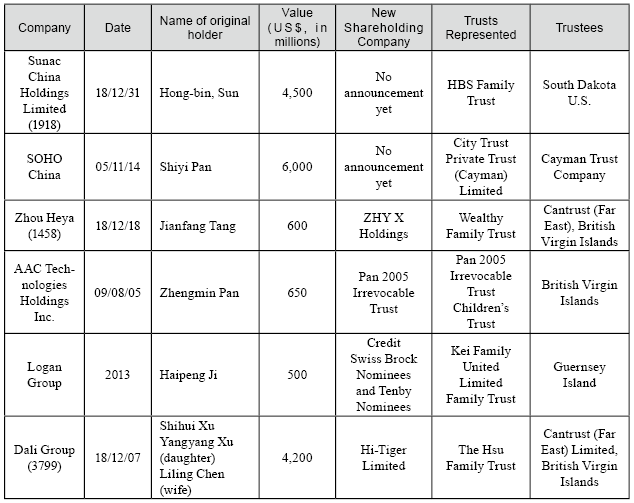

Business Succession Case 3: Pre-IPO Succession Planning (Hong Kong, U.S.) and the impact of Common Reporting Standards (CRS)

Background:

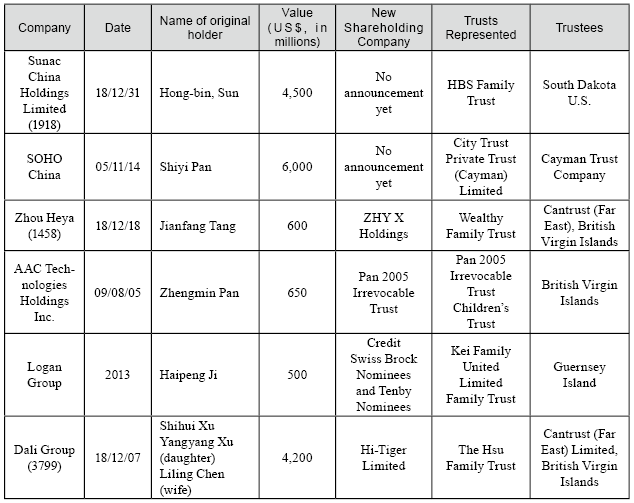

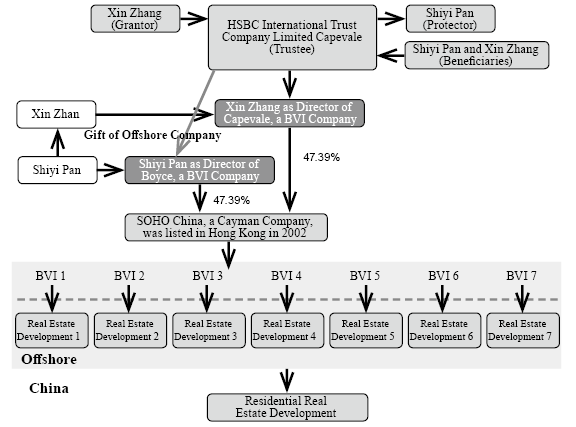

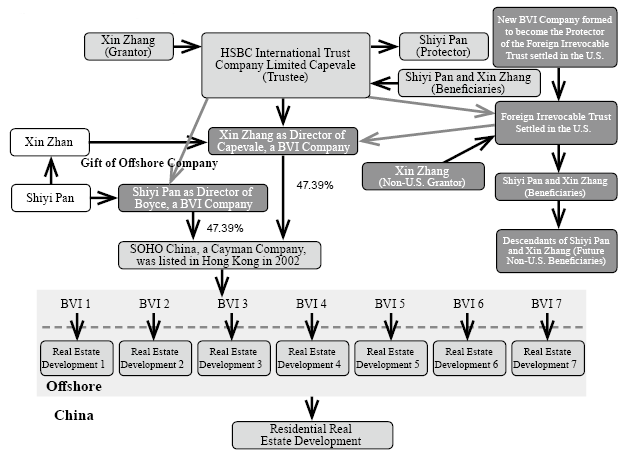

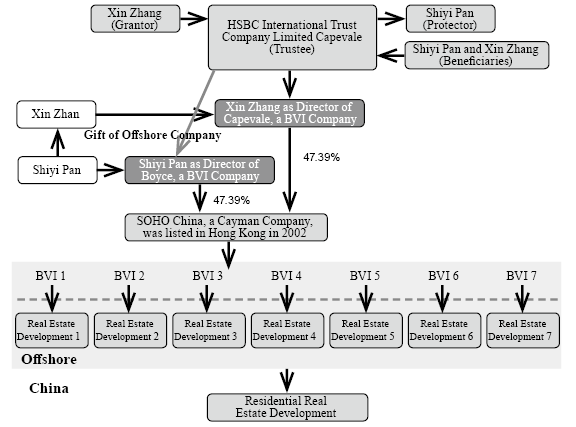

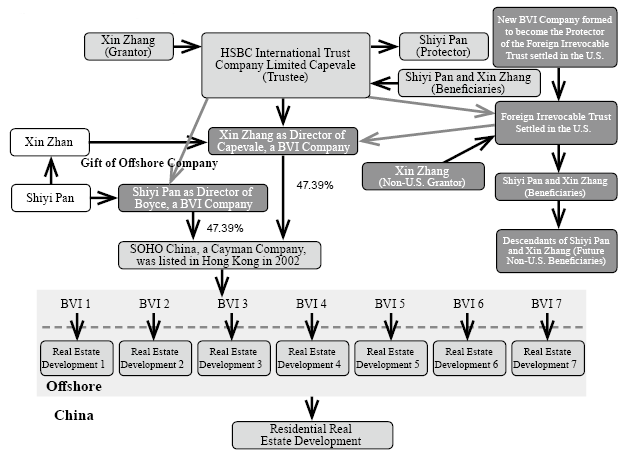

Shiyi Pan and Zhang Xin are married entrepreneurs residing in China. Previously, they appointed HSBC International Trust Company Limited (Capevale) as Trustee of their family trust. They hoped that HSBC would help them internationalize their assets and provide them with an appropriate holding structure prior to their company’s Initial Public Offering (IPO) in Hong Kong. However, in 2018, countries committed to participating in the Common Reporting Standards (CRS) began to exchange financial information. This had a significant effect on the Pan family’s succession plans. Mr. Pan worried that the information exchange would put him and his family at significant tax risk. As Chinese citizens, Shiyi and Zhang became increasingly concerned that their assets would soon be subject to income, estate and gift taxes and that they would be subject to potential interest and / or penalties.

Succession Reflections:

(1) Prior to going public, Chinese companies often wish to source capital outside of China. Owners of and investors in Pre-IPO companies must consider how they can eventually exit their position. This often entails directly or indirectly transferring their nominal ownership of a company’s shares to offshore entities. These offshore entities often consist of offshore trusts, offshore companies, special purpose trusts and other entities.

Owners and investors frequently underestimate the importance of transferring their shares to an offshore entity. Those who move their shares offshore enjoy protection against business operation risks, estate taxes, other transfer taxes and potentially protection against potential creditors, including ex-spouses.

When settling an offshore trust, the Wealth Creator can transfer a portion or all of his shares into the trust. If the shares are currently held by a nominee, the nominee could settle the offshore trust, with the Wealth Creator acting as the holder of all substantial powers and decisions in the trust (often referred to as the Trust Protector). Offshore trusts are frequently settled with the intention of having an Offshore Trustee serve as the nominal owner of the assets deposited, disregarding the powers granted to Protectors and Beneficiaries.

