專業叢書

Estate Planning by U.S. Trust 美國報稅與海外財產揭露(英文部分)

Chapter 1 ─ The Meaning of Inheritance

Section 2: The Rise and Fall of Familial Wealth: The Need to Act

1. Why do intergenerational wealth transfers fail?

The following is an excerpt from Chinese folklore: Families that are able to pass on their core values can remain wealthy for more than ten generations. Families with ambition and perseverance can grow their wealth indefinitely but the wealth will not last longer than in those families that understand the importance their core values and principles. Families who are indecisive and irresponsible will quickly cease to pass on their wealth. Heirs who solely rely on their parents will inevitably lose their family’s wealth before the third generation.

Mencius, a Chinese Confucian philosopher, once said, “A man’s wealth cannot be preserved for more than five generations.” The word Ze (澤) means “rain and dew”, but also symbolizes the fruits of a family’s business; the word Zhan (斬) means “cut off”, but also symbolizes the decay of a family’s business.

“The motivation to achieve success dwindles as the sense of entitlement rises through each generation. If future generations do not find their own field of expertise, wealth generated by prior generations will only allow them to indulge in poor life choices.” Passing down a family’s principles is thus significantly more important than passing down a family’s fortune.

The author’s grandfather was born in the Qing Dynasty. He grew up and studied during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan and passed away after World War II. He dabbled in philosophy and proposed family wealth succession theories over 100 years ago. He theorized that if even one generation fails to preserve wealth, the transition of wealth will be shortened significantly.

Over the past three decades, the author has helped many families with succession planning and come to realize the various reasons why familial wealth succession generally fails.

The prophesy of the three generations is as follows:

A successful Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “First Generation” in Asia, most often marks the peak of a family’s wealth and economic status. The “classic” first generation refuses to live in luxury but prefers a modest lifestyle, driving a single car for many years and flying in economy. Born with a passion to understand their surroundings, they seek to singlehandedly make something of themselves and are able to grasp opportunities. Their modest upbringing, exhaustive diligence and multifaceted talents allow them to generate a rather significant sum of wealth in their lifetimes.

The children of the Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “Second Generation” in Asia, often focus on growing and preserving the family’s wealth, accomplishments and status. As they grow up, they learn from the Wealth Creators directly and are mostly able to continue familial ethics and rituals. Since most of the second generation realize that they are not as gifted as their predecessors, they tone down their lifestyles around their ascendants but live a moderately comfortable life nevertheless.

The children of the second generation, commonly referred to as the “Third Generation” in Asia, often remove themselves from the preservation of wealth altogether. The third generation often grow up in an environment ill fitted for learning the difficult task of preserving the family’s wealth and status. Since the minute they were born, they are endowed a luxurious lifestyle without a care in the world. This breeds shortsightedness, leading many in the third generation to believe that money can buy happiness.

Studies also show that passing wealth on for more than three generations is indeed a challenge for many families.

(1) A survey conducted by U.S. Trust, a subsidiary of Bank of America, found that 64% of wealth creators disclosed little of their wealth to their children and 78% feel that the next generation is not financially responsible enough to handle assets they are given.

(2) A separate study conducted by Merrill Lynch found that only 15% and 2% of families in East Asia successfully transition their family businesses to the second and third generations, respectively.

(3) In 2017, CNBC reported that, “one-third of Asia’s wealth may change hands in the next five years.” It reported that many families will see their wealth reduced due to familial disputes and transition taxes.

2. Types of Wealth Creators and the problem they face

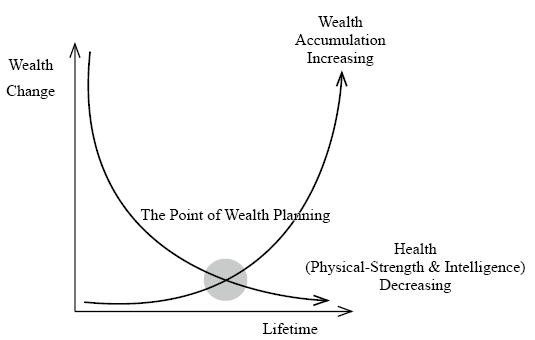

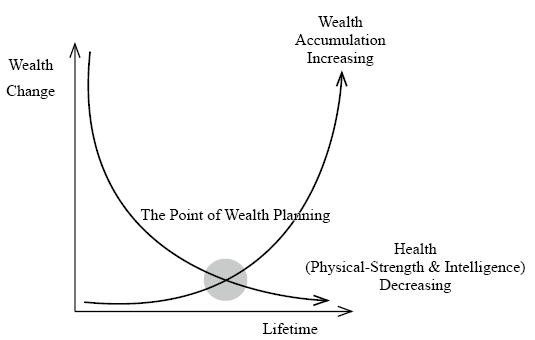

Wealth Creators often work their entire lives dedicated to their profession. By starting early and integrating their succession plan with their businesses, they can expand upon their creations and build a lasting legacy, one that incorporates their family, their employees and society at large. Wealth Creators who fail to invest adequate time and energies in creating and protecting their legacies often leave behind lasting familial disputes, shareholder disagreements, employee distress and unnecessary conflict various judicial and administrative organizations. As a Wealth Creator, you must ask yourself, “Who is my successor?” After all, the first step in familial succession is choosing a viable successor.

After meeting with many Wealth Creators, the author has come to the conclusion that the main reason they fail to act is because they fear that their actions would lead to succession inequality. Thus, they shy away from discussing or planning their legacies. Generally, Wealth Creators can be categorized into the four following categories:

If you are a potential successor and become aware of your family’s assets, you may want to consider which category your ascendants belong under. This could potentially determine your next course of action. After thinking about your ascendants, you should also think about your role in the family. Generally, the second generation falls in one of the following categories:

(1) The second generation often have less pronounced Asian values. This is especially true of descendants who have lived abroad for many years or those who started families outside of Asia. Although they are of Asian descent, they identify more closely with Western values and focus more on realizing personal goals rather than strengthening the family business and thinking on behalf of the greater family at large.

(2) The second generation may not need financial support from their families: they are often efficient workers, enjoying high socioeconomic statuses wherever they settle. Many may play an active role in their communities. Some second generation are even financially independent and live comfortably even without their families’ assets. They may not want or need wealth created by their ascendants and the responsibilities that come with that wealth. For this category of second generation, their family’s various businesses and assets could actually end up becoming a sizable burden rather than an asset.

(3) Some second generation may lack the foresight or strategic direction necessary to continue the family business. Familial disputes may arise if the second generation refuses to make decisions regarding the family business. Relationships with longstanding employees in the family business may also falter as a result of inaction or poor decision-making. The author believes that the second generation should hold themselves responsible for their family’s business, whether they choose to manage it themselves or have others manage it on their behaves.

While many Wealth Creators and their descendants want to transition their family businesses and other assets to the next generation, four major points of contention generally arise when they begin to consider succession:

(1) Transfer Costs

In many jurisdictions, there is a significant cost related to the transfer of assets from one generation to the next, especially if the assets transferred are sizable. For example, the highest intergenerational transfer tax rates in Taiwan, the United States and Japan can run as high as 20%, 40%3 and 55%, respectively. As it stands, according to various online sources, the transfer tax rate in China is slated to be implemented at 50%.

3 Excludes U.S. generation-skipping taxes (GST).(此處40%不含美國隔代移轉稅)。

(2) Succession Disputes

Succession disputes may arise as a result of a number of factors, often exacerbated by a lack of prior planning by the Wealth Creator before he or she is incapacitated. Typically, the second generation either dispute ① the assets they are entitled to or ② the various business responsibilities delegated to them.

When the first generation fails to create a comprehensive succession plan, the family business and other familial assets are often hurriedly passed on. The second generation, often unaware of the situation prior to the Wealth Creator’s death or incapacity, may be woefully unprepared to singlehandedly handle familial businesses and affairs.

The use of nominal holders of assets, commonly referred to as “nominees,” a common tactic in Asia, may only serve to further complicate the situation. If a nominee passes away or become incapacitated, the transfer of assets to the second generation may become fraught with additional expenses and challenges. It is common that disputes (either in or out of court) with nominees significantly reduce the assets passed to the second generation.

(3) Debt Disputes

While debt is instrumental in many businesses’ growth, it can also be a source of disputes during a family’s wealth transition from one generation to the next. With a larger scale comes larger profits; however, disputes regarding the legitimate owner(s) of a family’s assets and liabilities may be exacerbated by the existence of significant outstanding debts. A family’s equity can quickly be reduced if the family lacks the ability to pay either the interest expense of debt or the balloon payment upon maturity.