In the last decade, as one would expect, Wealth Creators desired more and more control over trust assets. For this reason, professionals from around the world began recommending the use of Private Trust Companies (PTCs). These new structures allowed Wealth Creators to assign themselves, their family members and / or their most trusted advisors important roles within the PTC. Thus, the demand for offshore trusts and PTCs grew to levels never seen before. Many professionals now market structures that centralized power and grant those powers to the Wealth Creator, advertising it as indispensable legal frameworks for Pre-IPO investors and shareholders.

(2) Founders of Pre-IPO companies and the company’s executives often hold the highest stake prior to a liquidation event (an IPO or an acquisition). Many shareholders of Pre-IPO companies will set up a Directed Trust. The Directed Trust document will expressly provide that the Beneficiaries will be selected by the Trust Protector and that any distributions would have to be approved by the Trust’s Distribution Advisor (usually, the same person or entity as the Trust Protector). In these structures, Trustees are only responsible for adhering to the rules set forth in the trust agreement. Common jurisdictions for these trusts include the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Guernsey and Jersey.

After the trust is formally established, shareholders transfer shares to the trust. Legally, the owner of these shares will henceforth become the Trustee Company. Thus, during the IPO, the Trustee, rather than an individual, is disclosed as shareholder. Despite of this, the trust’s Grantor often retains full control of the trust assets (investment, management and distribution), with the Trustee serving only in an administrative capacity.

(3) At a first glance, offshore trusts seem to be a silver bullet for high net worth individuals around the world. However, when taking a deeper dive, we often find that offshore trusts are not able to withstand legal and political scrutiny.

In 2016, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) revealed the Panama Papers. Mossack Fonseca & Co., a Panamanian law firm, released 11.5 million confidential client files, revealing their wealthy clients from all around the world. Many were using tax havens to hide wealth, evade taxes and launder money.

In 2017, the ICIJ revealed even more documents through the publication of the “Paradise Papers.” The leak contained 13.4 million documents drafted between the 1950s and 2016. The leak included information from Appleby, a well-known offshore trustee, and Estera, a professional services provider for high net worth clients.

Succession Framework Proposal:

Succession Framework Analysis:

(1) Advisors working with clients who wish to create Foreign Trusts settled in the U.S. as Pre-IPO trusts should evaluate the following:

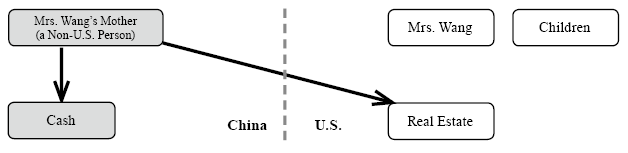

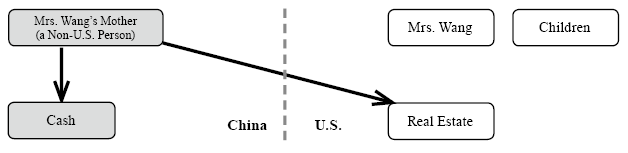

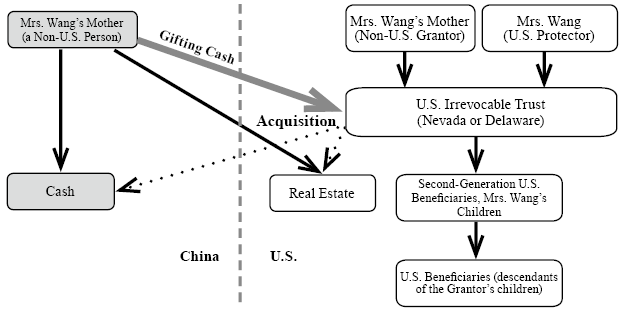

Wealth Succession Case 1: Purchasing U.S. Real Property using a Foreigner Nominee