(4) Differences in Familial Focus and Values

The second generation often focus on different aspects of life, when compared to the Wealth Creators. While the Wealth Creator may be concerned about his or her profits and legacy, his or her descendants can focus on their time and energies on pursuing matters of interest to them rather than the profitability of the family’s businesses. Thus, without adequate and timely communication, familial values and virtues will likely not stand the test of time.

The following is an excerpt from Chinese folklore: Families that are able to pass on their core values can remain wealthy for more than ten generations. Families with ambition and perseverance can grow their wealth indefinitely but the wealth will not last longer than in those families that understand the importance their core values and principles. Families who are indecisive and irresponsible will quickly cease to pass on their wealth. Heirs who solely rely on their parents will inevitably lose their family’s wealth before the third generation.

Mencius, a Chinese Confucian philosopher, once said, “A man’s wealth cannot be preserved for more than five generations.” The word Ze (澤) means “rain and dew”, but also symbolizes the fruits of a family’s business; the word Zhan (斬) means “cut off”, but also symbolizes the decay of a family’s business.

“The motivation to achieve success dwindles as the sense of entitlement rises through each generation. If future generations do not find their own field of expertise, wealth generated by prior generations will only allow them to indulge in poor life choices.” Passing down a family’s principles is thus significantly more important than passing down a family’s fortune.

The author’s grandfather was born in the Qing Dynasty. He grew up and studied during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan and passed away after World War II. He dabbled in philosophy and proposed family wealth succession theories over 100 years ago. He theorized that if even one generation fails to preserve wealth, the transition of wealth will be shortened significantly.

Over the past three decades, the author has helped many families with succession planning and come to realize the various reasons why familial wealth succession generally fails.

The prophesy of the three generations is as follows:

A successful Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “First Generation” in Asia, most often marks the peak of a family’s wealth and economic status. The “classic” first generation refuses to live in luxury but prefers a modest lifestyle, driving a single car for many years and flying in economy. Born with a passion to understand their surroundings, they seek to singlehandedly make something of themselves and are able to grasp opportunities. Their modest upbringing, exhaustive diligence and multifaceted talents allow them to generate a rather significant sum of wealth in their lifetimes.

The children of the Wealth Creator, commonly referred to as the “Second Generation” in Asia, often focus on growing and preserving the family’s wealth, accomplishments and status. As they grow up, they learn from the Wealth Creators directly and are mostly able to continue familial ethics and rituals. Since most of the second generation realize that they are not as gifted as their predecessors, they tone down their lifestyles around their ascendants but live a moderately comfortable life nevertheless.

The children of the second generation, commonly referred to as the “Third Generation” in Asia, often remove themselves from the preservation of wealth altogether. The third generation often grow up in an environment ill fitted for learning the difficult task of preserving the family’s wealth and status. Since the minute they were born, they are endowed a luxurious lifestyle without a care in the world. This breeds shortsightedness, leading many in the third generation to believe that money can buy happiness.

Studies also show that passing wealth on for more than three generations is indeed a challenge for many families.

(1) A survey conducted by U.S. Trust, a subsidiary of Bank of America, found that 64% of wealth creators disclosed little of their wealth to their children and 78% feel that the next generation is not financially responsible enough to handle assets they are given.

(2) A separate study conducted by Merrill Lynch found that only 15% and 2% of families in East Asia successfully transition their family businesses to the second and third generations, respectively.

(3) In 2017, CNBC reported that, “one-third of Asia’s wealth may change hands in the next five years.” It reported that many families will see their wealth reduced due to familial disputes and transition taxes.

2. Types of Wealth Creators and the problem they face

Wealth Creators often work their entire lives dedicated to their profession. By starting early and integrating their succession plan with their businesses, they can expand upon their creations and build a lasting legacy, one that incorporates their family, their employees and society at large. Wealth Creators who fail to invest adequate time and energies in creating and protecting their legacies often leave behind lasting familial disputes, shareholder disagreements, employee distress and unnecessary conflict various judicial and administrative organizations. As a Wealth Creator, you must ask yourself, “Who is my successor?” After all, the first step in familial succession is choosing a viable successor.