Background:

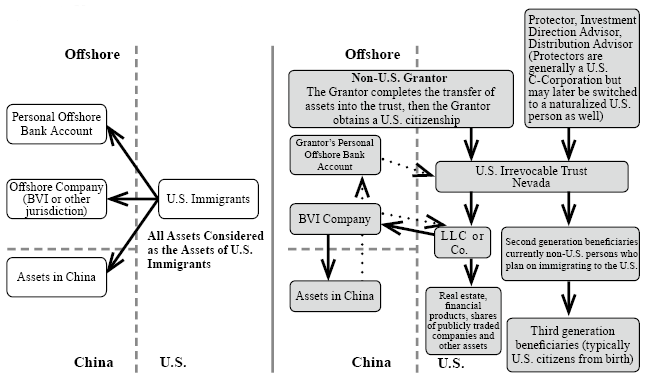

Mrs. Wang is a longstanding executive at a construction company based in Shanghai. Over the years, she has accumulated wealth both in mainland China and overseas. Like many Wealth Creators, Mrs. Wang wished for her descendants to move to the United States and settle there permanently. Through many of her friends, she heard that the U.S. levies a hefty estate tax on the wealthy. To reduce future U.S. estate taxes, she transferred funds held offshore to her mother, a Chinese citizen, before she became a U.S. person and had her mother purchase a number of rental properties in the U.S.

Two years later, a close friend introduced her to a U.S. accountant, who informed her that U.S. estate taxes are levied not only on U.S. persons, but also foreigners with certain assets in the U.S. Furthermore, the gift and estate tax exemption for foreigners was a paltry $60,000 and any taxable estate in excess could be subject to a tax of up to 40% or more of the net value of assets held. Mrs. Wang was in disbelief and now wondered whether she would be able to revise her tax structure.

Reflections on Succession:

(1) The use of nominees for asset holding structures is extremely widespread in China. High net worth individuals in China are often accustomed to holding assets under the names of others, despite the significant risks that may arise as a result of those structures. While the legality of nominee usage is generally not questioned in China, individuals who use nominees to hold assets outside of China may face unexpected challenges. As such, if the nominee is able and willing to claim the assets as their own, it may pose a significant legal obstacle in the U.S. and even in offshore jurisdictions if proper preventative measures are not in place. In addition, if the nominee’s health is in question and the nominee has descendants or family members, there may also be a dispute regarding whether assets held by the nominee is includible in the nominee’s estate for tax or legal purposes, as the nominee’s family may or may not be willing to cooperate or even be aware of the arrangements that previously took place.

(2) When moving assets to the U.S., Wealth Creators have to be able to explain their sources of wealth. Once the U.S. gets jurisdiction over assets, the U.S. Treasury Department or Internal Revenue Service (IRS) may question the sources of funds and / or investigate foreign income that may or may not have been required to be previously disclosed.

(3) New immigrants from China often wish to quickly open bank accounts and purchase U.S. real estate under the names of their foreign relatives, friends or associates. They may see this as an opportunity to invest in the U.S., while avoiding their U.S. tax and disclosure obligations; however, many do not learn of the U.S. estate tax for foreigners until it is too late.

Succession Framework Proposal:

Succession Framework Analysis:

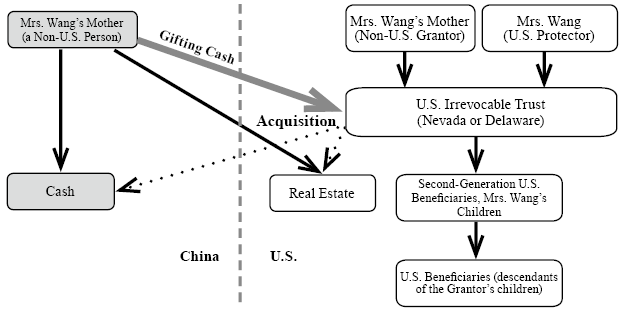

(1) Since Mrs. Wang purchased property under her mother’s name, she must now unwind her prior transactions in a tax efficient manner. Typically, in these situations, we would recommend that Mrs. Wang’s mother establish a U.S. Irrevocable Non-Grantor Trust. Mrs. Wang, a U.S. person, can serve as the Trust Protector of this trust and her children can be selected as Beneficiaries of the trust.

(2) Once set up, the Trust can establish U.S. Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) and open U.S. bank checking accounts held by those LLCs.

(3) Mrs. Wang hires a real estate appraiser and appraises the assets currently held by Mrs. Wang’s mother.

(4) Mrs. Wang’s mother gifts funds from her personal bank account in Hong Kong or Singapore into a bank account set up by the U.S. LLC (held 100% by the U.S. Trust).

(5) The U.S. LLC then purchases the U.S. real estate from Mrs. Wang’s mother. Once Mrs. Wang’s mother receives the proceeds from the sale, she can wire those funds to her personal bank account in Hong Kong or Singapore. Then, she can then wire those funds back to the U.S. LLC and use funds held by the U.S. LLC to purchase additional real estate from herself. This process can be repeated until the real estate is all held by the U.S. Trust. Assets held by the Trust are generally not subject to U.S. estate tax.

Wealth Succession Case 2: What happens if an offshore trust is not legally recognized in a jurisdiction? What is an illusory trust?

Background:

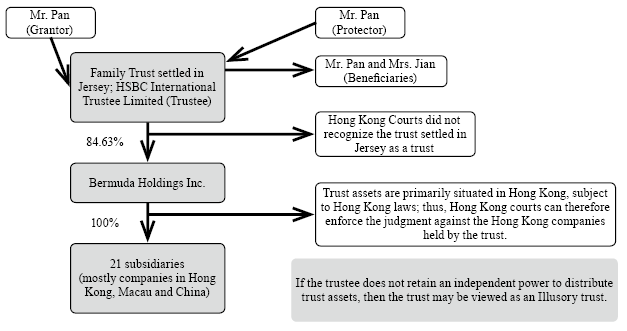

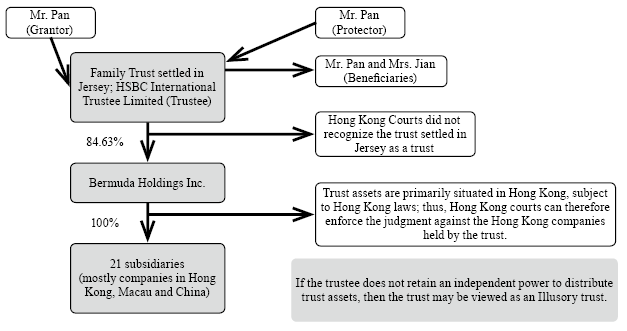

Wealth Creators from Hong Kong have used offshore trusts to protect their assets for many decades now. Yuetao Pan, the founder of Analogue Holdings Limited, settled an Irrevocable Jersey Trust in July 1995. He served as the Trust’s Grantor, the Trust Protector and one of the Trust’s Beneficiaries. HSBC International Trust Company Limited was appointed as Trustee. After the Trust was settled, he gifted 85% of Analogue Holdings Limited to his trust. In 2014, the Hong Kong Supreme Court ruled that it did not consider the Trust to be an independent entity; therefore, Yuetao’s wife now had lawful claims over half of the trust’s assets.

Reflections on Succession:

This ruling came as a shock to many Wealth Creators, since they previously believed that offshore trusts would legally be construed as its own independent entity and thus could protect them from disputes with creditors.

(1) Over the last decade, offshore trusts have separated into three separate types of structures. (A) A private bank or wealth manager creates a trust for the primary purpose of investing the clients’ assets. (B) A client seeks out a professional Trust Company and settles a trust for the primary purpose of asset protection or succession planning. (C) A client seeks out attorneys and trust companies for assistance with settling a Private Trust Company (PTC). Generally, a PTC may have asset protection and succession planning functions but also may serve as a vehicle for wealth managers to manage the clients’ assets.

When settling an offshore trust, the Wealth Creator should evaluate pros and cons of each trust jurisdiction. Typically, if there is a dispute, any complaints would be filed in the jurisdiction that the Trustee Company is situated and not where the assets held by the trust are situated. In Structure A, described above, private bankers and wealth managers attempt to recommend trusts that minimize the Grantor’s tax liability and maximize the Grantor’s retained powers. This may lead to an arrangement in which the trustee has limited to no power to manage trust assets and the Grantor retains so much power that a competent court could rule that no such trust ever existed. These trusts are often referred to as “Illusory Trusts.”

(2) While many jurisdictions offer Trust Grantors flexibility in an attempt to win their business, offshore trusts, generally settled on certain islands or territories, often provide the maximum amount of flexibility to trust attorneys, especially when compared to U.S. trusts. For many years, this was seen as a boon for asset protection attorneys and professionals; however, as clearly illustrated in Yuetao’s case, a high degree of control may lead other jurisdictions to disregard the trust structure in its entirety. The Hong Kong Supreme Court ruled that the trust previously settled was not a trust at all, since the Grantor was simultaneously the main controller (the Trust Protector) and a beneficiary. The risk of a trust being recognized as an “illusory trust” is increasing, as more and more competent jurisdictions realize that an offshore trust is only a trust in name and not in substance.

Succession Framework Proposal:

Succession Framework Analysis:

While offshore trusts have long been a prime candidate for wealth families, balancing the need for control with the asset protection qualities of a trust is important to keep in mind. If the Grantor of a trust retains many powers over the trust, courts may view the trust skeptically and deny that the trust ever existed. This could potentially cause assets to be seized by creditors and / or tax collectors. The following steps are crucial for determining whether a trust is able to serve its function and protect assets from potential creditors:

(1) When reviewing a trust agreement, advisors typically focus on the Grantor’s intent. Typically, trusts are settled either to protect the Grantor’s assets or reduce tax-related risks. Other important aspects to consider include the current and future tax residences of the Grantor and / or the trust’s beneficiaries.

(2) When analyzing a trust agreement, advisors also focus on the trust’s independence. A Grantor should generally not also have powers to control the trust’s assets. If the trust agreement provides for a Trust Protector, generally the fiduciary in charge of the operations and maintenance of the trust, the Grantor and the trust’s beneficiaries should not also serve as the Trust Protector to protect the trust from becoming an Illusory Trust.

(3) When drafting a structure that includes a trust, advisors should consider potential gift and estate tax consequences for the Grantor, the beneficiaries and the trust itself.