After meeting with many Wealth Creators, the author has come to the conclusion that the main reason they fail to act is because they fear that their actions would lead to succession inequality. Thus, they shy away from discussing or planning their legacies. Generally, Wealth Creators can be categorized into the four following categories:

- Type 1: The Staunch Believer thinks that their children and grandchildren should and will take care of themselves. They are steadfast in their beliefs and willingly choose to disregard potential disputes that may arise after their death.

- Type 2:The Procrastinator believes that their legacy is still a distant concern and fails to plan for their legacy in time.

- Type 3: The Overthinker fails to act due to their inability to make a coherent decision about his or her legacy. As the years pass by, they fail to make any progress in planning for their successors. They often regard potential successors, some as old as 60 years old, as children incapable of handling their family’s business affairs. Often times, Overthinkers also leave a multitude of different assets in a disarray and do not wish to plan the eventual transition of their wealth.

- Type 4:

If you are a potential successor and become aware of your family’s assets, you may want to consider which category your ascendants belong under. This could potentially determine your next course of action. After thinking about your ascendants, you should also think about your role in the family. Generally, the second generation falls in one of the following categories:

(1) The second generation often have less pronounced Asian values. This is especially true of descendants who have lived abroad for many years or those who started families outside of Asia. Although they are of Asian descent, they identify more closely with Western values and focus more on realizing personal goals rather than strengthening the family business and thinking on behalf of the greater family at large.

(2) The second generation may not need financial support from their families: they are often efficient workers, enjoying high socioeconomic statuses wherever they settle. Many may play an active role in their communities. Some second generation are even financially independent and live comfortably even without their families’ assets. They may not want or need wealth created by their ascendants and the responsibilities that come with that wealth. For this category of second generation, their family’s various businesses and assets could actually end up becoming a sizable burden rather than an asset.

(3) Some second generation may lack the foresight or strategic direction necessary to continue the family business. Familial disputes may arise if the second generation refuses to make decisions regarding the family business. Relationships with longstanding employees in the family business may also falter as a result of inaction or poor decision-making. The author believes that the second generation should hold themselves responsible for their family’s business, whether they choose to manage it themselves or have others manage it on their behaves.

While many Wealth Creators and their descendants want to transition their family businesses and other assets to the next generation, four major points of contention generally arise when they begin to consider succession:

(1) Transfer Costs

In many jurisdictions, there is a significant cost related to the transfer of assets from one generation to the next, especially if the assets transferred are sizable. For example, the highest intergenerational transfer tax rates in Taiwan, the United States and Japan can run as high as 20%, 40%3 and 55%, respectively. As it stands, according to various online sources, the transfer tax rate in China is slated to be implemented at 50%.

3 Excludes U.S. generation-skipping taxes (GST).(此處40%不含美國隔代移轉稅)。

(2) Succession Disputes

Succession disputes may arise as a result of a number of factors, often exacerbated by a lack of prior planning by the Wealth Creator before he or she is incapacitated. Typically, the second generation either dispute ① the assets they are entitled to or ② the various business responsibilities delegated to them.

When the first generation fails to create a comprehensive succession plan, the family business and other familial assets are often hurriedly passed on. The second generation, often unaware of the situation prior to the Wealth Creator’s death or incapacity, may be woefully unprepared to singlehandedly handle familial businesses and affairs.

The use of nominal holders of assets, commonly referred to as “nominees,” a common tactic in Asia, may only serve to further complicate the situation. If a nominee passes away or become incapacitated, the transfer of assets to the second generation may become fraught with additional expenses and challenges. It is common that disputes (either in or out of court) with nominees significantly reduce the assets passed to the second generation.

(3) Debt Disputes

While debt is instrumental in many businesses’ growth, it can also be a source of disputes during a family’s wealth transition from one generation to the next. With a larger scale comes larger profits; however, disputes regarding the legitimate owner(s) of a family’s assets and liabilities may be exacerbated by the existence of significant outstanding debts. A family’s equity can quickly be reduced if the family lacks the ability to pay either the interest expense of debt or the balloon payment upon maturity.

(4) Differences in Familial Focus and Values

The second generation often focus on different aspects of life, when compared to the Wealth Creators. While the Wealth Creator may be concerned about his or her profits and legacy, his or her descendants can focus on their time and energies on pursuing matters of interest to them rather than the profitability of the family’s businesses. Thus, without adequate and timely communication, familial values and virtues will likely not stand the test of time.