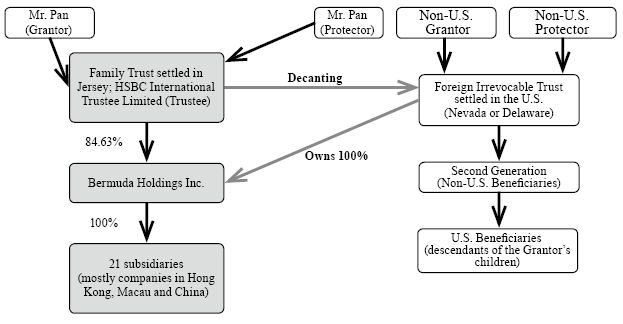

(4) Even if the existing trust does not have issues relating to independence or taxes, we advise Trust Protectors of offshore trusts to consider changing the trust’s jurisdiction to the United States. While the process may seem daunting, often requiring the assistance of U.S. and non-U.S. attorneys and accountants, the stable legal jurisdiction and consistent set of protective trust laws is almost always worth the effort.

(5) U.S. trusts (including Foreign Trusts settled in the U.S.) are typically drafted and / or reviewed by attorneys in the state that the trust is settled. Typically, those attorneys also give an opinion regarding the independence of the trust and a separate opinion regarding potential U.S. tax consequences.

Wealth Succession Case 3: Pre-Immigration Planning

Background:

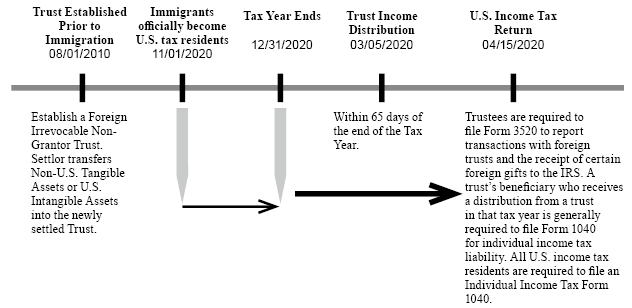

Mr. Jiang and Mrs. Jiang, a married couple residing in China, finally received their U.S. Permanent Resident Cards (Green Cards) after spending more than a decade waiting. Since they were not sure that they were going to ever receive their green cards, they did not plan for the tax consequences of their U.S. tax residency. Once they came to the U.S., they consulted with a trusted U.S. CPA, who informed them that their assets would now be subjected to U.S. gift and estate taxes, much to their disbelief.

Reflections on Succession:

(1) For many years, Hong Kong, Australia and Canada have increasingly tightened their immigration policies. The enactment of EB-5 in the U.S. came as a relief to many Chinese families seeking to permanently relocate their families. Tax advisors often advise that Wealth Creators retain their original citizenships and residency, while their spouse applies for a Green Card; however, this is easier said than done. Many Chinese nationals believe that a married couple should stay together indefinitely and never separate; however, from a tax perspective, this way of thinking may come at a significantly higher cost than most previously expect.

(2) Once a foreign national obtains a Green Card and becomes a U.S. tax resident, he or she is liable for not only U.S. income taxes on his or her worldwide income, but also liable for disclosing his or her offshore assets in accordance with various U.S. laws and regulations. Many wonder whether there is a way to attain U.S. permanent residency, without the enormous tax and disclosure responsibilities that come with it. For those that created their wealth outside of the U.S., is there a path to U.S. citizenship without the payment of considerable income, estate and gift taxes?

Succession Framework Proposal:

Succession Framework Analysis:

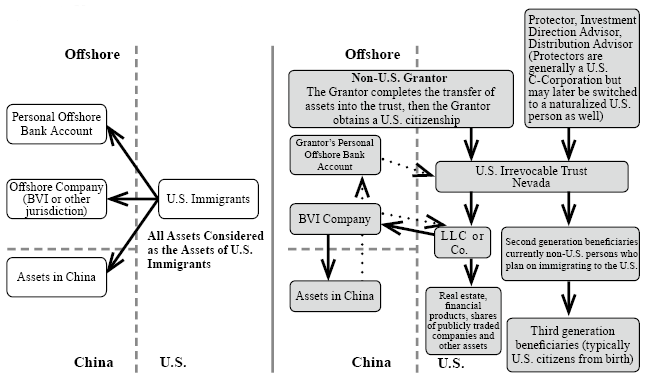

(1) For wealthy families that plan on immigrating to the U.S., investing in U.S. properties will seem to be a natural step to take; however, many Wealth Creators fail to accurately account for the tax ramifications of such investments. Prior to becoming U.S. tax residents, Wealth Creators should consult with experienced tax and legal advisors and discuss the options available to achieve wealth succession and tax minimization.

(2) Families immigrating to the U.S. with wealth abroad inevitably want to transfer a portion or all of their assets from their home country (or the country they hold their wealth in) to the U.S. Generally, we recommend that families bringing in excess of $1 million seek professional assistance and consider trust structures to minimize current and future legal and tax liabilities.

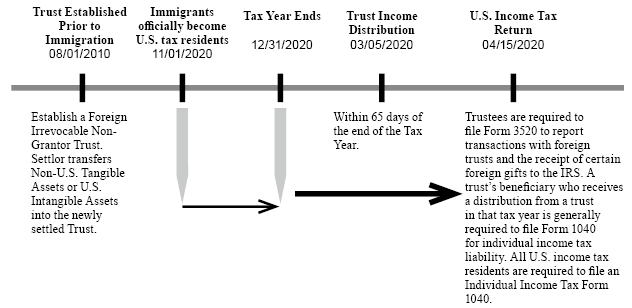

(3) Prior to becoming a U.S. tax resident, Wealth Creators with significant wealth should create an irrevocable U.S. non-grantor trust. If the Wealth Creator immigrates without doing so, his assets will be subject to a 40% estate tax over the gift and estate tax exemption amount, regardless of whether those assets were created pre- or post-immigration. If the Wealth Creator has grandchildren, he or she may also face additional taxation in the form of a U.S. Generation-Skipping Tax (GST).

(4) When settling a U.S. trust, the Grantor must assign individuals and / or corporations or LLCs to certain roles within the trust. Typically, in a U.S. trust, there will be four primary roles: the Grantor, the Trustee, the Protector and the Beneficiary (or Beneficiaries). The Grantor, typically the Wealth Creator, funds the trust with its principal. The Trustee handles the administrative and secretarial functions of the trust. Generally, it is preferred that the Trustee be a U.S. Trust Company (annual fees are approximately $5,000 ~ $10,000 and are generally a flat annual fee); however, one can also employ an individual to serve as Trustee. The Protector is the primary holder of power, the manager of the trust’s investments and distributions and may, if the trust agreement allows for it, add or remove beneficiaries. Finally, the trust’s beneficiaries receive income or principal distributions from the Trust.

(5) Pre-immigration planning is key for Wealth Creators seeking to immigrate to the U.S. Generally speaking, from a tax perspective, it is in the interest of Wealth Creators to transfer their assets to trusted foreigners (generally the Wealth Creator’s ascendants) prior to immigration, especially if there is no transfer tax concerns in the Wealth Creator’s home jurisdiction. Once the Wealth Creator immigrates to the United States, he or she will have an obligation to disclose their direct offshore holdings and be taxed on his or her global income. If the Wealth Creator (or his descendants) need assets to be transferred to the U.S. after the Wealth Creator immigrates, the trusted foreigner can always gift assets back free of U.S. transfer taxes; however, it is recommended that direct transfers be limited to a small gift and that larger gifts (gifts > US$1 million) are made using U.S. irrevocable trusts or Foreign Trusts settled in the U.S.

(6) In addition, if an offshore trust has been established by Mr. Jiang before he obtains green card, he will be required to pay U.S. individual income tax based on the income generated from the trust for five years once he obtains green card. Above is based on Section 679(a)(4)(A), please refer to Appendices, Section E for details. In addition to individual income tax reporting Mr. Jiang must file Form 3520 with the “Foreign Grantor Trust Owner Statement” received from the trustee attached to report ownership of the foreign trust each year since he is the U.S. owner of the foreign grantor trust. The U.S. tax declaration involved in this is quite complicated, and the penalties for failing to file on time, failing to disclose all information, or revealing wrong information are quite heavy. As a result, readers who intend to obtain U.S. citizenship in the future should consider the impact of setting up an offshore trust.

1. Cases of Business Succession

Business Succession Case 1: How can companies continue their legacy and improve upon their operations as COVID-19 spreads across the world?

Background:

The world is now in a VUCA era (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous) with the sustained impact of COVID-19. As the Coronavirus and its variants spread globally, many businesses are suffering.

Mr. Fang, the head of a large restaurant group in Shanghai, saw that many businesses had failed in the face of the pandemic. When his family’s catering business was forcibly shut in 2020, Mr. Fang too became worried and wanted to segregate his family’s business entities from companies holding their other familial assets to prevent what happened to Chinese businessman Yueting Jia.

COVID-19 has served as a catalyst for familial wealth and business planning. Chance favors the prepared minds. Business leaders now need to know how to respond to and confront the tremendous impact of the global pandemic.

Reflections on Succession:

(1) Although Mr. Fang’s wife and children have moved to Los Angeles for many years now, the family lacked a wealth succession plan. What can Mr. Fang do to turn the COVID-19 crisis into an important planning opportunity?

(2) Companies should have business continuity plans in place for emergencies and management absences both temporary and permanent. Steps that a wealth creator can take include (A) establishing an emergency decision-making body, (B) comprehensively assessing risks, (C) clarifying emergency response mechanisms to stakeholders, (D) implementing clear divisions of labor, (E) establishing an effective, positive and proactive line of communication among the businesses stakeholders, (F) regularly evaluating the physical and psychological health of employees and (G) analyzing the nature of business segments and adapting return-to-work plans accordingly.

(3) When a business owner looks to restructure either his personal holdings or his business operations, he should also incorporate business succession concepts. In Mr. Fang’s case, prior to a reorganization, assets were primarily held by his company’s general manager and his wife. The reorganization restructured his family’s holdings and changed ownership of his assets from individuals to his family trust, greatly reducing future legal and tax risks.

Business Succession Framework Proposal

- Prior to Restructuring ($ in RMB)

- After Restructuring

Succession Framework Analysis:

(1) Mr. Fang owns many assets in China. If China enacts a estate and transfer tax regime, a large proportion of Mr. Fang’s assets may be subject to taxation. To pay this tax, his descendants may have to sell off their families’ assets, potentially including shares of their publicly listed company.

(2) Since many of Mr. Fang’s family members have immigrated to the U.S. over the years, Mr. Fang should transfer a proportion of his assets into the U.S. He should do so before applying for U.S. Green Card or Citizenship for himself, if he wishes to do so. An irrevocable trust can serve as an excellent vehicle to hold his funds currently held by offshore companies in Hong Kong or Singaporean bank accounts.

(3) When Mr. Fang makes gifts to his wife and children in the U.S., it is important to consider U.S. gift and estate tax implications of any such transfer. If Mrs. Fang holds assets in the U.S., it is likely that she will be liable for estate tax if she receives additional assets from Mr. Fang over time. We recommend that Mr. Fang establish an irrevocable trust in the U.S. and transfer his assets into the U.S. irrevocable trust. This would minimize the family’s exposure to a U.S. estate tax and facilitate smooth asset transitions to the second and future generations.

(4) The management team in China should hold shares in the Foreign-Financed Corporation in China, while non-Chinese shareholders should hold shares in the BVI Company.

(5) Mr. Fang should also consider restructuring his holdings in China. Due to tight currency controls, moving assets out of China has become increasingly difficult. If the opportunity arises, Mr. Fang should consider transferring his direct or nominee-held shares of Chinese companies to offshore companies to facilitate the transfer of assets from him to his spouse or descendants. This can generally be done through direct transfers, financing events and gifts.

Business Succession Case 2: How should non-U.S. Wealth Creators transfer wealth to their descendants if their descendants are primarily U.S. persons?

Background:

Mr. Huang owns many factories in Nanjing, Suzhou and Chengdu. His company is a major electronic parts supplier in China. Many years ago, he transferred ownership of his holding company to a Hong Kong holding company to facilitate transactions with customers and conduct research and development. Over the years, he wonders whether he should transfer ownership and / or management of his company to his U.S. children. If so, how should he balance control of the company between his children and current executives at the company before or after his death?

Specifically, he had the following questions:

(1) How should he balance the company responsibilities between his children and current executives?

(2) How should he balance ownership and the company’s profit share between his children and current executives?

(3) What is a trust? Can a family trust help him achieve his goals?

(4) If so, which trust jurisdiction should he settle his trust in? Who should he engage to draft the trust agreement or maintain the trust?

(5) How should the assets be transferred to a trust after it is established?

(6) Who should manage the trust’s assets once a trust is established?

(7) Which advisors can he trust to help him consummate his business succession plans?

Holding Company Succession Framework Proposal:

Prior to Restructuring

- After Restructuring

Analysis:

(1) An important step in business succession for Chinese Wealth Creators is transferring their ownership of their Chinese holding company from a mainland Chinese natural person or company to one or more Hong Kong and / or offshore companies. In this case, Mr. Huang’s wife and children have immigrated to the U.S., while he remains a Chinese national. It is important that Mr. Huang remains a non-U.S. person for U.S. tax and legal considerations. Once Mr. Huang’s family trust is established, he can easily gift his Hong Kong or offshore company to the trust.

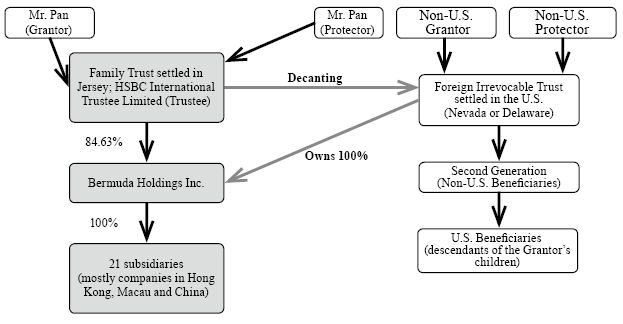

(2) Usually, a trust’s domicile is chosen based on where the assets and the Beneficiaries are situated. In this scenario, all trust beneficiaries are U.S. persons. Thus, upon Mr. Huang’s death, the trust will either become a U.S. irrevocable non-grantor trust or a Foreign irrevocable non-grantor trust for U.S. tax purposes. Since his descendants are U.S. persons, if the trust he settles becomes a Foreign irrevocable non-grantor trust, any trust distributions will be subject to Distributable Net Income (DNI) and Undistributed Net Income (UNI) tax rules. Income produced by foreign trusts are taxed heavily. Thus, we recommend that families with U.S. beneficiaries establish trusts treated in the U.S. as U.S. trusts rather than foreign trusts. Although foreign trusts for U.S. tax purposes are taxed heavily in the U.S., many Chinese family offices, banks and trust companies still recommend Wealth Creators foreign trusts, often settling their trusts in offshore jurisdictions, without regard for future U.S. tax consequences. Even if a trust is initially domiciled outside of the U.S., most offshore trusts can “migrate” to the U.S. or decant their assets to a U.S. trust; however, the legal and administrative hurdles to migration and decanting may pose multijurisdictional legal and tax challenges for the second generation. We recommend that Wealth Creators with U.S. beneficiaries set up U.S.-based trusts to reduce U.S. tax liability and potential legal repercussions.

(3) Mr. Huang should settle a revocable trust in the U.S. During his lifetime, the trust will be treated as a Foreign Grantor Trust (FGT) for U.S. tax purposes. All assets held outside of the U.S. are treated as directly owned by Mr. Huang (a non-resident alien, or NRA) for U.S. income tax purposes. Income earned by trust assets are neither taxable to the trust nor to the beneficiaries for the duration of Mr. Huang’s life. For U.S. income tax purposes, Mr. Huang would be liable for any income taxes; however, as a NRA in the U.S., his income tax burden generally includes only income effectively connected to the U.S. All foreign-sourced income earned by Mr. Huang is thus not taxable. When Mr. Huang passes away, the FGT converts to a U.S. non-grantor trust, relieving his descendants from the hassles of migrating an offshore trust to the U.S.

(4) By settling a U.S. Revocable Trust, Mr. Huang does not cede control of his assets during his lifetime. He is also able to separate management of his company from ownership of his company. By transferring his shares into a U.S. revocable trust, he will generally not be deemed the owner of the company’s shares outside of the U.S.; however, he is still able to control any corporate decision-making. This could potentially buy him additional time to train qualified managers to take over the business, while knowing that shares of his company will be passed on to his descendants upon his death.

Business Succession Case 3: Pre-IPO Succession Planning (Hong Kong, U.S.) and the impact of Common Reporting Standards (CRS)

Background:

Shiyi Pan and Zhang Xin are married entrepreneurs residing in China. Previously, they appointed HSBC International Trust Company Limited (Capevale) as Trustee of their family trust. They hoped that HSBC would help them internationalize their assets and provide them with an appropriate holding structure prior to their company’s Initial Public Offering (IPO) in Hong Kong. However, in 2018, countries committed to participating in the Common Reporting Standards (CRS) began to exchange financial information. This had a significant effect on the Pan family’s succession plans. Mr. Pan worried that the information exchange would put him and his family at significant tax risk. As Chinese citizens, Shiyi and Zhang became increasingly concerned that their assets would soon be subject to income, estate and gift taxes and that they would be subject to potential interest and / or penalties.

Succession Reflections:

(1) Prior to going public, Chinese companies often wish to source capital outside of China. Owners of and investors in Pre-IPO companies must consider how they can eventually exit their position. This often entails directly or indirectly transferring their nominal ownership of a company’s shares to offshore entities. These offshore entities often consist of offshore trusts, offshore companies, special purpose trusts and other entities.

Owners and investors frequently underestimate the importance of transferring their shares to an offshore entity. Those who move their shares offshore enjoy protection against business operation risks, estate taxes, other transfer taxes and potentially protection against potential creditors, including ex-spouses.

When settling an offshore trust, the Wealth Creator can transfer a portion or all of his shares into the trust. If the shares are currently held by a nominee, the nominee could settle the offshore trust, with the Wealth Creator acting as the holder of all substantial powers and decisions in the trust (often referred to as the Trust Protector). Offshore trusts are frequently settled with the intention of having an Offshore Trustee serve as the nominal owner of the assets deposited, disregarding the powers granted to Protectors and Beneficiaries.

In the last decade, as one would expect, Wealth Creators desired more and more control over trust assets. For this reason, professionals from around the world began recommending the use of Private Trust Companies (PTCs). These new structures allowed Wealth Creators to assign themselves, their family members and / or their most trusted advisors important roles within the PTC. Thus, the demand for offshore trusts and PTCs grew to levels never seen before. Many professionals now market structures that centralized power and grant those powers to the Wealth Creator, advertising it as indispensable legal frameworks for Pre-IPO investors and shareholders.

(2) Founders of Pre-IPO companies and the company’s executives often hold the highest stake prior to a liquidation event (an IPO or an acquisition). Many shareholders of Pre-IPO companies will set up a Directed Trust. The Directed Trust document will expressly provide that the Beneficiaries will be selected by the Trust Protector and that any distributions would have to be approved by the Trust’s Distribution Advisor (usually, the same person or entity as the Trust Protector). In these structures, Trustees are only responsible for adhering to the rules set forth in the trust agreement. Common jurisdictions for these trusts include the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Guernsey and Jersey.

After the trust is formally established, shareholders transfer shares to the trust. Legally, the owner of these shares will henceforth become the Trustee Company. Thus, during the IPO, the Trustee, rather than an individual, is disclosed as shareholder. Despite of this, the trust’s Grantor often retains full control of the trust assets (investment, management and distribution), with the Trustee serving only in an administrative capacity.

(3) At a first glance, offshore trusts seem to be a silver bullet for high net worth individuals around the world. However, when taking a deeper dive, we often find that offshore trusts are not able to withstand legal and political scrutiny.

In 2016, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) revealed the Panama Papers. Mossack Fonseca & Co., a Panamanian law firm, released 11.5 million confidential client files, revealing their wealthy clients from all around the world. Many were using tax havens to hide wealth, evade taxes and launder money.

In 2017, the ICIJ revealed even more documents through the publication of the “Paradise Papers.” The leak contained 13.4 million documents drafted between the 1950s and 2016. The leak included information from Appleby, a well-known offshore trustee, and Estera, a professional services provider for high net worth clients.

Succession Framework Proposal:

- Before Restructuring: Shiyi Pan, Xin Zhang and their offshore trust

- After Restructuring: Shiyi, Pan and Xin Zhang and their offshore family trust

Succession Framework Analysis:

(1) Advisors working with clients who wish to create Foreign Trusts settled in the U.S. as Pre-IPO trusts should evaluate the following:

- Does the trust’s Grantor have U.S. citizenship?

- Do any of the trust’s Beneficiaries have U.S. citizenships?

- Do any of the trust’s Protectors have U.S. citizenships?

- Which powers does the Trust Protector have, in accordance with the trust agreement? Who has the authority to replace the Trust Protector?

- Which powers does the Trustee or Trust Company have, in accordance with the trust agreement?

- Can a Trustee be removed or replaced, in accordance with the trust agreement? Which section of the trust agreement stipulates the conditions in which a power holder may remove or replace a Trustee?

- Which country has jurisdiction over the trust? Where is the trust administered?

- In which country or region is the Trustee or Trust Company regulated?

- Who is the primary contact person for the trust?